There’s an important point I try to make when I’m out in public talking about the 2014 Colorado River Delta environmental pulse flow: the amount of water used and the size of the landscape that got wet, compared to the once-vast delta, is tiny.

beaver dam at Laguna CILA site, March 27, 2014, by John Fleck

I get excited about the pulse flow, when water managers on both sides of the US-Mexico border in the spring of 2014 released water from Morelos Dam into the usually-dry delta. For those of us who were there, it was a life-changing experience. But at a bit more than 100,000 acre feet of water, it was less than 1 percent of the water that once flowed every year into the delta before we diverted the Colorado River’s water upstream for our farms and cities.

But in modern environmental habitat creation/restoration efforts, what happened then and in the two years since illustrates something that’s increasingly coming to dominate institutional discussions of returning water to the environment in the West’s arid landscape. Absent abandoning all those farms and cities – which we’re not going to do – we’re not going to return the rivers to the way they were. But the delta pulse flow experiment shows that even a small amount of water – “in the right spot and at the right time”, in the words of the University of Arizona’s Karl Flessa, one of the leaders of the pulse flow science team – can yield big results.

That’s the key message found in the International Boundary and Water Commission’s latest follow-up report, completed earlier this year and just now posted publicly (pdf). If you don’t want to wade through the full technical details, Mari Jensen at the University of Arizona wrote a nice summary of the findings:

Birdlife responded to the post-flood burgeoning of vegetation, and bird diversity is still higher than before, the monitoring team reports. Migratory waterbirds, nesting waterbirds and nesting riparian birds all increased in abundance.

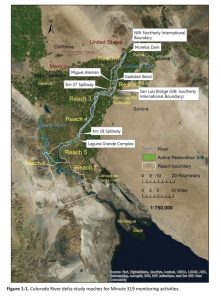

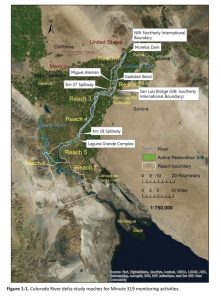

Colorado River delta pulse flow map, courtesy IBWC

One of the important things I think we seem to be learning in this experiment is that it may be more efficient, in terms of environmental benefit per unit water used, to move the water through irrigation systems and deliver it to targeted spots in the flood plain that way rather than running it straight down the river channel. One of the most important habitat restoration areas is the Laguna Grande restoration site, near the bottom in the map on the right. You can get more water there if you run it through the irrigation canals rather than down the main river channel.

The flow down the main channel was too small to do much of the natural “scouring” that a real flowing river does. That scouring is essential for preparing habitat for the germination of riparian vegetation. So if you only have a little bit of water to work with, manual human scouring with heavy equipment to prepare habitat for the water’s arrival is going to be important. Key lesson.

These features of the experiment – delivery of water through the irrigation system and manual preparation of the land for the water’s arrival – lead to all sorts of interesting questions about what counts as “natural”, which is a conversation we need to have. But if your goal is measurable habitat improvement, birds and such, that seems to be the best way to do it.

I spent a bunch of time on the pulse flow in my new book, Water is for Fighting Over: and Other Myths about Water in the West, because it was a storyteller’s dream:

Scientific data is scant, but locals say beavers were nearly completely gone from the region during the dry times that came with the closure of Glen Canyon Dam and the diversion of the river’s entire flow. But on the few occasions that the delta flooded, the beavers would reappear, perhaps following the flow down from refuges upstream.

And so it was again, in the spring of 2014. A small flow of excess agricultural water flowed past willows through a human-built environmental restoration site. As soon as the water arrived, delivered through irrigation canals in an early phase of the river restoration efforts, beavers materialized out of the ecological mists, damming the little channel. They had found their way back.

I’ve worried that, in the excitement of my personal experience of it, I was overselling the pulse flow. But the data show benefits lingering, and they also show this central lesson – if we think carefully about how to deploy a bit of our scarce water for the environment, a little bit can go a long way.

Update: Audubon also has a nice writeup on the results.