Aspens in the Sandias, putting on a show.

Tree Spring Trail FTW.

Update: Data here is from USDA, the “USGS” in the graphs is a typo in the code I used to generate them, which I’m too lazy to fix.

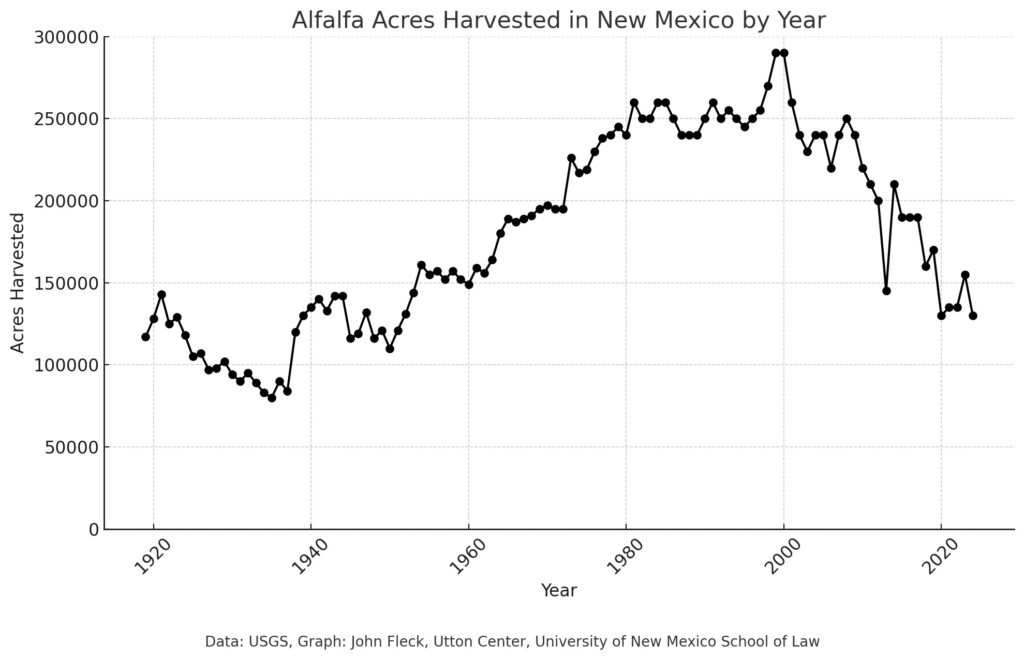

New Mexico alfalfa acreage is the lowest it’s been since the 1950s.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2024 estimate of alfalfa acreage in New Mexico, 130,000 acres, is the lowest it’s been since the 1950s. Acreage is down 55 percent since the peak at the turn of the century.

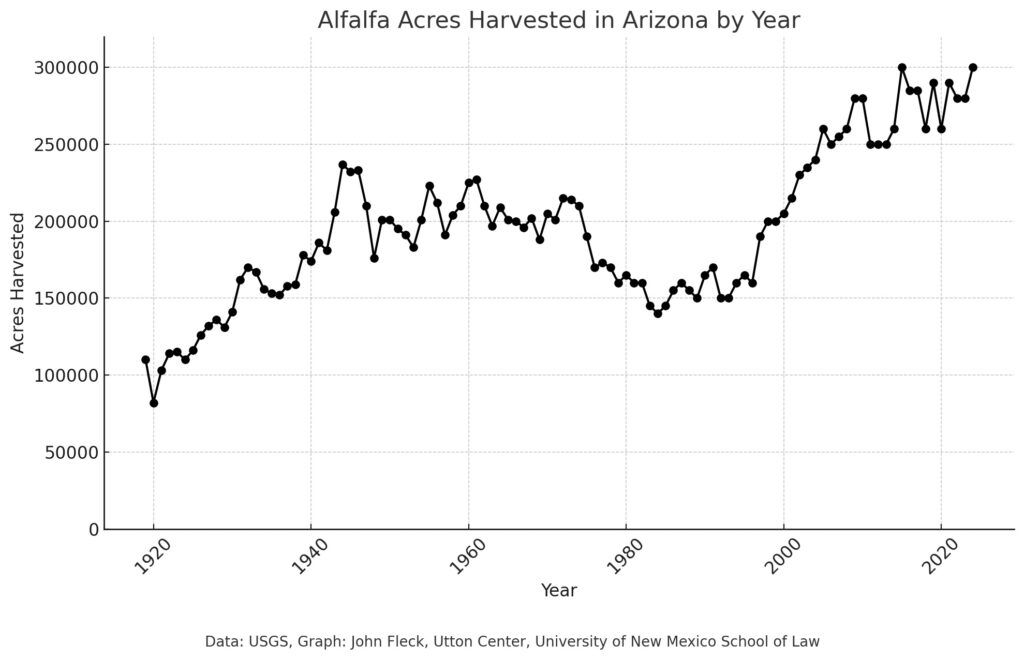

Here’s Arizona:

Different story for Arizona.

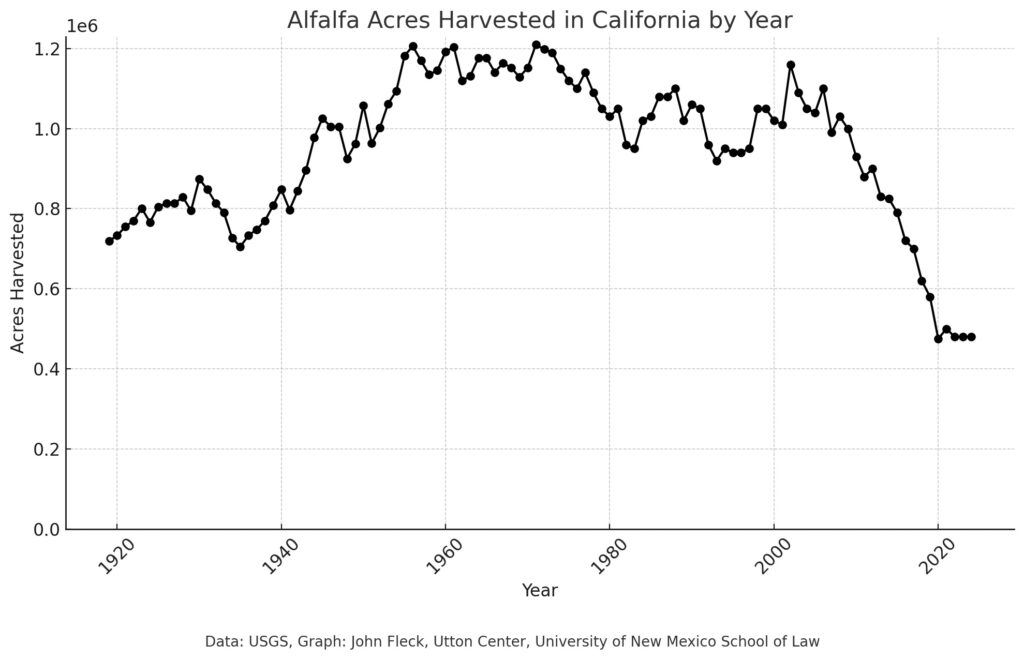

California:

California, growing less alfalfa

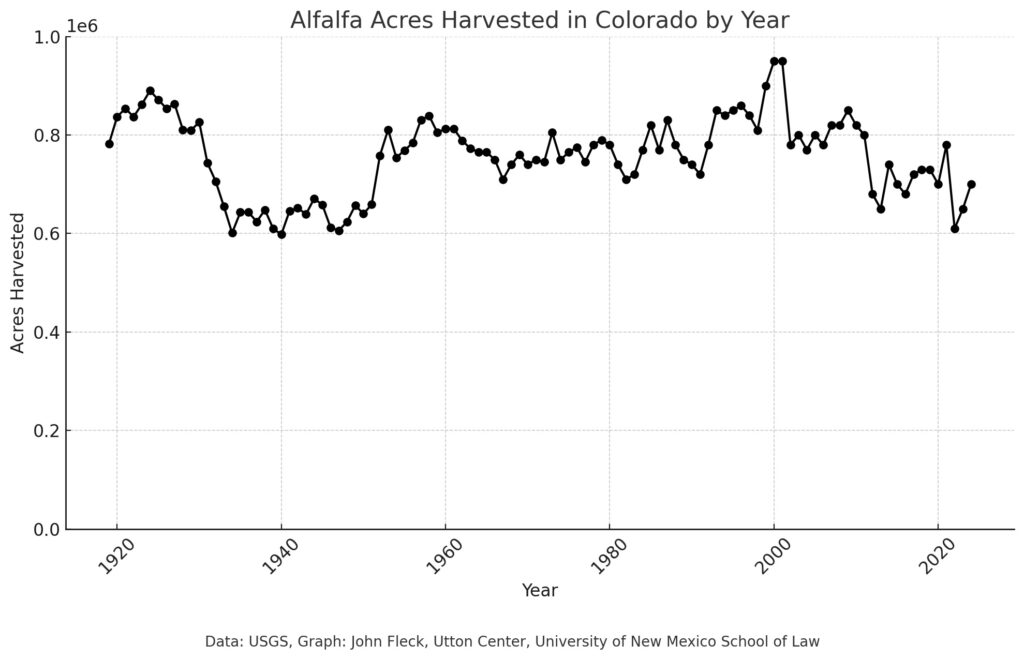

Colorado

The Arizona Department of Water Resources has published a thoughtful and also delightfully testy response to Enduring Solutions on the Colorado River, the white paper Kathryn Sorensen et al. (I’m one of the et alias) published in August.

First a reminder of our core premise:

As we work to reduce water use on the post-2026 Colorado River, two paths lie open before us.

One is to incentivize conservation by giving water users the chance to bank saved water for later use. Known most commonly as Intentionally Created Surplus (ICS), and more broadly in a series of increasingly creative implementations as “Assigned Water,” this creates short term savings. But in the long run, the approach entitles the users to take the water back out of the bank.

The other involves permanent reductions – “System Water.” Water use is reduced for the benefit of the Colorado River as a whole.

Investment in Assigned Water, attractive to water managers because of the allure that they can get their water back, has crowded out investment in the more durable System Water reductions that will be needed to bring the Colorado River into balance.

ADWR agrees with a lot of what we said (yay!):

ADWR agrees wholeheartedly with the general premise that System Water is preferable to any category of Assigned Water. Increased volumes of System Water will improve outcomes for water users across the entire Basin, as well as the environment. ADWR also agrees with the need to divorce decisions regarding system operations from any Assigned Water stored in the system.

ADWR takes issue with a lot of what we said (also yay!), and also was kinda mean – “Baseless Accusations and Little Substance” (also yay! because we need to be having these frank discussions – I worry being too polite isn’t helping right now).

I’m delighted this discussion is underway in a public forum. Go read the whole thing.

Water resources must be governed before they can be managed, and the crafting of governance institutions is an ongoing challenge of the human condition. Institutional artisanship requires the availability of tools for institutional design and creation, and a reflective understanding of the use of those tools. Yet neither the tools nor the understanding exist in their entirety before institutional artisans attempt their craft: the tools at hand must be adapted to new purposes, and skill in their use must be learned along the way. Errors are inevitable, but successes are possible.

Blomquist, William. “Crafting water constitutions in California.” The practice of constitutional development: Vincent Ostrom’s quest to understand human affairs (2006): 99-134.

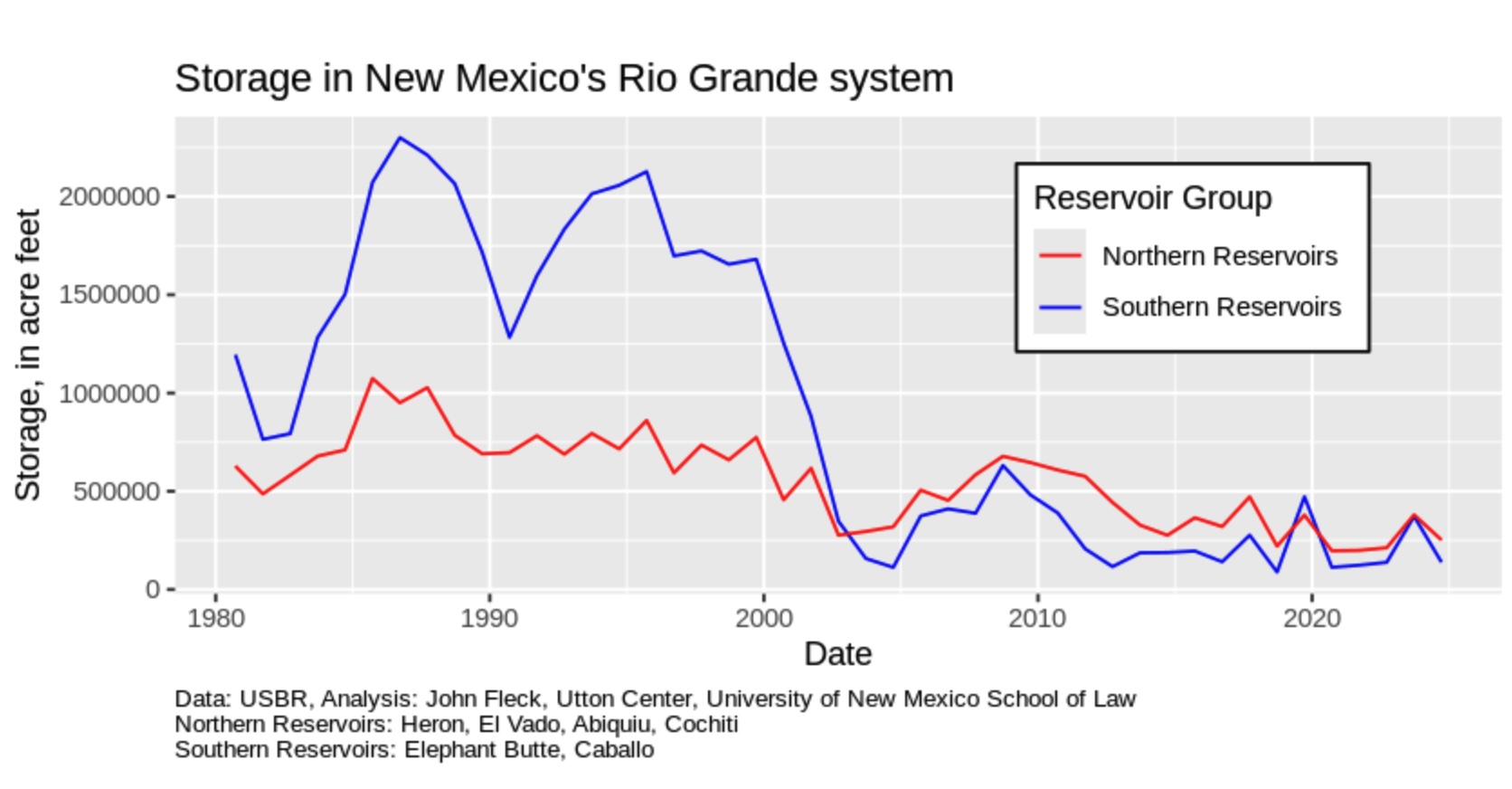

Bouncing along the bottom.

Sept. 30 marks the end of the “water year,” an accounting milestone that gives us an opportunity to take stock.

The change in total water storage year-over-year is one way to do this, to help understand if we took more water out of the reservoirs than the climate put in. The graph above is actually based on Sept. 20 year-over-year (the Reclamation data updates lag a bit), but it’s enough to give us a feel for two things.

First, we’ve seen no real reversal of the long term pattern – a huge reduction in storage in the early 21st century, and then basically dragged the bottom of the reservoirs ever since.

Second, on a shorter one- or two-year time scale, total storage is down ~350,000 acre feet at the end of water year 2024 compared to the end of 2023. Over a two-year time scale, we basically burned through the bonus water from a wet 2023 and are back where we were at the end of 2022.

Rio Grande flow this year at Otowi in north-central New Mexico has been 63 percent of the period of record mean, going back to the late 1800s.

When John Oliver used some of my work in a piece about water a couple of years ago, I spent a long time with one of the show’s producers as they developed it. Then, right before it aired, I spent more time in an intense round of fact-checking.

It was marvelous. They were fact-checking the jokes.

In a recent interview, Oliver explained the process:

But in terms of the responsibility of journalism, we do have intense fact-checking because we want it to be right. Those big stories are aggregations of incredible journalism. So it cannot function without journalism. Now, we recheck it to make sure it’s accurate or that it hasn’t changed, but we’re building this to make jokes. It’s just we want the foundations to be solid or those jokes fall apart. Those jokes have no structural integrity if the facts underneath them are bullshit.

Cracked mud – memories of Lake Mead’s low stand. Art and photo by L. Heineman.

Two years ago, when the level of Lake Mead was hovering near elevation 1,040, my artist wife Lissa Heineman and I drove out over UNM’s fall break to see it for ourselves.

Out beyond the old Boulder Harbor, we walked a half mile across mud flats to get to the water. I could look out across the water to see the elbow of the old Southern Nevada Water Authority intake, above the water line. I was gut-punched by the visceral reality.

Lake Mead in the 1,040s, October 2022.

On the walk back to the car, Lissa carefully picked up some pieces of cracked mud. Her art has always been wrapped up in the conceptual properties of her materials. So she carefully packed up the cracked mud in a box and took it home. It’s been sitting in her studio ever since, and last month she tried firing some of it atop some small ceramic plates in her kiln.

It worked, and she gave me the results to give to my Lower Basin/Lake Mead friends. The texture of the mud, with ripples across the sandy and muddy reservoir bottom, captures a moment in history I hope we never repeat.

So last week, with the Colorado River brain trust in Santa Fe for the Water Education Foundation’s always-fascinating Colorado River symposium, I drove up to see folks and stuck a couple of Lissa’s pieces in my backpack.

I shared them with a message: That was scary. Let’s not go back there again. Please don’t fuck this up.

I’ve got a lot going on – revisions to the new book, teaching my fall semester graduate-level water resources class, nervously eyeing the levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead, and the gridlock in Colorado River negotiations. So when my brain suggested listening to Rubber Soul Friday night, I was resistant. But we’ve been together for a long time, and I trust my brain’s judgment. So Rubber Soul it was.

What a great album.

This post is lengthy and rambly, so for those who are annoyed by my discursive side trips and just here for the Colorado River stuff, I’ve added anchors to the key material:

When Eric Kuhn and I set out to write Science Be Dammed, the project arose in part out of a mutual fascination with E.C. LaRue, the early 20th century hydrologist who first tried to map out the supply of water, and possible uses of it, across the entire Colorado River Basin. The thing that first drew me to LaRue, long before I knew Eric, was the fundamental innovation of what LaRue and the others working at the time on similar projects were doing. No one had ever tried to envision managing a continental-sized river at the full basin scale.

Rubber Soul

In an entirely different context and framework, it’s a theme Bob Berrens and I take up in our new book Ribbons of Green, about the making of a city.

The first time I remember thinking hard about this was when Lissa, my sister Lisa, and I saw the Hermitage exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1986. It was a magnificent sweep of early modern painting that had been collected by rich Russians before the revolution. I remember rounding a corner and being gobsmacked by a big Picasso canvas, Three Women, one of the first few cubist paintings that he and George Braque had been making in Paris in 1907-08. Lissa, who understood the history, took me back through the rest of the exhibit to see the roots – the impressionists breaking one way, Matisse another, and Cezanne sweeping them all away with the beginnings of the deconstruction of the picture plane that led to Braque and Picasso.

My own father had been deeply influence by the reverberations of that work, and I had always seen it in Dad’s work, but it wasn’t until Lissa held my hand and walked me through the history that I began thinking about pathways. How does this happen? Once I saw, read, and learned about it once, I became hungry for examples. My intellectual life is now littered with them. I have long since soured on Picasso himself (what an asshole!), but the genre of intellectual journey continues to fascinate.

The most interesting books I’ve read in recent years all document this – Patti Smith’s Just Kids, about the birth of punk and her invention of Patti Smith; Amartya Sen’s memoir Home in the World; Henry Threadgill’s Easily Slip Into Another World (I still can’t grasp the music, but his story of innovation is a joy); Stanley Crouch’s biography of early Charlie Parker, Kansas City Lightning. In each case (three memoirs, one not), the innovation is rooted in a deep understanding of the past and foundations, and then the ability to see, out of that, something entirely new. And all four books are ripping good reads.

I love playing this game with the Beatles, because thanks to streaming services it is possible to dive in and listen to them learning on the fly, to watch the way the bar band Beatles learned how audiences responded to the old things and began envisioning something new.

This is metaphor.

As we near the Sept. 30 end of the water year, Lake Mead is at elevation 1,064 feet above sea level, twenty feet above where it was when Lissa picked up the cracked mud two years ago.

In 2021-22, it took one year to drop from the 1,060s to the 1,040s. Could this happen again?

The short answer is probably not in a single year, because of a couple of things that have changed since then. But in two years? Yup. Lissa and I could have a chance to collect more 1,040s cracked mud.

The first thing that has changed since 2022 is the release from Lake Powell. In 2022 the Basin was in the midst of its hair-on-fire crisis management because of fears of Powell dropping dangerously low, so the Powell release that year was just 7 million acre feet. This year, it’s 7.48 million acre feet. So more water coming into Mead.

Things are also better on the outflow side. In 2022, the three Lower Basin States used 6.66 million acre feet. This year, the latest forecast number is 6.09 million acre feet.

Between the higher inflows and lower use, the latest midpoint forecast has Mead ending next year at 1,059 feet above sea level, with Reclamation’s most pessimistic model runs (the “minimum probable”) at ~1,054. But the min probable clearly shows risk out at the edge of what our headlights can illuminate right now, of dropping back into the 1,040s again by the summer of 2026.

The “game of chicken” is a game theory classic. It involves a conflict which, in the classic storytelling version, involves two drivers headed toward one another on a collision course. We’ll call them “U” and “L”. Each has the option to swerve or stay on course. The best outcome for each driver is for the other to swerve and lose face (water), while the driver who stays the course demonstrates dominance (keeps its water). But if neither swerves, we end up with a catastrophic collision. In the game theory matrix, it looks like this, with the payoffs for each:

| Driver U Swerves | Driver U Stays | |

| Driver L Swerves | (0,0) | (-1,1) |

| Driver L Stays | (1,-1) | (-10,-10) |

I’m obviously talking about the Upper Basin and the Lower Basin here, which are at impasse over the Lower Basin’s proposal to cut deeply up to a point (1.5-ish million acre feet total) and, if any deeper cuts are needed, to share them among the two basins.

The Upper Basin’s counter is basically “no.” If deeper cuts are needed, the Lower Basin should make them.

The payoff matrix, though, is a lot more complicated than my toy example above. First, both sides can gamble on good hydrology, which could avert the crash. So even if the impasse remains, the collision is not a sure thing. (In this regard, it’ll be interesting to see how the players’ strategies shift if we have a really bad winter.)

The second is the nature of the collision itself. No one knows quite what it will look like.

In the classic chicken game, both drivers know about the crash that happens if neither swerves. But part of the risk calculation we all have to live with right now is the uncertainty about what happens if the Upper and Lower Basin states can’t come to an agreement. We also have a situation where the nature of the game is changing over time.

Walking down a Santa Fe sidewalk Wednesday evening after dinner, one of my Colorado River friends observed that both sides seem to think that, if the collision comes, they have a winning legal argument.

If you think that, your understanding of what happens in the bottom right quadrant of the matrix, the crash scenario, is very different.

The Upper Basin seems to have convinced itself, at least based on public pronouncements, that it has a winning legal argument in terms of its obligation, or lack thereof, to send water downstream past Lee Ferry. This seems dangerous to me given my understanding of the history and the law, but it doesn’t matter what I think. The Upper Basin seems happy to keep hammering down the road.

Once deliveries past Lee Ferry drop below one of the “tripwire” triggers (82.5maf / ten years or 75/10), the Lower Basin states have nothing to lose by suing. And when that happens, my community’s water supply is at risk if my basin’s lawyers aren’t right.

Crash!

A few years back Kaveh Madhani and Bora Ristic wrote a paper working out the details of a game theory example that seems to fit what we’re currently seeing in the Lower Basin’s proposal to “own” the 1.5 million acre feet of structure deficit, and to try to negotiate some sort of sharing arrangement if the cuts need to go deeper. This would appear to be what Ristic and Madhani describe as “strategic loss.”

Without foresight into game changes over time, players are blind to the fact that they are in a game of chicken. We model agents with foresight by interconnecting games across time and show how this creates opportunities for “strategic loss” early on, allowing players with foresight to reduce total costs. High future costs can thus be avoided with foresight if the rising costs of inaction are made apparent.

Which seems to model what the Lower Basin has done.

I would prefer to live in the upper left quadrant of the chicken game matrix, where both sides compromise. My values: mindful shared reductions across the basin can leave us all with healthy, thriving communities. I wrote a whole book about this path. But one of my smart friends pointed out something that is a reasonable hypothesis: The model I laid out in that book, written a decade ago, was sufficient on a river that shrinks some, but seems to be failing on a river that has shrunk a lot.

Risti? and Madhani seem to be suggesting a game theoretic path that could get us back on track.

Thanks so much to Inkstain’s supporters. You can join them here.

Billets, used in glass casting

I tagged along Friday with my glass artist kiddo Nora on a trip to Bullseye Glass, an art supply store in Santa Fe.

Nora makes stuff out of glass for their jewelry business, and needed to stock up. After a busy week, I needed to not work, and have fun instead. We went to our favorite Santa Fe lunch stop, and then art supply store!

I’ve been going to art supply stores my whole life – with Dad when I was a kid, with wife Lissa, and now with Nora. I love them. They are so full of promise, of raw materials awaiting the touch of the artist, the mixing and remaking and shaping, of reifying, of making real.

This was my first time at the glass store. Glass is especially alluring.

Between mid-April and early July 2024, reservoir storage in the Colorado River basin increased by 2.45 million acre feet (af). Now we are in the nine-month period of progressive decline as reservoir storage supports consumptive uses and losses throughout the basin until the 2025 spring snowmelt season begins. As of 1 September 2024 basin reservoir storage was 28.9 million af, and the combined storage in Lake Mead and Lake Powell was 18.0 million af. Those amounts are similar to conditions from spring 2021 when media outlets began reporting on the emergence of a water crisis. That crisis continues.

It is useful to monitor changes in basin reservoir storage because it is the “bank account” from which we can make withdrawals during dry years. Basin water managers have little control over each year’s watershed runoff, but they have a continuing ability to reduce water consumption.

Basin water managers have a long way to go to replenish reservoir storage to amounts that ensure a secure and reliable water supply. Today’s water in the basin’s reservoirs is slightly more than a two-year supply, based on the average rate of water consumption and losses[1] in the basin. It remains in a precarious state should a string of very dry years occur, as was the case between 2002 and 2004 and between 2020 and 2022.

Although the ultimate cause of the ongoing crisis in water supply is a declining watershed runoff associated with a warming climate, the proximate cause is the inability to reduce consumptive uses to match the declining supply[2]. John Fleck summarized recent progress in reducing Lower Basin water use[3]— that is the kind of progress needed throughout the basin.

Figure 1 is a reminder that present reservoir storage remains low in relation to conditions throughout the 21st century. Today, 62% of total basin storage is in Lake Mead and Lake Powell, 30% of storage is in reservoirs upstream from Lake Powell, and 8% of storage is in Lake Mohave and Lake Havasu. Storage in reservoirs upstream from Lake Powell increases during each year’s snowmelt season, and subsequently decreases to sustain consumptive uses. Storage in Lake Mohave and Lake Havasu change little. The big changes in the basin are mostly due to changes in storage in Lake Mead and Lake Powell.

Figure 1. Graph showing reservoir storage in the Colorado River basin between 1 January 1999 and 31 August 2024.

The water supply in Lake Mead and Lake Powell, as well as Lake Mohave and Lake Havasu, supports water use in the Lower Basin and in Mexico. Lake Powell is downstream from virtually all Upper Basin water use. Essentially, Lake Powell and Lake Mead are one reservoir, separated into two parts by the Grand Canyon. Nevertheless, Lake Mead and Lake Powell are operated differently, as is evident in Figure 2. In spring and early summer, snowmelt runoff is captured in Lake Powell, and storage increases there even though storage at the same time decreases in Lake Mead in some years. Once the snowmelt season ends, water is transferred to Lake Mead, and Lake Powell storage slowly declines. Figure 2 demonstrates that changes in water storage in Lake Mead occur over longer cycles than do the annual cycles of storage change that occur in Lake Powell. Because of the different operating rules of the two reservoirs, basin water storage conditions are better reflected by the combined storage contents of the two reservoirs rather than conditions in either Lake Mead or Lake Powell.

Figure 2. Graph showing reservoir storage in different parts of the Colorado River basin since 1 January 2021.Note that water storage in Lake Powell increased greatly during the 2023 inflow season, declined thereafter until the beginning of the 2024 inflow season, increased again in spring 2024, and is now declining.

Despite the modest inflow season of 2024 when unregulated inflow to Lake Powell was only 83% of average, reservoir storage increased by 300,000 af, because losses from the basin’s reservoirs between mid-July 2023 and early April 2024 were less than the gains in storage that occurred in spring 2024[4]. The total decrease in storage between mid-July 2023 and early April 2024 was the smallest in the past decade and was primarily due to reduced consumptive uses in the Lower Basin.

One way to keep track of the loss in reservoir storage due to consumptive uses and losses is to monitor changes in storage that occur after the early summer peak occurs, as is depicted in Figure 3. For example, the dark blue line in Figure 3 was computed by subtracting the total basin reservoir storage on each day from the peak value of 30.0 million af that occurred on 6 July 2024. On 31 August 2024, total basin storage of 28.8 million af was 1.12 million af less than the early July peak. This amount of loss is midway in the range of reservoir loss that has occurred during the past decade. Reservoir storage declined little following inflow in 2017 (2017-2018); 2019 (2019-2020); and 2023 (2023-2024). Storage declined by large amounts following inflow in 2018 (2018-2019); 2020 (2020-2021); and 2021 (2021-2022). These data demonstrate that the current rate of decrease in reservoir storage has been “average” for the last decade but is much greater than the remarkably small rate of loss last year.

Figure 3. Graph showing the decrease in total basin reservoir storage in 2024 (2024-2025) following the early summer peak, compared with the decrease in some other years of the past decade. Loss in reservoir storage was greatest following the 2020 inflow season (2020-2021) and least following the 2023 inflow season (2023-2024). This year’s loss is midway between those extremes.

The rate of decrease in the combined contents of Lake Mead and Lake Powell since early July 2024 has been comparable to the loss in other years of small decline, as is evident in Figure 4. It is especially encouraging that storage in Mead and Powell greatly slowed since mid-August.

Figure 4. Graph showing the decrease in the combined contents of Lake Mead and Lake Powell following peak storage of 18.5 million af that occurred on 8 July 2024, compared with the decrease in some other years of the past decade. Loss in reservoir storage was greatest following the 2020 inflow season (2020-2021) and least following the 2023 inflow season (2023-2024). This year’s loss is similar to years when the loss in combined storage was relatively small.

The federally funded water use reductions approved last month by the Imperial Irrigation District and the federal government have made their way into the Bureau of Reclamation’s annual forecast model (updated Sept. 6 as I’m writing this), and the numbers are remarkable.

Imperial’s projected 2.2 million acre foot take on the Colorado River in 2024 is on track to be the lowest on record, with data going back to 1941.

California’s total projected main stem withdrawals are again under 4 million acre feet, the lowest they’ve been since the 1950s. Arizona’s main stem withdrawals remain under 2 million of their nominal 2.8 maf allocation for the second year in a row, basically the lowest they’ve been since the Central Arizona Project was built. Nevada is once again hovering around 200,000 acre feet of its 300,000 acre foot allocation.

Taken together, water use by the three lower basin states is currently on track to be the lowest since detailed record keeping began in 1964.

The Bureau of Reclamation has complete reported data back to 1964, when the modern accounting system was established as a result of the Supreme Court’s Arizona v. California decree. I have stitched that data together with a separate dataset that pushes California records back into the 1940s, assembled some years ago by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California and kindly shared with me. For my current version of the dataset, I extend a huge thanks to Sami Guetz, who spent time QA’ing it as part of her masters project at UC San Diego.