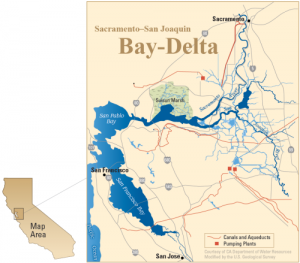

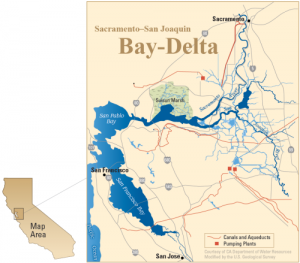

California’s Bay-Delta, courtesy CADWR

Ellen Hanak and colleagues at the Public Policy Institute of California stuck their necks out last week with

a scheme to move California’s Bay-Delta water conflict forward. It has a number of elements – I’d like to focus here on its proposal to “manage water for ecosystems, not just endangered species”:

To improve the effectiveness of environmental investments, California will need to move away from viewing water and land management activities in the Delta primarily through the lens of the Endangered Species Act. Instead, environmental managers should allocate water and restoration funds based on greatest overall ecological returns on investments.

This does not mean abandoning threatened or endangered species, but rather refocusing recovery efforts on ecological health, based on realistic assessments of the benefits of environmental water allocations.

The ESA: old, creaky

Environmental management via the 1973 Endangered Species Act has come to dominate the interface between environmental values and extractive human water use in the western United States. But it’s a pretty frustrating interface. The statute is old and creaky – a “static law meeting a dynamic world”, to slightly paraphrase UC Berkeley’s Holly Doremus (pdf).

The ESA’s language gives a nod to overall ecosystem health:

The purposes of this Act are to provide a means whereby the ecosystems upon which endangered species and threatened species depend may be conserved…. (emphasis added)

But its implementation nevertheless tilts toward a species-centric approach rather than a broader ecosystem perspective. That leads to the situation in New Mexico’s Middle Rio Grande, for example, where we expend intense effort on providing environmental flows to a relatively small section of the river where the endangered Rio Grande silvery minnow still survives, while largely writing off vast areas of the minnow’s original native habitat because the fish had been extirpated from those stretches of river long before it was declared endangered.

a new direction for the ESA?

The Hanak et al. piece echoes a strong thread in recent environmental policy scholarship on the ESA’s shortcomings. Here’s what my University of New Mexico colleague Melinda Harm Benson* wrote about this back in 2012:

[T]here is a need to shift management strategies from a species-centered to a systems-based approach. Chief among the shifts required will be a more integrated approach to governance that includes a willingness to reassess demands placed on ecological systems by our social systems. Building resilience will also require more proactive management efforts that support the functioning of system processes before they are endangered and on the brink of regime change.

I don’t understand the details of California’s Bay-Delta ecosystem well enough to opine on where it stands on Prof. Benson’s “brink of regime change” spectrum. But it seems as though more flexibility in defining and pursuing environmental goals there may provide some room for solutions that meet a broader range of our values and needs.

* shameless plug

Prof. Benson is in UNM’s Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, doing a lot of really interesting work in this area if you’re looking to further your education. In addition to her home base in geography, she’s also closely affiliated with our Water Resources Program, an interdisciplinary graduate program that mixes hydroscience with law and policy.

Albuquerque averages nearly 300 sunny days a year.