tl;dr There won’t be a grand bargain to reduce Colorado River water use before next month’s inauguration. But that doesn’t mean the grand bargain is dead. In fact, it is inevitable.

longer….

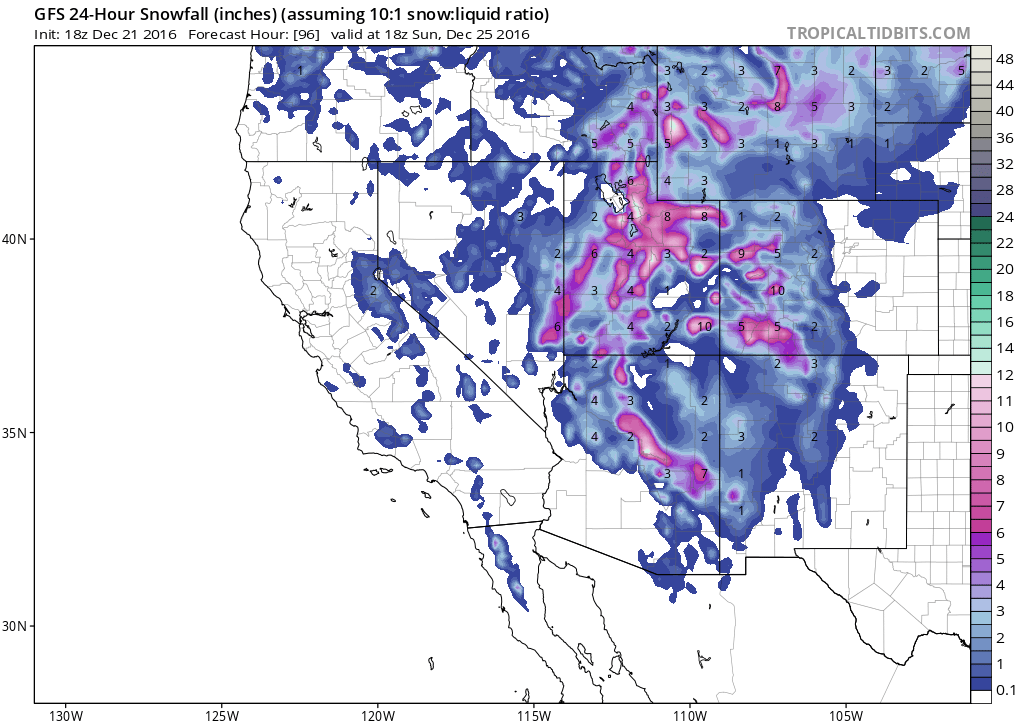

Lake Mead, December 2016

LAS VEGAS – When Jeff Kightlinger said during a public session yesterday at the Colorado River Water Users Association that a long-awaited deal to reduce water use on the river would not be completed before next month’s change in administration, it offered a very public answer to the question many of us brought to the Las Vegas meeting:

Would negotiators get a deal done before the Obama administration leaves office?

no, but….

Kightlinger’s short answer was “no”, but it’s misleading if we stop there (as I did in yesterday’s blog post). There’s a lot going on, and reason to be hopeful.

The annual CRWUA meeting is the traditional point in the calendar when big Colorado River deals are announced, but despite being very close, it’s been increasingly clear over the last few weeks that the final details remain out of reach.

The group of people I describe in my book as “the network” – has been red-lined in recent months, trying to work out the details of a complex deal to reduce the use of Colorado River water in California, Arizona, Nevada, and possibly Mexico. When I call my friends in the network lately, they’re almost always in airports or hotels or not answering my call because they’re in meetings.

The deal is the closest we have yet come to a formal recognition, attached to substantive actions, that the laws governing the Colorado River allocate more water on paper than nature provides in practice. For much of the last century, we’ve dodged the problem as population and therefore water use slowly grew into the available supply, but in the 21st century we’ve overshot, the big reservoirs (Lake Mead outside Las Vegas and Lake Powell on the Arizona-Utah border) have been drained to meet the demands of the basin’s farms and cities.

Commissioner of Reclamation Estevan López, speaking this morning at his final CRWUA, had perhaps hoped to be able to hand over the moment to one of his bosses to announce an agreement. He called the moment “bittersweet”. “We’re not there yet,” he said of the deal. “That’s the bittersweet part.”

López then went on to outline the major terms of the deal on which everyone seems to agree – larger cuts in water deliveries as Lake Mead drops, with the cuts first felt in Arizona and Nevada, and eventually in California. (I won’t rehash, you can find details here.)

protecting 1,020

López described what may be the most important feature of the deal – an agreement to “protect 1,020”, meaning that the Lower Colorado River Basin’s water users would agree to extraordinary water use cutbacks to prevent Lake Mead from dropping below the critical elevation of 1,020 feet above sea level.

At 1,020, there’s less than a years’ water left in the reservoir. A recognition that 1,020 is even possible, let alone that we have within view a plan to deal with it, is something that would have been unthinkable in Colorado River Basin management as recently as a decade ago, when the last grand bargain on the river, the Interim Guidelines for Lower Basin Shortages and Coordinated Operations for Lake Powell and Lake Mead, was being negotiated.

López called the nearly-done agreement “an emergency brake”, “a parachute”, “a way to slow things down”. Pick your metaphor, but whatever it is it is the clearest recognition in the history of Colorado River management that there is not enough water to use in the ways to which we have become accustomed.

There is, as Deputy Interior Secretary Michael Connor told reporters during a news conference yesterday, “a very good framework in place”.

But it is not yet done.

what happens next

I don’t fully understand why, other than that there are a lot of niggling details still being sorted, including the fate of the Salton Sea and Southern California’s desire for clarity on the Sacramento Delta, another of its water supply sources. (see here for more on that stuff) In addition to the deal itself, there are a series of side agreements required among the players, which in some cases must be approved by water agency boards, and a requirement for a vote of the Arizona state legislature. So even when the final agreement is agreed to, there remains work to turn the ideas into a substantive, binding deal.

I asked one of my friends working on the negotiations, one of the members of “the network”, whether she was going to make it home for Christmas, and she looked at me like I was crazy. As we near the change in administration, the frequent flier miles will continue to accumulate.

Connor said the goal is to have the package in good shape as it is handed off to the new administration. Whether it then would stall as the new federal team gives it a look is anyone’s guess at this point. Talking to people at all points of the political spectrum, it seems as though there is no clear “Democratic” or “Republican” position on this. Colorado River governance has never broken down along partisan lines. Given the names being mentioned in CRWUA hallway gossip for key Trump administration posts, there’s a good chance we’ll have folks in key positions who already understand the river and the deal.

Or not. Who knows what Jan. 21 holds?

the inevitability of a deal

But given the hydrologic reality, this deal or something very much like it appears inevitable. There seems to be no interest among the network’s members in litigating who gets how much water, and every incentive to do a deal that provides some certainty, even if the reality of less water is an unpleasant response.