PHOENIX – Drive south on Interstate 10 out of the Phoenix metro area, past Ikea, and the city ends abruptly, a sharp line between development and desert.

alfalfa fields, Stanfield-Maricopa Irrigation and Drainage District

Given its reputation for sprawl, Phoenix (when I say “Phoenix” here I’m talking about the whole metro area, not just the city itself) is remarkably compact. The realities of building a city in the desert – specifically the need for water – make it hard for a city to dribble beyond its margins. “The plumbing necessary to deliver water in support of people,” Grady Gammage wrote last year in his fascinating book on sustainability and Phoenix, “means that development in the desert is a phenomenon of concentration. A desert dweller cannot simply settle wherever he wants, drill a shallow and cheap well, and set up a subsistence farm. He needs access to communal systems.”

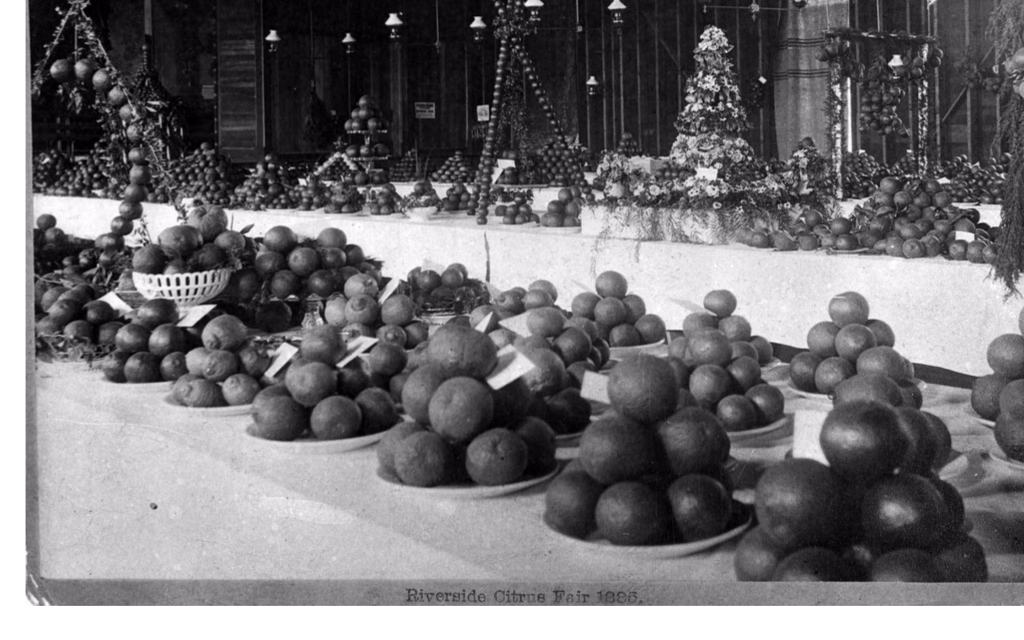

On the south side, the line is particularly sharp, as a spreading city bumps up against the Gila River Indian Reservation. But head southwest on Arizona 347 and the Sonoran Desert soon gives way to a working landscape. The Gila River Indian Community has turned its water rights into lush patches of farmland, as have the Ak-Chin, their neighbors to the south. And the Ak-Chin farmland blends seamlessly into the Maricopa-Stanfield Irrigation and Drainage District.

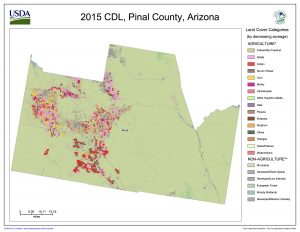

I’m in Phoenix this week for some meetings and to talk about my book, and I carved out some time to visit Pinal County, the stretch of mostly agricultural land that sits astride Interstate 10 between Phoenix and Tucson. When I say “mostly agricultural”, we’re speaking in relative terms here. It’s mostly desert, but to the extent there’s a human imprint, it comes in the form of alfalfa, cotton, and wheat, on Gila Indian, Ak-Chin, and Maricopa-Stanfield land.

At one point I pulled off to look at a recently irrigated alfalfa field and scared up a flock of sandpipers. They may have been yellowlegs, I didn’t get a good look, but as I stood taking pictures I heard the unmistakable squawking of killdeer, a bird from home, a call I recognize. There were a few dozen of each, lunching in the freshly watered landscape.

I tend to take for granted the categories of “nature” and “not nature”, but I’m intrigued by the conceptual blurring created by a flock of sandpipers in an irrigated alfalfa field and what that says about these coupled human-natural systems and the stories we tell about them. The old ecosystem services of a riparian wetland have been replaced by this alfalfa field. What does that mean?

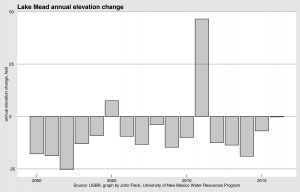

In general, the “Sun Corridor” (the “megapolitan” region that includes both greater Phoenix and Tucson) has followed a pattern of evolution from old agricultural land to city. Because the urban development generally uses less water than the farms it replaces, this has simplified the region’s water problems – ag-to-urban water transactions by way of real estate deals rather than water policy maneuvering.

But a few significant agricultural regions remain in the land around Phoenix – the valley of the Gila River out west of the city and Pinal County to the south. These remain very much working landscapes – this is primarily agriculture as a business, not “custom and culture” farming. It is a landscape defined by:

- agricultural economics, which determines which crops will likely be grown (the future of dairy here seems especially huge)

- water policy questions – who gets how much water?

- the law and policy around Native American rights to their own land and self-determination, and the resulting choices those sovereign communities make both about their own land and in their relationships with the communities around them

- a changing climate

- the changing shape of the economies of greater Phoenix and Tucson

All these things mash up together to create the future of that landscape. Seems like there’s a good story in here somewhere.