update: here’s a link to the full text of the Secretarial order

The Obama administration’s senior western water leadership this afternoon announced a Colorado River water management package that appears intended to signal a bridge for the administration transition, to continue work on nearly-completed deals to reduce the draining of the river’s big reservoirs.

The package falls short of two major deals some had hoped to be completed before the current team left – a deal with Mexico over future Colorado River water sharing, and a set of agreements among US states and the federal government to reduce water use in the Colorado River Basin, protecting the river’s beleaguered reservoirs. But it suggests that those deals are now the subject of widespread and bipartisan agreement, and appears to create a framework for continuity as the deals’ final details are worked out, rather than a risk of a sudden change in direction as the new administration takes office Jan. 20.

Lake Mead, December 2016

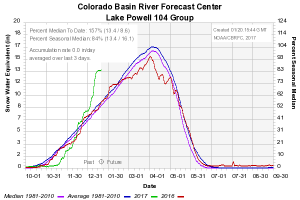

The package is embodied in a “secretarial order” signed this afternoon by Sally Jewell that includes new data suggesting that, without action, the risk to Colorado River water supplies is growing. Absent action, according to the new Bureau of Reclamation modeling runs, there is a one in three chance of Lake Mead dropping below the critical elevation of 1,025 feet above sea level by 2026. At that level, drastic water supply cuts to be needed to keep the reservoir from dropping to dead pool.

With the proposed actions discussed in Jewell’s order, that risk drops to about a one in 16 risk, according to the new USBR analysis.

From Jewell’s order:

Given the significant progress that has already occurred, and the commitment of the Seven Basin States and other key leaders to finalize the drought response actions, there is a very high probability that this work will be completed in the first half of 2017.

Quiet diplomacy?

As with much in Washington right now, what happens next is shrouded in uncertainty. But the deal appears to reflect quiet diplomacy between the Obama team and the incoming Trump administration to create a bridge toward solving these problems as the government changes hands later this week. I didn’t have time to catch Interior nominee Ryan Zinke’s testimony yesterday, but I’m told that in response to questioning from Catherine Cortez Masto, Zinke testified favorably about the nearly completed “Drought Contingency Plan” described in Jewell’s secretarial order. If true (anybody who watched, feel free to jump into the comments and elaborate) that would provide evidence for my hypothesis that the bridge is being built to try to ensure continuity in the final steps of working out these deals, and that the incoming administration may look favorably on this stuff.

Concrete steps

Jewell’s announcement includes concrete steps toward a near term reduction in Colorado River water use, including an agreement to pay the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona $6 million this year to forebear water use, leaving the unused apportionment in Lake Mead. That’s a critical piece of Arizona’s part of the complex water saving deals now being negotiated. While the amount of water is relatively small, it fills a critical political and policy niche by demonstrating a new path to reduced water use in Arizona.

The deal also adds an addendum to an agreement between the federal government and the Salton Sea. Dealing with the Salton Sea is critical (see my Sacramento Bee piece from last month for details on why). Jewell’s move here is an effort to bolster efforts to deal with the Salton Sea problems, which is critical to winning support in return from the giant Imperial Irrigation District for the water use deals.

Jewell’s order also sets out an interesting set of steps to be implemented should further negotiations to finalize the water-saving agreements among the states fizzle, including this: “undertaking a review of the Secretary’s authorities under the Law of the River to implement policies that will reduce depletions in the Lower Basin”. Of course any order by the old Secretary of the Interior can be un-order by the new one, but this provides a threat in the background – if the states don’t work out the final details of a deal, the federal government should at least consider stepping in and ordering action to protect Lake Mead.