The always thoughtful Mike Dettinger:

Calling the long term groundwater depletion (overdraft) part of the drought is blaming a thing we've done to ourselves on the weather. https://t.co/bWI6arxSXY

— Michael Dettinger (@Mdettinger) February 27, 2017

The always thoughtful Mike Dettinger:

Calling the long term groundwater depletion (overdraft) part of the drought is blaming a thing we've done to ourselves on the weather. https://t.co/bWI6arxSXY

— Michael Dettinger (@Mdettinger) February 27, 2017

Talking this week to members of the Colorado River water governance brain trust at the Family Farm Alliance‘s annual gathering in Las Vegas, there was a weird vibe about the big snowpack building in the Rockies.

My quick take based on the February USBR modeling plus the latest forecast info from the CBRFC Lake Powell could pick up 4 million acre feet this year, and with a likely release of some bonus water through the Grand Canyon for downstream users, Lake Mead could stabilize.

These numbers have substantially reduced the pressure to finalize a “Drought Contingency Plan” to reduce use of Lake Mead water in the Lower Basin and prepare for possible Powell shortfalls in the Upper Basin. All that extra water and breathing room must be a good thing, right? The weird thing was the tenor of some of the resulting conversations. The DCP deal is important, and it was really close. Now, to some folks, it’s looking less urgent. With the pressure reduced, some of the key players seem to be using the opportunity to drive harder bargains (or dig their heels in to avoid hard bargaining) – on the complex shortage distributions within Arizona, for example, and on the Salton Sea.

For those trying to get the damn deal done, the big snowpack is a setback.

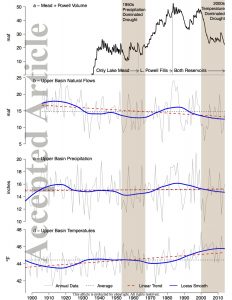

So it’s worth reminding ourselves where we’re at. From the perspective of the last few years, a 4 million acre feet bump is great news. But as the graph above makes clear, we’ll still end up the water year down 20 million acre feet from the start of the 21st century. We’re along way from being out of the hole.

Bellagio fountain, February 2017

Some years ago, on one of my first reporting trips to Las Vegas for my book, a friend who introduced me to the fountain in front of the Bellagio Hotel suggested a bit of economics that lingered. He pointed up to the big hotel and ventured a guess at the revenue flowing through it – a rough billion dollars a year.

His idle comment turned into this fun bit of business in my book Water is For Fighting Over: and Other Myths About Water in the West:

The Bellagio’s fountain, often mocked as a symbol of water excess in the arid Southwest, may in fact represent some of the highest-value water around. The 12 million gallons a year needed to keep it topped up starts as water too salty to drink, drawn from an old well that once irrigated the Dunes Hotel golf course. Twelve million gallons sounds like a lot, but it’s really just enough to irrigate eight acres of alfalfa in the Imperial Valley. Total revenue at the seven giant casino–resort hotels contiguous to the fountain, at the corner of Flamingo Road and South Las Vegas Boulevard—the heart of the famed Las Vegas Strip—is an estimated $3.6 billion…. Given the crowds lining the sidewalks for each one of the fountain’s dancing-water shows, the fountains must represent one of the most economically productive uses of water you’ll find in the West.

I’m in Las Vegas this week the annual meeting of the Family Farm Alliance, an ag irrigation NGO. (Fascinating meeting, interesting people.) After the sessions ended, I wandered up the strip to hunt for dinner and ended up, as I often do, at the Bellagio fountain. The Friday evening crowd was swelling, and the 6 p.m. fountain show’s music was Henry Mancini’s Pink Panther Theme.

Peak Vegas.

In Reno, a record year seven-plus months early

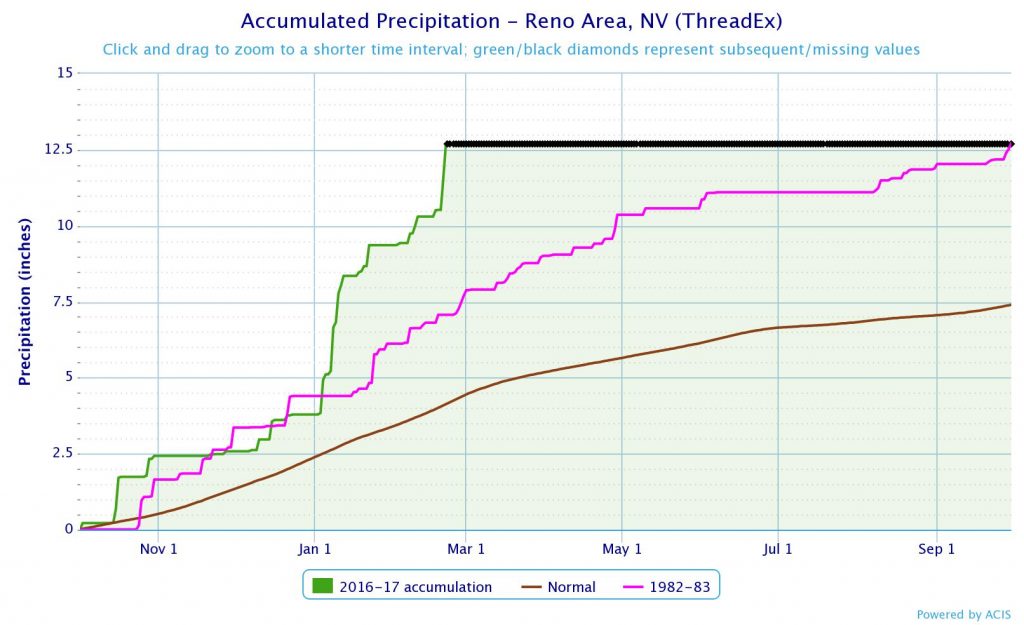

This is “water year” precipitation in Reno, Nevada, from Oct. 1 to Sept. 30. The brown line is an average years’ accumulation. The pinky-purple line is 1982-83, the all time wettest year on record, going back to the 1890s. The green line is this year.

Folks, 2017 has already eclipsed Reno’s wettest year on record with more than seven months to go.

We’re devoting a lot of attention in the Colorado River Basin to preventing “shortage”, which will happen if Lake Mead enters any given year below elevation 1,075. The discussions are around a new “Drought Contingency Plan” that would reduce water use in the basin, heading off the risk of 1,075 (now at a one in three chance for 2018, though that calculation was done before the latest round of Upper Basin snow).

Deputy Interior Secretary Mike Connor at the San Luis Bridge, March 28, 2014, watching the delta pulse flow

But the real risk is not 1,075, it’s really 1,025. Under the current operating rules, we could drop from 1,075 to 1,025 in a hurry, and at that point we’d be very close to a system crash in which lots of people don’t get water. As former Deputy Secretary of the Interior Mike Connor pointed out in a 2014 interview with me, the real risk is when Lake Mead drops to levels so low that the risk of catastrophic shortages is high and we lack the rules to deal with it. Here’s the scene from my book:

As we turned from the river to ferry Connor back to the Yuma airport for his flight home, the talk turned to the serious next steps. At that time, the Bureau of Reclamation’s internal modeling efforts showed the potential for drought and climate-change trouble ahead. As Lake Mead drops, rules kick in that require water users in Nevada, Arizona, and Mexico to remove less water from the system each year. But those reductions are modest, and Connor told me that the Bureau’s worst-case modeling showed that even with the agreed-upon reductions, Lake Mead could quickly drop past a point of no return, to levels at which the current rules would be no help in determining who was entitled to how much.

Connor, who since leaving Interior at the end of the Obama administration has been named a Walton Family Foundation Environment Program Fellow, explained it this way in an interview published last week:

People will start to get nervous because there is not a plan in place on how to manage water allocation in the lower Colorado River if Lake Mead drops to critically low levels below 1,025 feet. The potential for a very sharp decline in lake levels will unsettle everyone.

The thing is, the near term actions being taken in the Drought Contingency Plan to reduce the risk of a 1,075 shortage will also help establish a framework to manage much lower levels, by reducing water use by all the states of the Lower Basin.

A good snowpack in the Rockies has reduced the risk. But it has not gone away.

High temperatures mean less water on the Colorado River

A warming climate is already reducing the flow in the Colorado River, and the future risk is large, with a worst case of the river’s flow being cut in half by the end of the century, according to a new study from a pair of the region’s leading researchers. While precipitation declines since the turn of the century have been modest, Brad Udall and Jonathan Overpeck found, a little less rain and snow have translated to a lot less water in the river:

Between 2000 and 2014, annual Colorado River flows averaged 19% below the 1906-1999 average, the worst 15-year drought on record. At least one-sixth to one-half (average at one- third) of this loss is due to unprecedented temperatures (0.9°C above the 1906-99 average), confirming model-based analysis that continued warming will likely further reduce flows.

Their analysis suggests substantial risk going forward:

Recently published estimates of Colorado River flow sensitivity to temperature combined with a large number of recent climate model-based temperature projections indicate that continued business-as-usual warming will drive temperature-induced declines in river flow, conservatively -20% by mid-century and -35% by end–century, with support for losses exceeding -30% at mid-century and -55% at end-century.

While we have seen projections of the future impact of climate change on the Colorado for more than two decades, this study is important because it is one of the first to argue empirically that the change is already underway. (See also Woodhouse and colleagues last year, which I wrote about here.)

Key to the new paper’s argument is a comparison between the previous worst 15-year drought on the Colorado River, from 1953-1967, and the current one. As measured by precipitation, the ’50s were a lot drier than now. But the current drought, which began in 2000, is a lot drier in terms of river flow. The difference? It’s a lot warmer now than it was back then.

Such temperature-driven droughts have been termed ‘global-change type droughts’ and ‘hot drought’, with higher temperatures turning what would have been modest droughts into severe ones, and also increasing the odds of drought in any given year or period of years [Breshears et al., 2005; Overpeck, 2013]. Higher temperatures increase atmospheric moisture demand, evaporation from water bodies and soil, sublimation from snow, evapotranspiration (ET) from plants, and also increase the length of the growing season during which ET occurs.

The results are not a surprise. It seems like at every Colorado River conference I’ve attended over the last few years, either Overpeck or Udall have been on the agenda presenting preliminary “work in progress” results on this. Beyond the stark data, they’ve been making two points. The first is the need for much more serious adaptation measures to cope with the reality of having less water.

This means using less water.

The second, and more important point for the two researchers, has been the imperative to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to protect the future of the southwest’s Colorado River-using communities:

The only way to curb substantial risk of long term mean declines in Colorado River flow is thus to work towards aggressive reductions in the emissions of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

A remarkable piece in this morning’s New York Times about urban residents’ drive for water:

MOSUL, Iraq — The water taps are dry in Rashidiya.

The water and sewage system collapsed in this eastern Mosul neighborhood after 100 days of street combat. On Sunday, Haitham Younis Wahab and his neighbor Shamsuldeen Ahmed Saed decided to do something about it.

Out came the sledgehammers, steel pipes and shovels.

The two men pounded and dug for three days. Sixteen feet down. Twenty feet down. Nothing. And then, 26 feet beneath the cracked sidewalk, they struck water. After all, they live just a half mile from the muddy Tigris River, which divides eastern and western Mosul.

It is not drinkable, David Zucchino and Ben Solomon report. But it is something.

From the OED:

war: a. Hostile contention by means of armed forces, carried on between nations, states, or rulers, or between parties in the same nation or state; the employment of armed forces against a foreign power, or against an opposing party in the state. (emphasis added)

Going to court – an institution that provides a peaceful alternative to armed conflict – is pretty much the opposite of “war”.

My friend and University of New Mexico water nerd colleague Bruce Thomson has found some timely reading for us – The Dam, a novel by Robert Byrne. Bruce is on UNM’s engineering faculty and taught our engineering ethics course for many years. Quoting Bruce:

It’s a short novel (244 pages) about a young engineer who recognizes there’s a potential failure mode for a large earth filled dam and his efforts to have this flaw recognized and dealt with before the dam fails. It’s got a very nice description of earth filled dams, their design, construction, and potential vulnerabilities, and ultimately the series of events leading up to and following failure. It also describes the challenges that a young engineer faces in getting the attention and subsequent action from supervisors, managers, and politicians. I have used the book in my engineering ethics class as it addresses situations that engineers are likely to encounter, though usually not with such dire consequences.

Worth noting is that, while the dam in the book is not “Oroville”, it’s pretty clearly Oroville:

I read the book again last night. It’s a fictional earthfill dam, highest in the country, in Sutter county upstream from Suttonville, 100 miles NE of Sacramento. It is clearly based on the Oroville dam and lake, though in this book it’s the dam that fails not the spillways.

Timely fiction.

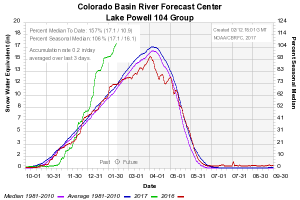

We’re going to need a bigger graph.

While we were all distracted by the chaos at Oroville Dam, the snowpack above Lake Powell on the Colorado River last week climbed above normal for the year. By this measure from the CBRFC, it’s at 57 percent above average for mid-February. It doesn’t usually peak until early April.

Based on the latest round of forecasts, expect it to keep rising. This is good news for levels in Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the two large reservoirs that provide storage for basin water users.

The current model estimate for April – July flow into Lake Powell is a staggering 3.5 million acre feet above the Jan. 1 forecast. To get a sense of the scale of that, Lake Powell currently holds 11.2 million acre feet of water. 3.5 maf is a meaningful increase in storage. The Bureau of Reclamation’s monthly operations report, out today, projects Powell ending September with a surface elevation of 3,640 feet above sea level, 32 feet above the forecast just a month ago.

But beyond gobs of water, what does it mean? First and most importantly, it puts off the risk that Lake Powell could drop to a level that puts at risk the ability of the Upper Colorado River Basin to meet its delivery obligations under the Colorado River Compact. The bureau also has concluded it is likely there will be enough water in the system to release “bonus” water from the Upper Basin to the Lower Basin, helping prop up Lake Mead with a release of 9 million acre feet this year, above the minimum required release of 8.23 maf. (Though as astute Inkstain reader Charles notes, the rules are complicated and we’ll have to wait until April to know for sure about this.)