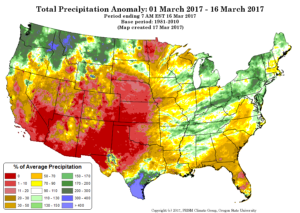

The Rio Grande through Albuquerque has been rising this week, thanks to a combination of a great snowpack and a quirk in the river’s operating rules.

The snowpack part is obvious – it’s big and melting fast – the rule quirk less so. Under Article VII of the Rio Grande Compact, we cannot store water in most of our upstream reservoirs unless Elephant Butte Reservoir (the downstream reservoir that delivers water to Texas) is above a 400,000 acre foot threshold. It is not, so the rules require the Bureau of Reclamation and the Corps of Engineers, the managers of the upstream dams, to pass all the water. The rule quirk has weird subquirks involving Pueblo communities’ water rights, which I’ll leave as an exercise for the law students in the audience. But the bottom line is that flows through Albuquerque are up by a thousand cubic feet per second today compared to a week ago, because Rules.

six crossings of the Rio Grande

Last night I lay on my couch intently staring at maps on my iPad for more than an hour, plotting. The result – a morning bike ride that looped and twisted and turned to include all six of Albuquerque’s crossings of the Rio Grande.

A bicycle is a great way to see one’s place. The spatial and temporal scale – in a morning I can cover a big chunk of Albuquerque at a speed slow enough to ponder – combined with the physicality of moving your own body across the landscape, builds an intimate geography.

My friend Andrew has gotten me hooked on Strava, a web-based tool for tracking your bike rides. You slap one of those GPS goobers on your bike, download the data, and the fun begins. (Heatmaps!) I started more than a year ago after Andrew told me that municipal planners use Strava data to help make bike route decisions. Most of my riding the last couple of years has been commuting, and helping planners identify commuting patterns seemed like a useful contribution.

Lately, though, I’ve become enamored with the performative, social aspects of the thing.

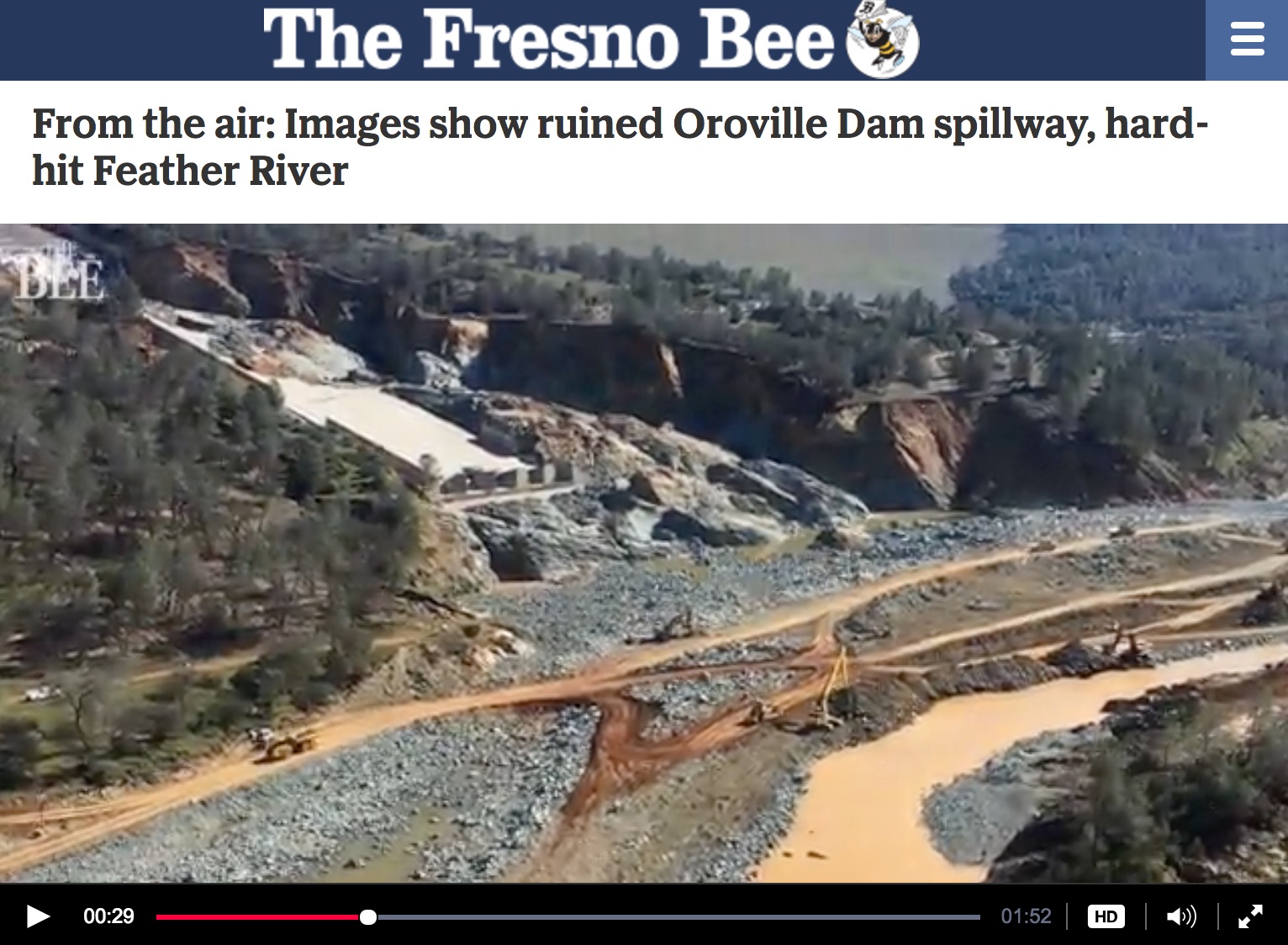

Rio Grande at Bridge Boulevard (yes, we have a bridge named “Bridge”)

Andrew moved recently (boo), but it’s been fun to “watch” him explore his new town via his Strava feed. Strava is designed for the spandex crowd, with things like “suffer scores” and timed interval reports and such, and its Facebook-style use thus lends itself to a kind of public performance. This is not me. I am old, and slow. But with words and pictures it also opens the possibility for little stories. There was comedy, for example, as one of Andrew’s carefully planned routes in his new town failed at a large stairway.

So I planned my route with care, knowing that my Albuquerque friends could take amusement at the zigs and zags and curlycues needed to hit all the bridges as I worked my way back and forth up the Rio Grande Valley. With a picture of the river at each crossing.

My water obsession means our routes, when we bike together, often include detours to get a picture of the Rio Grande. So even though I was riding by myself, this ride had a social element.

I eagerly await their criticism – “There are really seven crossings, John, what about Alameda?” – and the argument that will ensue and the planning for another ride that adds the seventh bridge. Or maybe the eighth, out in Bernalillo?

I’m old and slow, and that’s kind of far, but not out of the question.