One of the great joys of bicycling socially is route sharing.

Albuquerque is a great bicycling city. We’ve got a nice network of trails that are completely separated from streets, including one along the Rio Grande that runs the whole length of the metro area. We’re seeing more and more facilities on the streets as well – protected lanes, bike boxes, that green colored pavement that acknowledges that the bikes belong here too.

With my new job at the university, I can commute by bike – it’s close, and the neighborhood has a high density of cyclists, which increases safety because drivers are used to us. Lots of my students ride.

But inevitably, as you build new bicycle infrastructure, that infrastructure has to end somewhere. The network is increasingly interconnected, but there will always be gaps. “So how do you get from X to Y?” is a common conversation among cyclists – where do you cross Lomas, how do you get up from the river through downtown, and most importantly, always, where do you cross the freeway?

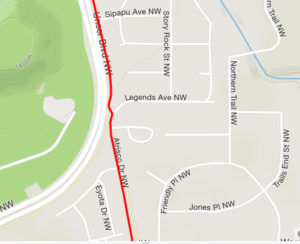

the trick to get from the “Powerline Trail” on Albuquerque’s West side to Atrisco

I still identify a lot of my rides with the people who shared their little tricks for stitching the network together. Last Sunday, my old friend Scot showed me where to “portage” across a big dirt patch to get from Tramway Boulevard to the bike trail that heads back down in my neighborhood. Today it was new friend Dan leading Scot and I through the zigs and zags to connect up the “Powerline Trail” on Albuquerque’s west side (it’s real name is something more poetic, but one of Dan’s tricks when the trail goes through a few awkward zigs and zags on the neighborhood streets was to watch the big overhead power lines – trails follow infrastructure).

The little kink in the route on the map to the right (yes, we are nerds, we GPS our rides) gets you from the Powerline Trail to Atrisco Dr., which you can then follow all the way back, with a few zigs and zags (thanks Dan and Scot!) to the Atrisco Neighborhood, down by the river. The city has a great bike system map, and Scot carries a paper copy. But the wisdom of the zigs and zags comes from the shared knowledge learned by a posse of Albuquerque riders working out the tricky bits and sharing what they learned.

The Copenhagen left

As we were passing under the railroad tracks on Tijeras-Martin Luther King Boulevard, we caught up with a dad riding the bike lane with his two young daughters. They were on their way to a birthday party. We dawdled and chatted before going our separate ways as the dad taught his daughters how to do a “Copenhagen left”.

Passing on the lore.

We’ll be analyzing lessons from California’s drought for a while yet. But what I view as the most important lesson is already clear.

We’ll be analyzing lessons from California’s drought for a while yet. But what I view as the most important lesson is already clear.