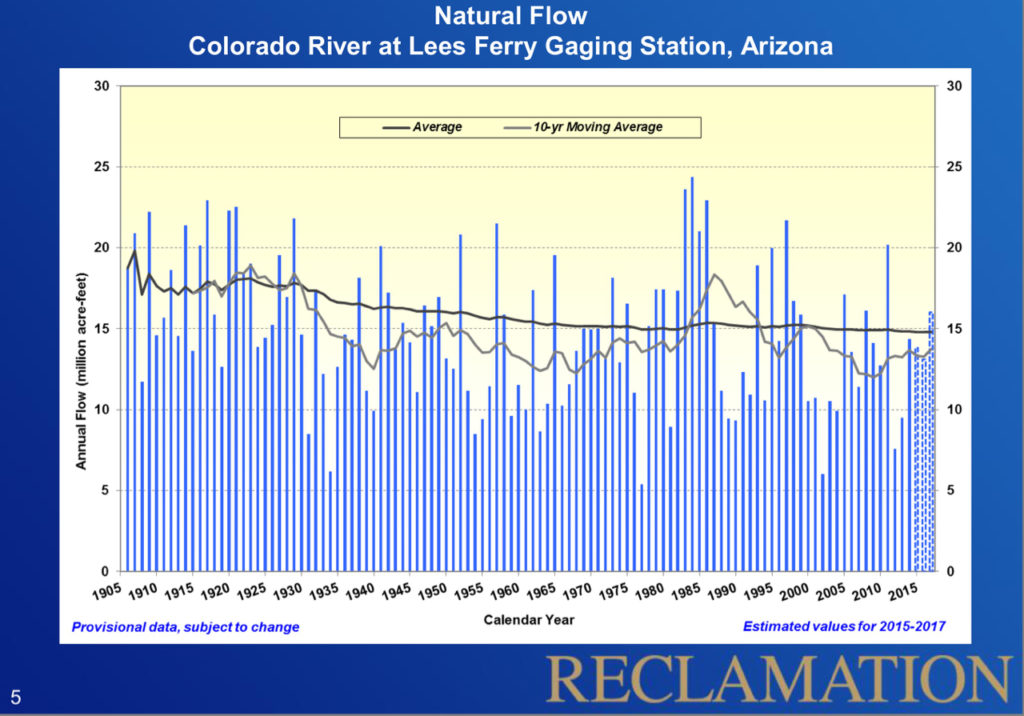

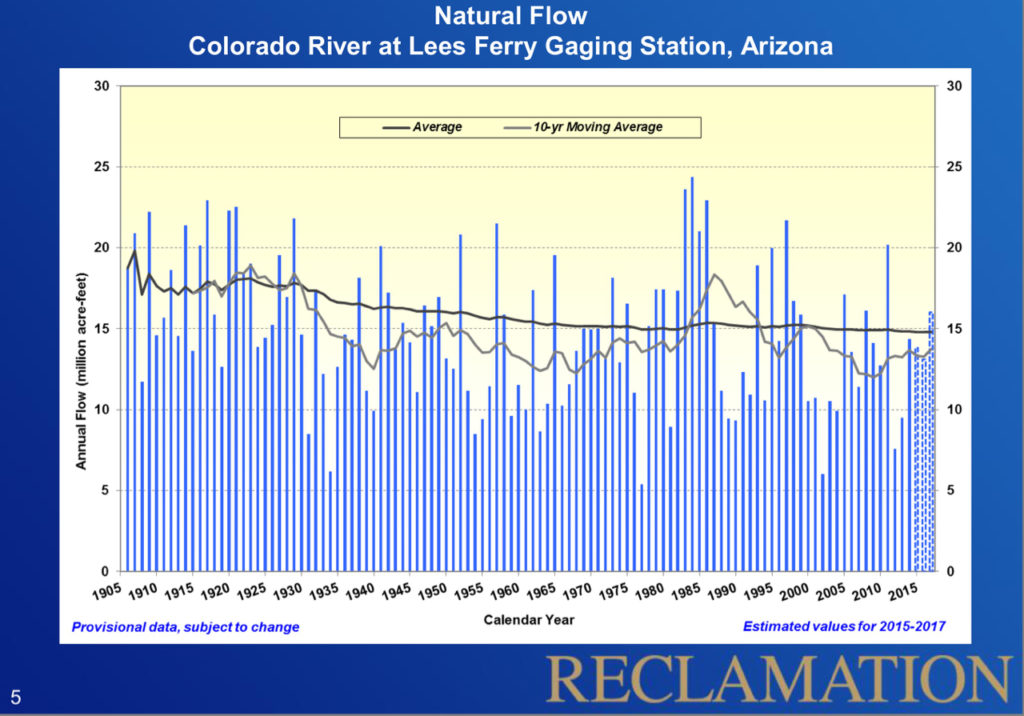

This is only the fourth year since the turn of the century with above-average flow on the Colorado River.

Colorado River flows

This is only the fourth year since the turn of the century with above-average flow on the Colorado River.

Colorado River flows

I said some stuff about water markets in this Q&A with Drew Beckwith of Western Resources Advocates:

Beckwith: That’s certainly an NGO concern, that an unbridled market does not take into account the environment and that water would just run uphill towards money.

Fleck: This is a problem with thinking about markets, right? A market is built by humans to meet a need. So you can build a market that would include environmental values for water and have an institutional framework that pays farmers to leave water in-river for an environmental purpose. It’s just an implementation detail of building a market, it’s not intrinsic to markets. This is a question of where you draw the boundaries in and around the market and what do you include. Markets are built by people to accomplish particular goals. They’re not some magic thing off on the side. This is one of the failures of our public understanding of economics that’s gotten us in all kinds of trouble. People build markets.

Through much of Albuquerque, the Rio Grande flows between levees at a grade slightly higher than the surrounding valley floor.

As a result, storm water must be pumped over the levees into the river’s central channel, with a string of pumping stations and big pipe outfalls like this, on the east side of the river just north of the Avenida Cesar Chavez bridge.

flood plain connectivity, Rio Grande style

McClatchy’s Stuart Leavenworth has details on the nominee to be of Deputy Interior Secretary, one of the key positions top the federal bureaucracy that helps manage western water:

His name is David Longly Bernhardt, and he’s worked as the top lobbyist for California’s Westlands Water District, the largest agricultural entity of its kind in the nation. He’s sued the Interior Department and helped write legislation on behalf of his client. Largely because of his services, Westlands has paid Bernhardt and the law firm where he works $1.27 million since 2011.

My UNM faculty colleague Caroline Scruggs and soon-to-be-graduate of both Community and Regional Planning and the Water Resources Program Jason Herman have a new paper on the costs of treating and reusing wastewater. Caroline and her students have been looking closely at the issue in the context of small inland communities, which are increasingly eyeing both direct and indirect potable reuse as a supply option:

We find that the present worth for indirect potable reuse is substantially higher than for direct potable reuse because of additional pumping and piping requirements, and scenarios including reverse osmosis for advanced treatment have significantly higher present worth values than those including ozone/biological activated carbon. Costs aside, any scenario must also be acceptable to regulators and the public and approvable from a water rights perspective.

From the Arizona Municipal Water Users Association on the question of who speaks for Arizona on Colorado River issues:

The feud within Arizona over who’s in charge of the state’s Colorado River water – the state Department of Water Resources or the Central Arizona Water Conservation District – escalated this week.

This is from an April 25 “cease and desist” letter (obtained by me through a state public records act request) from the Arizona governor’s office and DWR to CAWCD (the entity that operates the Central Arizona Project):

This is super arcane legal stuff, but the underlying conflict has been a serious setback to Arizona’s progress on Colorado River Basin-wide drought contingency planning.

Excellent background in this from Kathleen Ferris.

Click on the “view entire document link” to see the whole letter.

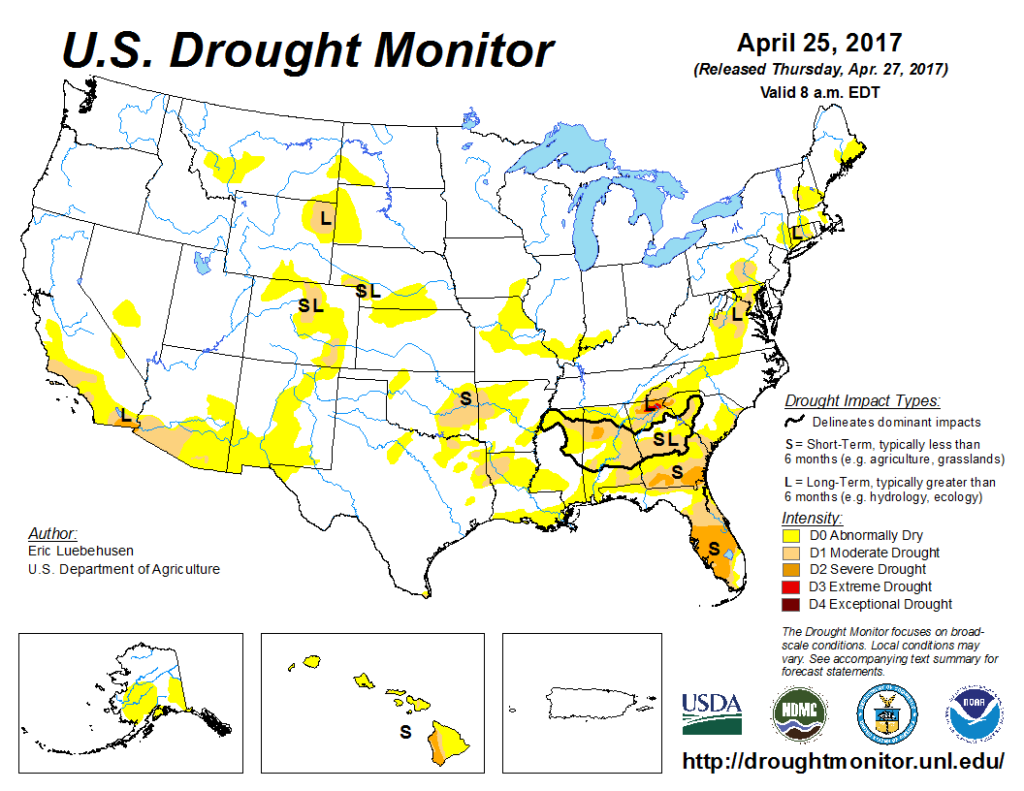

78.33 percent of the United States is in “not drought or abnormally dry” conditions in this week’s Drought Monitor. That’s the best we’ve seen since June 2010.

not drought monitor

In writing this note, I am reminded of the linguistic dilemma posed by our lack of a good word for “not drought”.

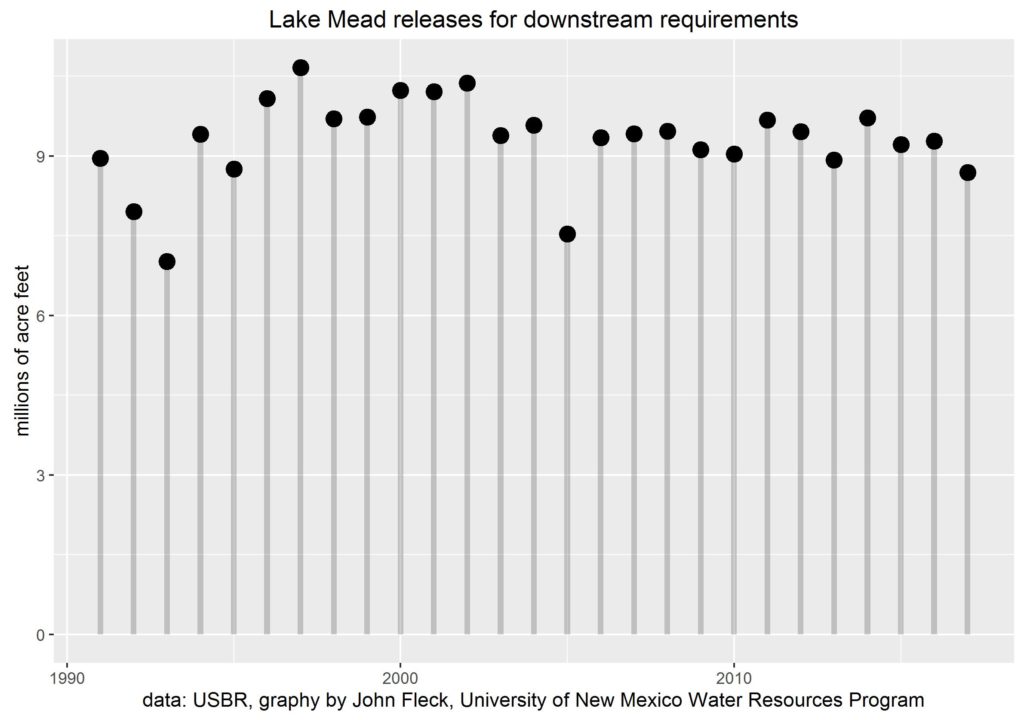

Amid the Colorado River water management attention last week rightly focused on the fact that a wet winter in the Upper Basin means a big release this year from Lake Powell to help refill Lake Mead, I missed another bit of business that may be even more important.

The Bureau of Reclamation’s planning model is forecasting an 8.687 million acre foot release to meet downstream needs this water year – Arizona, California, Nevada, Baja, Sonora, plus system losses. This would be the lowest downstream demand since 2005, and continues a general downward trend dating to the late 1990s:

Releases from Lake Mead

When people have less water, they use less water.

water tank at Toadlena

Lovely Felicity Barringer piece on our language of water. My favorite bit:

In a bone-dry landscape like the Navajo reservation at the corner of Utah, Colorado, Arizona and New Mexico, water names proliferated. Places like Tohatchi and Toadlena, New Mexico or Tonolea, and Tolani Lakes, Arizona, begin with tó, the Navajo word for water.