“A lively debate, provocatively labeled ‘conservation in the Anthropocene,’,” my University of New Mexico colleague Ben Jones and collaborators wrote last year, “has been taking place over what conservation, and related notions of naturalness and preservation, means where large natural systems are increasingly inter-connected or coupled to human systems.” In particular, Jones et al. were interested in the Colorado River and Glen Canyon Dam, and the proper incorporation of the range of communities and values that must be incorporated in decision making regarding the dam and its relationship to the larger “coupled human and natural system.”

Ben is (and I am) using the word “anthropocene” here not in the formal geological sense – a grand debate over where we’ve entered a new “-cene” defined by an identifiable geologic layer of human stuff. Rather we’re using it in the broader sense in which it has migrated into public discourse, the way David Biello was using it in a book review essay in today’s New York Times:

The waterways of the West now exist as monuments to an ambitious desert civilization. Across this vast region of America, few, if any, rivers flow without hosting one or more dams, concrete channels, diversions or other human-made “improvements” that allow people and farming to flourish in this dry country. And few, if any, rivers reveal this unnatural world more than the Colorado, which no longer reaches the sea or carries along its entire 1,450-mile length much of the reddish silt that inspired its name.

Downstream from Glen Canyon Dam, the Colorado River is green not the red of its name. Navajo Bridge, May 2017, photo by John Fleck

When I was deep into work on my book, a friend over beer was quizzing me about where I in was in the project, what I was writing about. The friend, a law professor, was doing what law professors do I guess, that sort of Socratic questioning that ultimately led me to the realization that while I said I was writing a book about the Colorado River, what I was really writing was a book about what happens with the water once we take it out of the Colorado River. It was a striking realization, with which I ultimately made peace, and it was an important insight both for the book and for how I think about the river and my work going forward.

Biello’s NYT piece, a review of David Owens Where the Water Goes, goes full Anthropocene on this point:

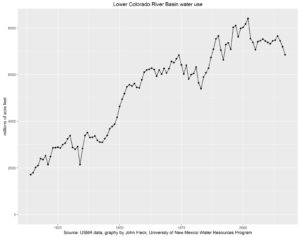

The people of the Western states, in collusion with the federal government, have opted for irrigation, power and sprawling cities in the desert like Los Angeles and Phoenix. The glass of Colorado River water is either half-full or half-empty, depending on whether you think water woes bring out the cooperative side of people, or the litigious. As Owen discovers on his journey, both are true — lawyers and legislators make a good living adjudicating claims, but owners of water rights also often work it out among themselves without drying anybody out. This is a system that muddles through on a blend of threats and collaboration, with the underlying understanding that everybody must win or everyone will lose, as the longtime water reporter John Fleck explores in his illuminating recent book “Water Is for Fighting Over.” It remains to be seen what the likely shortfall of rain and snow brought by global warming will do to this already fraught series of arrangements.

The river here is defined now by our decisions to take water out of it, and by the “fraught series of arrangements” with which we try to manage the problems that are upon us now that the Colorado seems to be running short. It is simply impossible to think of the Colorado absent those fraught arrangements and the implications for the “irrigation, power and sprawling cities in the desert like Los Angeles and Phoenix”. It is in fact a coupled human and natural system, deeply coupled.

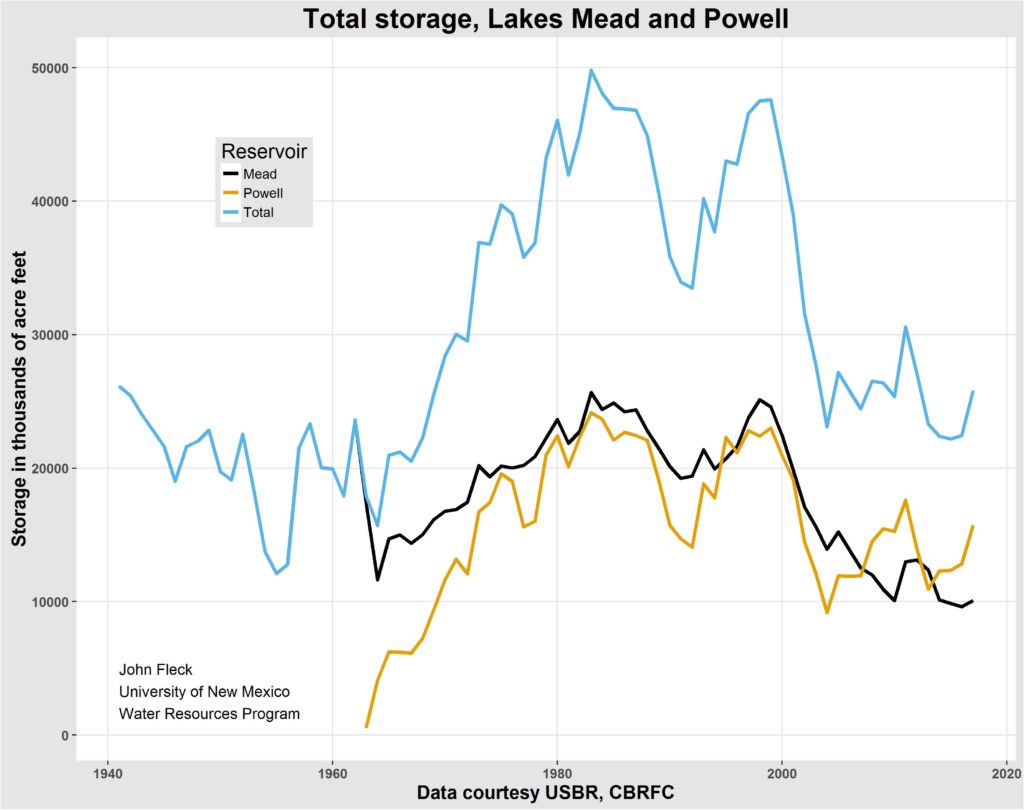

In the distance, Lake Mead, where we spread our water out to dry in the desert sun

This is the painful realization at the heart of Frederick Reimers’ piece last week in Outside Magazine about the dreamers who would drain Lake Powell and free Glen Canyon. “Fill Mead First”, the dreamers’ scheme, would move Powell’s water downstream to Lake Mead, emptying Glen Canyon Dam. It’s premise is classically Anthropocene – that because of Powell’s seepage and evaporation losses, you could save water for human use and free up Glen Canyon as a happy side benefit. As I’ve written before, the best science suggests that those savings are not to be had. But there’s also something wonderfully Anthropocene about the whole argument, as Reimers writes:

Without Powell, more dams could be greenlighted upstream to replace that storage capacity, meaning free-flowing sections of rivers that feed the Colorado—including the Gunnison, Yampa, and Green—could be compromised. Water diversions could be built, too, pulling enough water from the river that it might not even flow in some stretches.

It’s a coupled system now. There’s no uncoupling.

In the end Biello’s NYT piece, and Owen’s book, and mine, all point to a narrow but hopeful path. All three of us point to Minute 319, the US-Mexico agreement that returned water, however briefly, to the Colorado River Delta, left dry by all of that water we take out to use elsewhere. Here’s Biello:

Part of the work of the next few decades is to imagine and build a better future rather than letting inertia reign.

Perhaps that better future allows the Colorado River to flow along its entire course, restoring a once lush wetland teeming with life while also allowing for all the human uses along its length. That delta has been dead for more years than I’ve been alive, killed by the filling of Lake Powell, which means everyone born after 1963 accepts this as the normal state of affairs. But there is no reason I or my children couldn’t see Lake Powell and the delta. Our hand is on the faucet of a formerly natural, unpredictable waterway; what will we do with that power and responsibility?

This is a fundamentally different narrative than the old stories of Cadillac Desert and A River No More, stories of humanity’s sins against nature and our coming punishment. It’s a narrative I’m happy to be a part of.

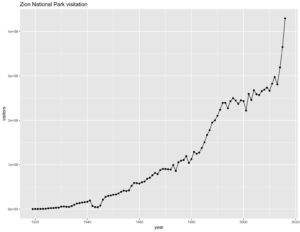

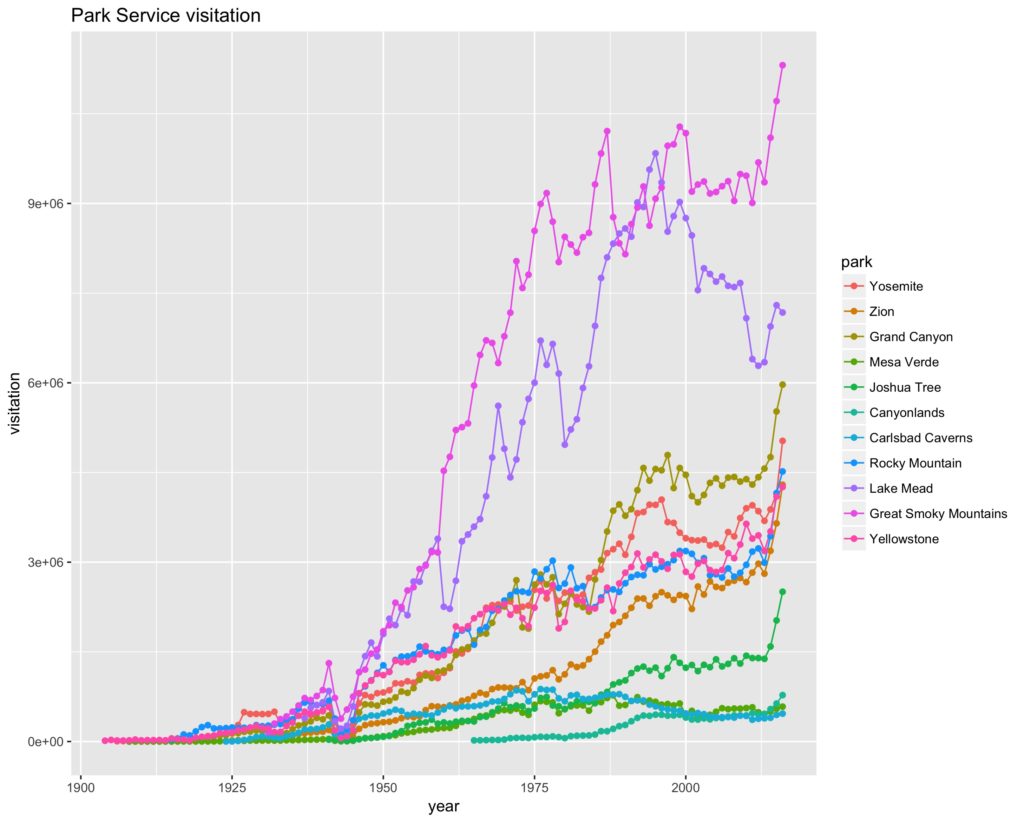

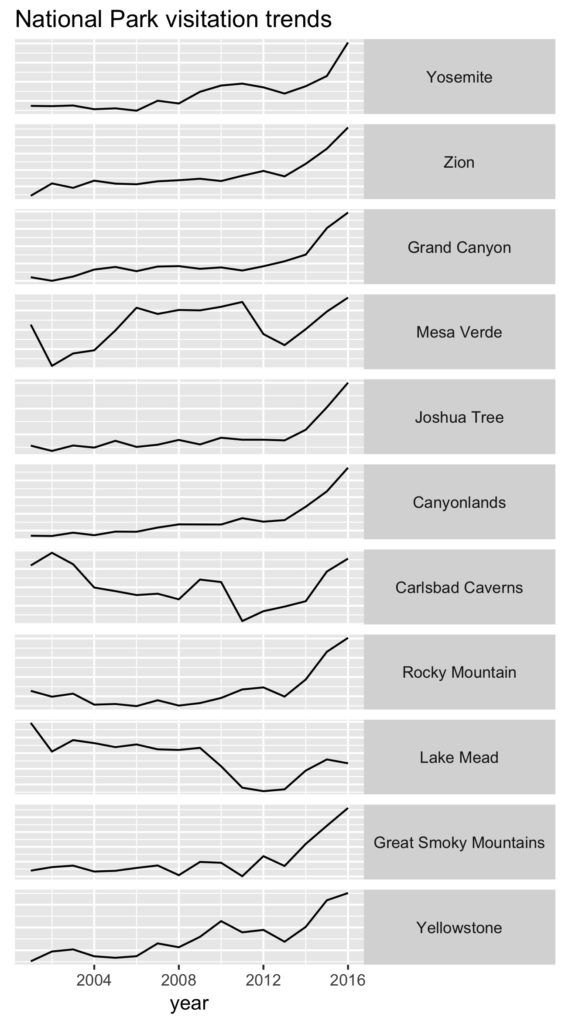

Here’s another attempt at a visualization, a tiny multiples graph showing each of the parks I looked at from 2000 to the present, without vertical scale and a non-zero baseline, just to get a feel for the shape of the curve for each park. You can see that every park save Lake Mead (a National Recreation Area, not a “park”) has a jump beginning in 2014.

Here’s another attempt at a visualization, a tiny multiples graph showing each of the parks I looked at from 2000 to the present, without vertical scale and a non-zero baseline, just to get a feel for the shape of the curve for each park. You can see that every park save Lake Mead (a National Recreation Area, not a “park”) has a jump beginning in 2014.