In 1940, Los Angeles County had 250,000 acres of harvested cropland. By the end of World War II LA County was, by far, the most agriculturally productive county in California. In the most recent Census of Agriculture, conducted in 2012, acreage had declined to just 40,000 acres and LA County was but a minor contributor to California’s agricultural economy.

Water is only one of the reasons. LA got an oil economy early, it developed a rich and complex urban economy, and as a result agriculture was displaced by other types of economic activity. But water is an important part of the story. Much of the region’s early agricultural economy was based on unsustainable levels of groundwater pumping. As William Blomquist documents in the sadly rare Dividing the Waters (for the short and far less expensive version, I talk about this in my book), a big part of what happened is an early realization of that unsustainability, and moves to adjudicate and manage the region’s groundwater basins.

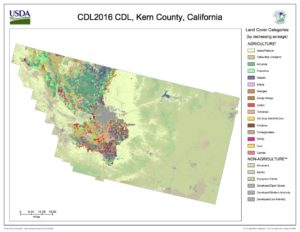

Kern County ag

In the evolution of California agriculture in the decades since, production greatly expanded in the state’s vast Central Valley. Kern County, at the heart of Central Valley ag, grew from 363,000 harvested acres in 1940 to 735,000 harvested acres in the 2012 Census. Accompanying the shift – unsustainable groundwater pumping.

It is inevitable, as Lois Henry reports in what is sadly her last water column for the Bakersfield Californian, that Kern’s irrigated acreage is going to decline. The proximate regulatory reason is California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (“SGMA”, and yes we pronounce it “sigma”). But the deeper reality is that there just isn’t the water down there to keep pumping groundwater the way we are now:

In the best-case scenario, Kern could lose 185,000 irrigated acres.

SGMA or not, irrigated acreage in Kern and other places like it is going to decline. The question is how we manage our trip down the glide path, which is why I am so sad Blomquist’s book is rare and out of print. It provides some great examples of managing that process well.

a note on methods:

One of my UNM Water Resources Program students has been asking me about my research methods. I have had a hard time providing useful answers because my methods are chaotic. That is unhelpful. So let me document them here for this particular case.

- I was reading my Twitter water list with my morning coffee, and saw a link to Lois Henry’s column.

- The column

- Seeing acreage for Kern County discussed in the column, I turned to the Census of Agriculture, which has piles of agricultural data at the level of U.S. counties.

- In the upper left box on the 2012 Census of Agriculture is a pull-down menu for older census publications. This takes you to the USDA Census of Agriculture’s historical archive, which is a treasure trove of old ag data. For me, a dangerous, deeply addictive, wondrous trove of old ag data.

- Ag data is water data. Water data is ag data.

- I already knew the LA County water<->ag story (sorry Tom, not sure yet how to help you with this “already knew” bit), so I pulled up the 1940-1945 data for comparison purposes.

- For the picture, I used the USDA’s Cropscape tool