tl;dr Western water policy and politics has to come to grips with the fact that overall water use is declining, not rising, as populations and economies grow.

The longer version….

Two years ago, when I was deeply immersed in the act of writing my book, I had an incredibly important conversation with Emily Turner, my Island Press editor. I’d been sending her draft chapters and, in the way of the best editors, she offered a gentle insight into something I was doing that I hadn’t seen myself.

One of the keys to successful communication, in any form or forum, is to try your hardest to understand what the people you’re communicating with already know or think about the topic at hand. What Emily saw me doing, without realizing I was doing it, was repeatedly addressing the beliefs/ideas/expectations I expected my audience to hold – starting with what they knew or believed and heading off from there into new territory. Over and over, she saw me debunking what I thought were myths.

My very particular memory of that conversation includes an embarrassingly theatrical detail of where it took place – sitting in a room at the Planet Hollywood mega-casino/hotel in Las Vegas, looking out the window at the fountains of the Bellagio. The myth was that Las Vegas was on an inevitable trajectory to outgrow its water supply. The reality was the conservation was more than offsetting population growth, with no end of either trend in sight.

Here’s how that ended up looking in my book:

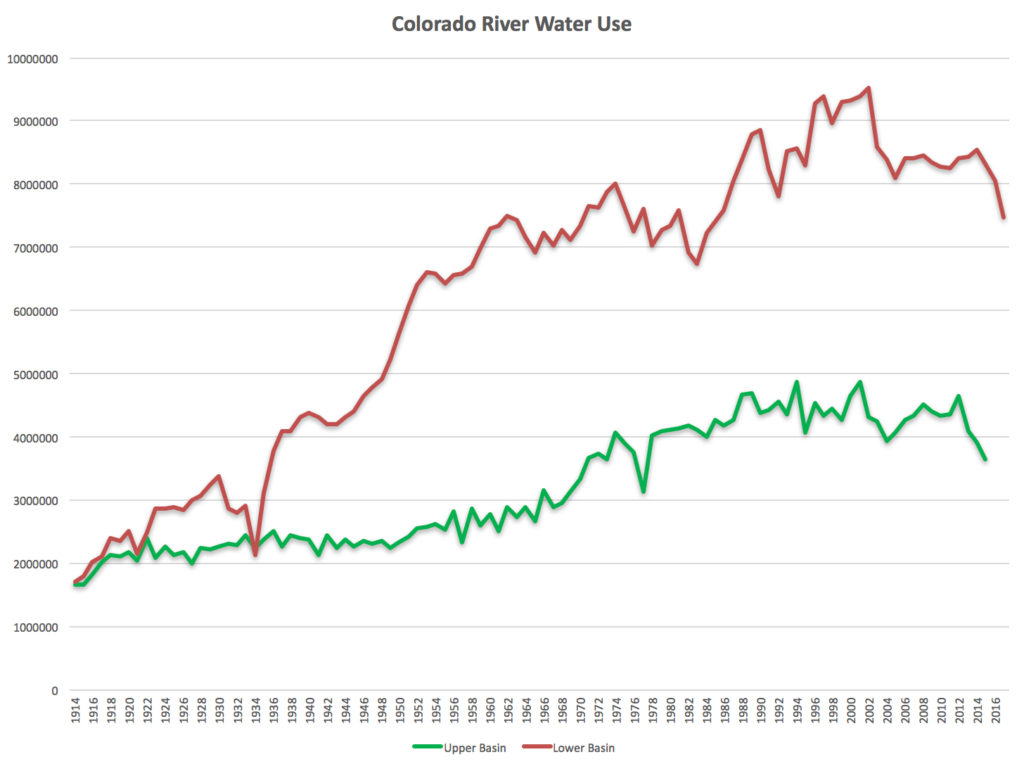

Despite the rhetoric of imminent doom, the math is inescapable. From 2002 to 2013, the greater Las Vegas metro area grew by 34 percent to a population of more than 2 million people. During that same period, its use of Colorado River water—its primary source of supply—dropped by 26 percent.

Las Vegas was not a cherry-picked exception here. I chose it carefully as a case study for my book because it is representative of what is happening across the West.

The year since the book came out has been a remarkable experience, as I’ve traveled the West watching my ideas interact with the world. In dozens of public talks, I’ve had a similar experience – I throw up a few slides with graphs of the decline of water use in Las Vegas, and Phoenix, and Albuquerque, and Las Vegas, and Phoenix, and Yuma, and Imperial, even as population and economic productivity grow – and the common response is, “Wow, really?” Followed by the questions. The most common audiences have been water wonks, but these discussions often (as often as I can make them) include water-concerned non-wonks as well.

I was thinking about this challenge this morning when I read this in an otherwise great blog post from Michael Campana. He’s quoting here an anonymous correspondent, someone who obviously has thought a lot, and well, writing him about groundwater science and policy in New Mexico:

Water consumption will increase as long as populations and development increase, but water resources are finite. It is inevitable that demand will exceed supply at some point. To approach and manage that point in a sensible and equitable manner will require reliable data. Long term data collection is needed to establish a historical baseline and emerging trends.

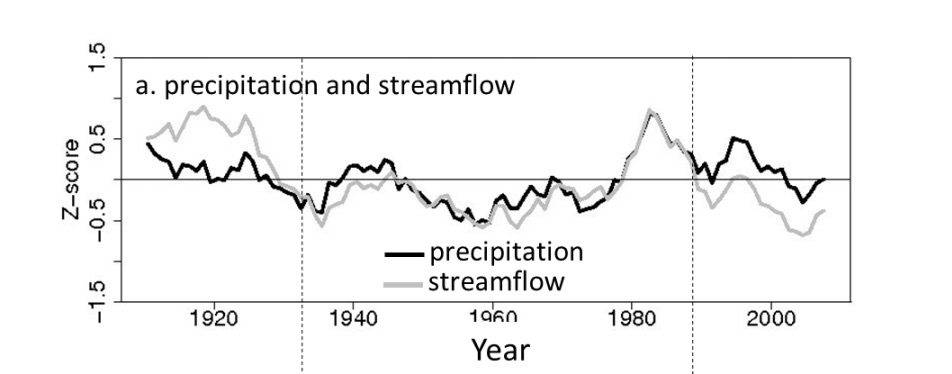

Yes, long term data is needed to understand trends, to make the best use of science to inform policy decisions about water. But one of the critical pieces of this is the need to understand that the data clearly points to the fact that water use is going down. In New Mexico, from whence Michael’s correspondent writes, water use peaked in 1995, according to the terrific USGS Water Use in the United States datasets.

In response to my decoupling spiel, I have become accustomed to many common whadabouts:

- What about this particular geography (say, for example, rural groundwater pumping in the southern San Joaquin Valley), or this particular category of water use?

- What about St. George Utah? Isn’t their water use going up even as they want to take more water out of the Colorado River?

- Yeah, but how long can that continue? Won’t conservation bottom out?

- What about climate change? Won’t that continue to reduce available water supplies?

- What about the non-rich parts of the world?

My answer to the whadabouts is generally, “Yup, that’s an important question.” Most do not yet have good answers. But it’s important to consider those as genuine questions, to be studied as we look at future water policy, not as reasons to simply ignore decoupling and continue to assert that water consumption will inevitably increase as long as populations and development increase.

Maybe in the long run they will, but that’s the question we have to ask, not an answer we can just assume.