The notion of a White Christmas is at best an inventive fiction, at worst a lie. Jody Rosen, in the wonderful book White Christmas: The Story of an American Song, put it thus:

The longing for Christmas snowfall, now keenly felt everywhere from New Hampshire to New Guinea, seems to have originated with Berlin’s song.

Albuquerque’s weather nerds have been playing the “consecutive days without measurable precipitation” game with increasing gusto in recent weeks. It’s up to 79 this morning, this Christmas Eve, which earned it a spot in the top ten such streaks since settler culture brought its particular empirical approach to keeping weather records to this land in the 1890s.

Whether this particular tool kit – a big funnel-like device out at the airport that captures and calculates bulk properties of the drops of rain or flakes of snow that fall upon it – is the best way to understand our current predicament is questionable. But the tools we use to understand our world bias that understanding in unknowable ways, and it’s the tool I know, so every morning I check the length of the streak and tweet.

Washington, D.C. Greyhound bus terminal on the day before Christmas, 1941. John Vachon, FSA/Office of War Information

During my newspaper career, I invented an Albuquerque Journal tradition of the White Christmas story and stuck to it, year after year, because editors are always antsy at this time of year. Antsy editors, in need of copy to fill newspapers, are an opportunity not to be missed.

One of my journalism tricks, in general, was to plant my story in familiar ground, starting with things I imagined readers knew and then lead them from there to new places. And there are few bits of ground as familiar to the American ear than Irving Berlin’s White Christmas:

The sun is shining, the grass is green

The orange and palm trees sway

There’s never been such a day

In Beverly Hills, LA

But it’s December the 24th

And I’m longing to be up north

Wait, what?

The canonical version, the hit sung by Bing Crosby and released in 1942 during the terrifying first year of American involvement in that war, leaves out that first verse. In so doing it leaves aside the tension of a complicated nation with oranges and palm trees and a culture drifted apart from an imagined and, as Rosen argues, never-quite-real past of sleighs and such on a Connecticut farm at Christmas.

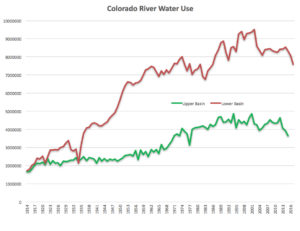

But the first verse is always what has charmed me, a life-long resident of the nation’s arid southwestern corner. And so, insulated by reservoir storage, aquifers, and plumbing from any real discomfort associated with 79 days and counting without any rain or snow, I can play the White Christmas game.