Rio Grande, Albuquerque, New Mexico, Oct. 20, 2017

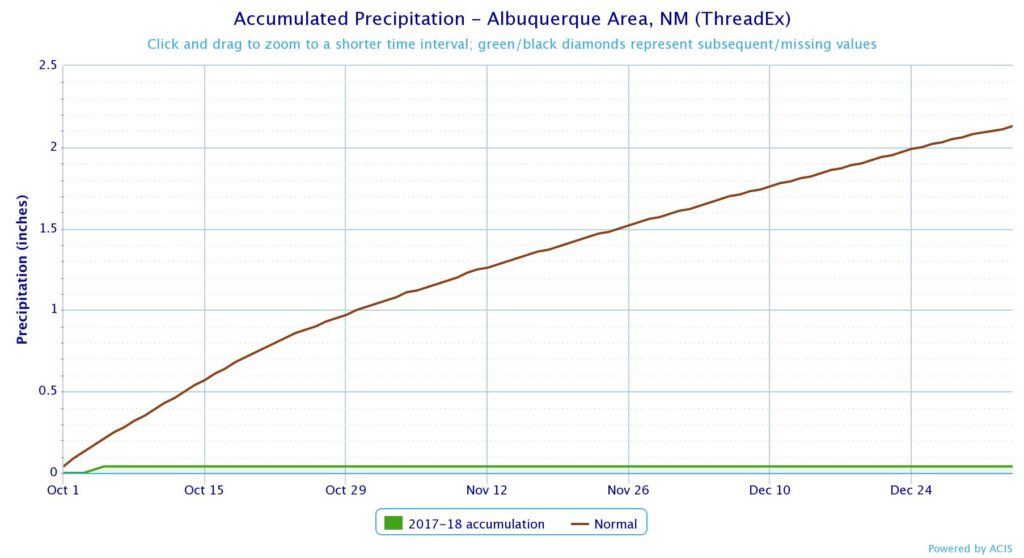

We’re up to 82 consecutive days without measurable precipitation at the Albuquerque airport, the 8th longest dry streak in more than a century of record keeping. And there’s nothing in the forecast out seven days, which is as far as it’s reliable to take it (butterfly effect and all). But OK, since you asked, the first glimmer of hope in the really-long-range-don’t-trust-them-but-this-is-just-a-blog-post forecast is Jan. 8., which would put this in the top five dry streaks on record.

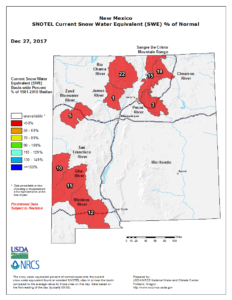

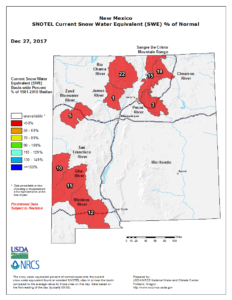

New Mexico snowpack, or lack thereof

Through yesterday, 2017 was tied for the warmest year on record in Albuquerque.

Snowpack in the northern mountains – important for water supply in the coming year – is lousy. The current regression forecast (an automated tool run by the NRCS to provide daily updates based on current snowpack) is just 34 percent of average runoff on the Rio Grande through central New Mexico. You shouldn’t stake a whole lot on forecasts done this early in the year (think of them as more like suggested possibilities – for the stats nerds the forecast at this time of year has an r squared value of 0.45) but neither should they be ignored. Every additional dry day makes it that much harder to catch up.

That said, however, we’re in remarkably good shape right now, the result of both a very good 2017, and significant water conservation and management efforts that leave our human water supply systems in decent shape to weather a bad snowpack.

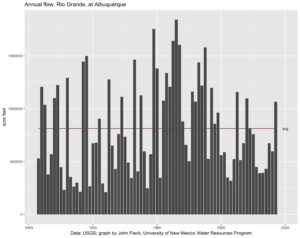

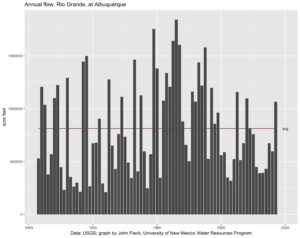

Rio Grande runoff, 2017

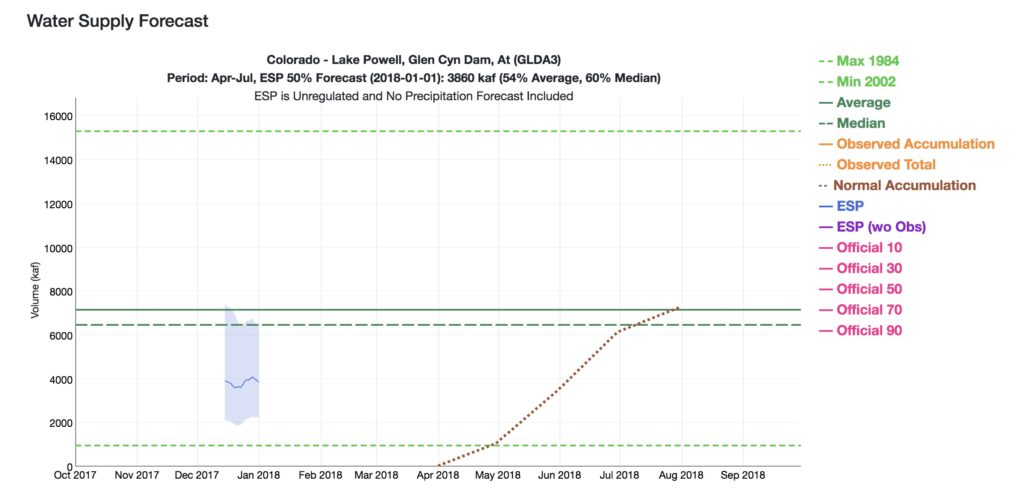

2017 runoff on the Rio Grande was outstanding – more than a million acre feet of water flowed past the Albuquerque gauge, beneath the Central Avenue bridge. But if you look at the graph to the left, you can also see how unusual a big runoff year is. This was only the third above-average year in the 21st century. “New normal” or whatever, this clearly requires an adjustment.

As a result of the big flow year, reservoir storage is in good shape. Elephant Butte, Abiquiu, El Vado, and Heron combined (the four primary reservoirs on the Rio Grande system in New Mexico) are up a combined ~300,000 acre feet over last year at this time. “Good shape” is relative here – Elephant Butte is still only 20 percent full, far from the glory days of the 1990s. But up is still up, and the Butte is up.

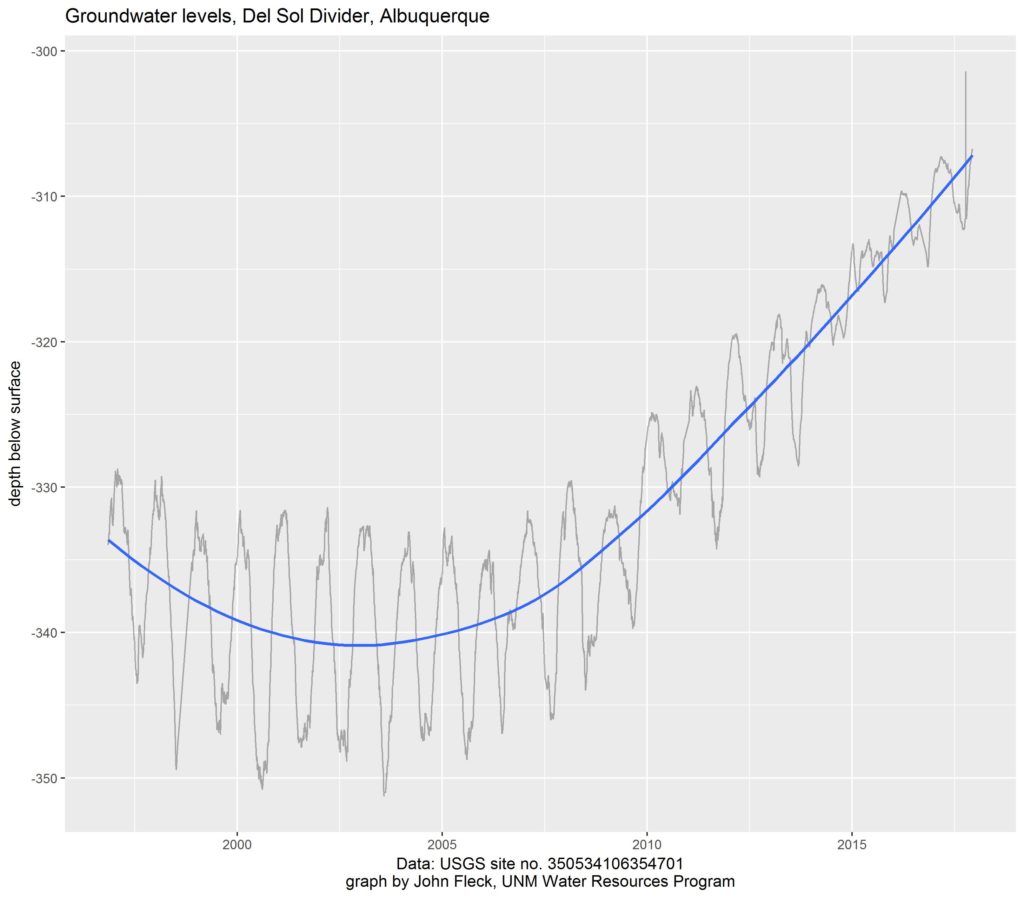

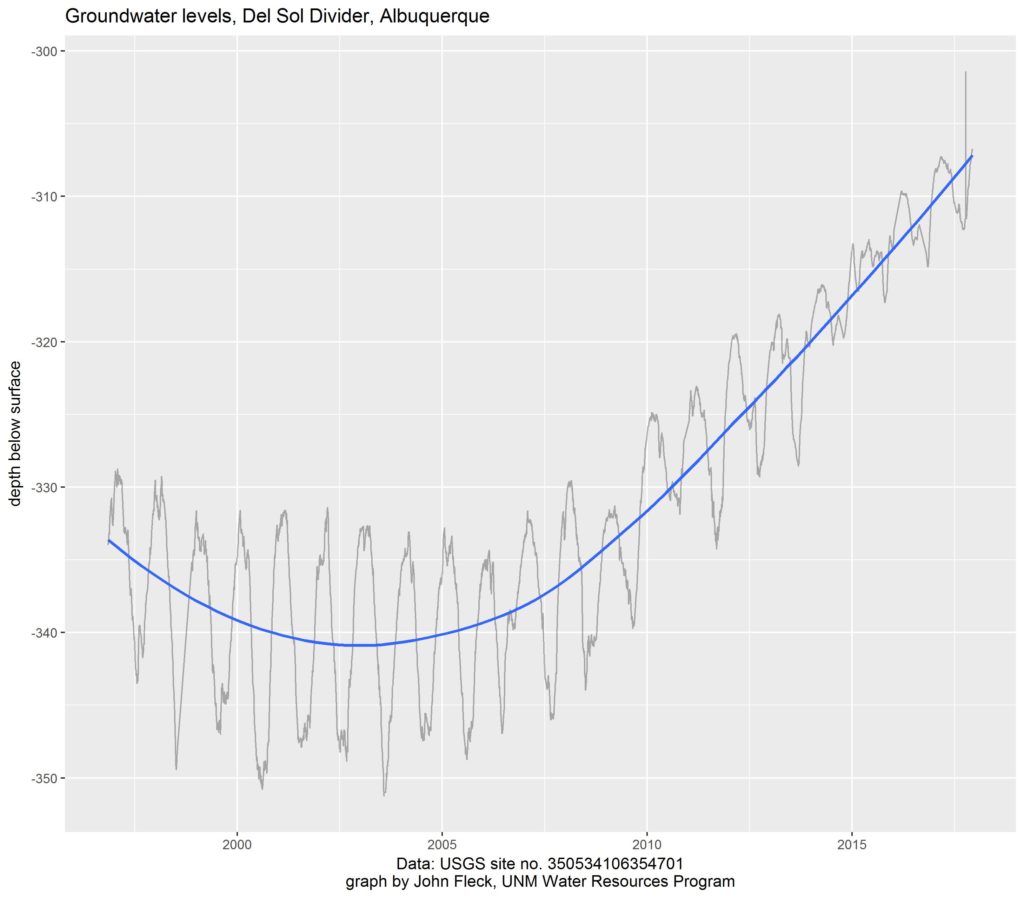

The most interesting thing, to me, is Albuquerque’s aquifer. This is the vast pool of water beneath the metro area, on which we’ve depended for much of the city’s modern life. A shift away from groundwater pumping to the use of surface water from the Colorado River Basin (via the San Juan-Chama Project), combined with significant conservation measures, have led to a rebound that seems unmatched among major urban aquifers in the western United States. Modeling done by the New Mexico Office of the State Engineer suggests aquifer storage is rising by 20,000 acre feet or more a year. Beneath my house, it’s risen more than 30 feet since our 2008 water management shift began.

Albuquerque’s rising aquifer

But that’s the human part. With reservoirs and aquifers and pipes and pumps, the humans will do OK even in the driest of 2018s. The natural systems, not so much. Expect low flows on the Rio Grande to make life very tough for the fish and riparian ecosystem. A year as dry as this is very tough on our mountain forests. And rangeland, whether for natural critters or grazing cattle, could have a very tough year.