The central challenge on the Colorado River

I’ve been thinking about the central communication challenge as we face down yet another dry year amid the continued drumbeat of Upper Basin talk about finding new ways to take more water out of the Colorado River.

It goes back to something I wrote in my book:

Within the network of state and water-agency representatives working on Colorado River Basin problems, there is a clear recognition that eventually some sort of “grand bargain” will be needed that finds a way to reduce everyone’s water allocation. To keep the system from crashing, everyone will have to give something up. But each of the participants in that core network also understands the dilemma that follows: each must then go home and sell the deal in a domestic political environment that views the river’s paper water allocations as a God-given right.

I’m not sure that’s quite right in a couple of ways. First is the assertion of that the solution is some sort of “grand bargain”. In the two years since I handed off the manuscript for Water is for Fighting Over: and Other Myths about Water in the West to my editor Emily Turner at Island Press, I’ve come to a better understanding of the nature and value of incrementalism on the river – deals done from the bottom up, one irrigation district and municipality at a time, rather than the sort of top down solution the “grand bargain” phrase implies.

But my underlying point – that there is an understanding gap between people who work at the basin scale and those who use water at the local level – seems even more relevant to me today.

The Colorado is really just a 15 million acre foot a year river

The second weakness in that passage of the book is my assertion that everyone in “the network” really understands this dilemma – that the Colorado River Compact and the federal legislation and treaty that followed allocated 18 million feet of a 15 million acre foot river. I still want to think that everyone in that core group I describe in my book understands this, but there is a strong push from the people one layer removed in water governance – the city councils and irrigation district boards and state legislatures across the basin – to grab hold now of the water promised in the Law of the River. That provides a strong incentive for some of the people in the core network to avoid pursuit of grand bargains and honest recognition that it’s really just a 15 million acre foot river.

Decoupling is real

This problem is connected to a second, which has been the thing that most surprised me as I’ve traveled the West talking water since the book came out. People are often surprised by, and sometimes actually resistant to, the evidence for decoupling – the evidence that we’re actually using less water now, and that we’ve demonstrated communities’ ability to grow and thrive even as their supply of water has shrunk.

Repeat after me

Those of you who read my newspaper work over the years may have snapped to my schtick – saying the same thing over and over. I dressed it up in different outer garments, but my core messages were generally the same. I believe in the power of repetition.

So let me reiterate two points for emphasis:

- The estimated natural flow at Lee Ferry on the Colorado River in the 21st century has been 12.4 million acre feet per year.

- This is not an 18 million acre foot river.

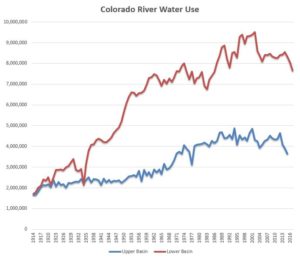

- Upper Basin water use in 2015, the most recent year for which we have data, was 3.7 million acre feet, the lowest since 1977. Lower Basin water use in 2017 (again the most recent year for which we have data, LB accounting is done more quickly) was 6.8 million acre feet, the lowest since 1987.

- Decoupling is real.

Seems I may have buried the lead here, or “lede” as my annoying journalist friends insist on spelling it.

#tbt to that time New Mexico tried to demand a Gila River Compact

For today’s #tbt (Throwback Thursday), a return to the remarkable era of Steve Reynolds in New Mexico water management, and that time Reynolds tried to give New Mexico an effective veto over the Central Arizona Project.

Students in this year’s UNM Water Resources Program spring class are doing a case study this year on New Mexico’s bit of the Gila, a Colorado River tributary that begins with the meager snow that falls in the mountains of southwestern New Mexico. So I’ve been reading so I have smart and/or fun things to say during class. Mostly fun so far, the Gila’s complicated, I don’t feel smart yet.

Back in the mid-1960s, Arizona was trying to win congressional support for the legislation needed to build the Central Arizona Project, its big straw to suck water out of the Colorado for Phoenix, Tucson, and parts there around. That took support from New Mexico’s congressional delegation, in particular the powerful Clinton P. Anderson. Anderson turned to our then state engineer, Steve Reynolds, to draw up the specifics of our ask. Reynolds said we needed Hooker Dam, a dam on the Gila as it flows out of New Mexico that had been on the reclamation community’s grand wish lists since at least 1946.

He also demanded (I toyed with “asked for” in this sentence, buy hey, it was Steve Reynolds, I’m guessing “demanded” more accurately captures the flavor of 1960s-era Steve Reynolds water governance) that the Central Arizona Project not be built until New Mexico and Arizona had negotiated a Gila River Compact.

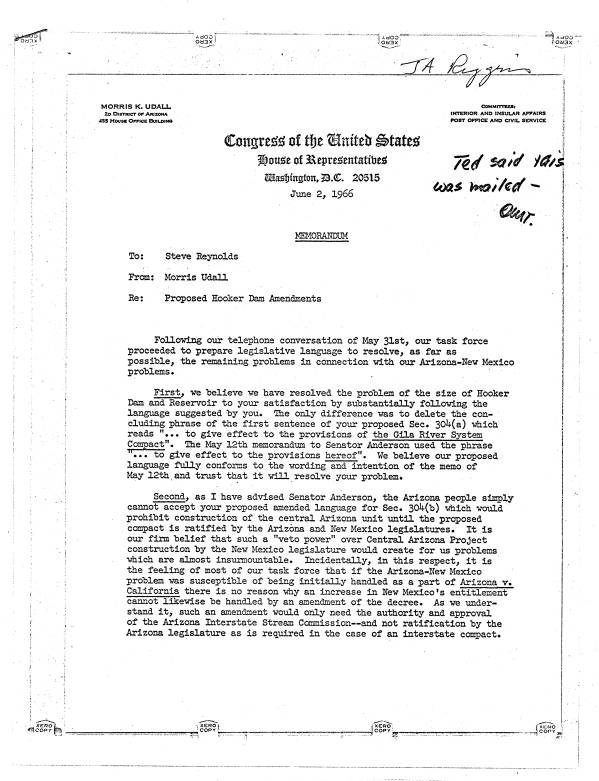

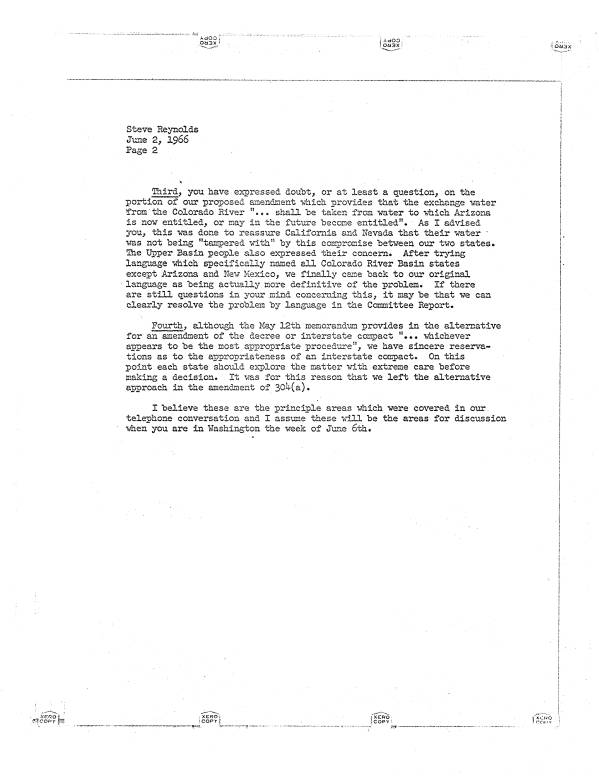

Mo Udall, Arizona’s 2nd District congressman and one of the state’s leads in the negotiations, was happy to put the Hooker Dam language in the proposed legislation, but the demand for a compact was full stop. Any compact would require the approval of the New Mexico legislature, which was a balance of power pill too hard for Arizona to swallow. “It is our belief that such a ‘veto power’ over Central Arizona Project construction by the New Mexico legislature would create for us problems which are almost insurmountable.”

We didn’t get a compact. And they never built Hooker Dam.

Here, via the Western Waters Digital Library, is Udall’s letter:

What Did We Know and When Did We Know It: How Much Water Does the Colorado River Really Have?

I’ll be yammering in public Thursday in Albuquerque, y’all should come!

What Did We Know and When Did We Know It:

How Much Water Does the Colorado River Really Have?In retrospect, it is clear that the 1922 Colorado River Compact was negotiated during a

historically wet period, and that as a result the agreement allocated more water than the river could actually provide in the long term, leaving problems that remain unresolved today. But what was the state of the hydrologic and paleohydrologic science at the time? Was the information available to make better decisions if the negotiators had chosen to use it? The story of the relationship between science and decision-making on the Colorado River in the 1920s, and in the decades that followed, offers important lessons for coping with the challenge of managing water in the arid Southwest today.

This is the monthly AWWA/RMWEA luncheon, anyone can come just show up:

Le Peep Restaurant

4921 Jefferson St. NE

(South of intersection of I?25 & Jefferson NE)

No RSVP or Fee Required

Attendee Pays for Own Lunch

Thursday Jan. 18, 2018

11:30 ? 1:00 p.m.

Order food at 11:30; technical program starts at 12 noon.

You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave

The palm tree as we know it is, for all practical purposes, non-native to Southern California. It requires a great deal of water, which is generally imported.

Last week I noted the disturbing analogy of 1976-77 for the Colorado River Basin, a year eerily similar in the early months of snowpack development to 2017-18.

In addition to the major drops in reservoir levels, 1976-77 produced four of the eight best-selling albums of all time:

- Meat Loaf: Bat Out of Hell

- The Eagles: Greatest Hits (1971-75)

- Fleetwod Mac: Rumours

- The Bee Gees and others: Saturday Night Fever

Also, Frank Zappa appeared in December 1976 on Saturday Night Live. Zappa played Peaches En Regalia from his album Hot Rats, which did not sell as well as Bat Out of Hell and the others but was not without its charms.

Initial forecast: Lakes Mead and Powell headed for record low in 2018

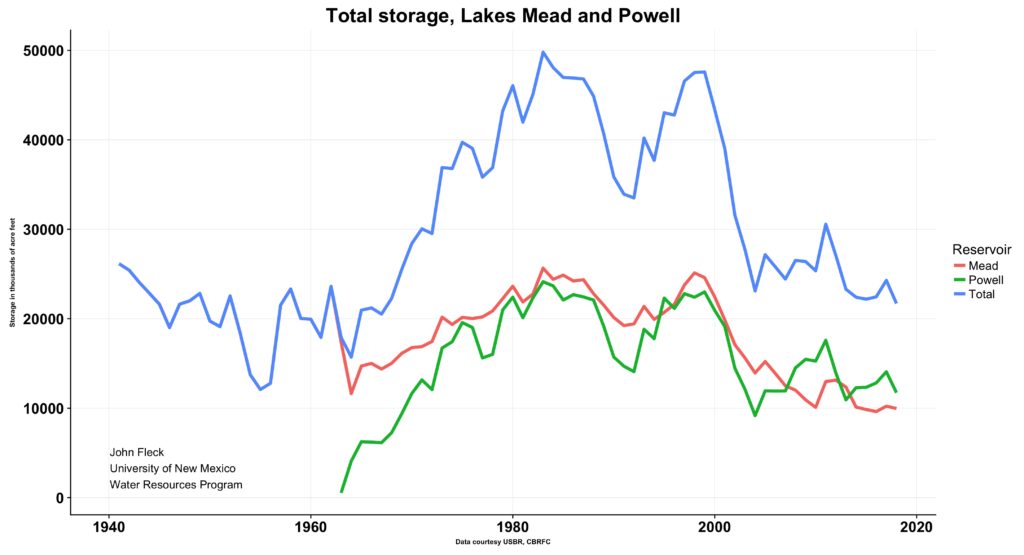

With an underwhelming snowpack right now, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s initial 2018 forecast (pdf here) projects combined storage in Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the two primary reservoirs on the Colorado River, will drop to 21.7 million acre feet by the end of 2018. That would be the lowest Mead/Powell combined year end storage since Powell was first filled in the 1960s.

WARNING: Just this afternoon, I was discussing reservoir storage data with some folks working on Colorado River policy analysis and I strongly discouraged using the 2018 forecast yet. It’s early. It could snow a lot. It also could not snow a lot. The error bars on a forecast made in January are huge, it will almost certainly change in one direction or the other. But for what it’s worth, here’s my updated combined storage graph with the 2018 forecast added.

There’s still enough water in storage to prevent a 2019 Lower Basin shortage declaration. But the risk for 2020 is rising.

It finally rained in Albuquerque

It finally rained yesterday morning in Albuquerque, a bit after 8 a.m., ending a 96-day dry streak.

The water in the bottom of my gauge looked like strong tea as the rain washed out three months’ dust, and the relief was not measurable, but large. I ended up with 0.09 inch (2.3 mm) at my house, and the Albuquerque airport gauge run by the National Weather Service got 0.03 inch (0.8 mm).

But….

My skin is cracking, and conversation at the office this week turned to moisturizing techniques. Since Oct. 1, the “water year”, 2017-18 is the third driest year in more than a century of records here, a ranking that only changed slightly among years that, for all practical purposes, saw no meaningful rain on the landscape this far into the winter season.

In my morning paper Kerry Jones (NWS meteorologist, graduate of UNM’s Water Resources Program, skilled communicator of such things) gave these “yeah buts”:

“We would need unprecedented wetness, almost equivalent to the dryness we have experienced, to make up the ground we have lost,” he said.

On the need for federal legislation to implement Colorado River drought plans

Eric Kuhn* of the Colorado River District wrote an interesting memo (pdf here) for his board’s meeting next week that lays out the options and reasoning behind current discussions about whether federal legislation will be needed to implement Colorado River Basin drought plans.

The “Law of the River”, which governs allocation, distribution, and management of the Colorado’s water is an interlocking body of statute, compact, treaty, court decision, and executive branch actions that makes tweaks tricky. If you want to do something in one part of the law – say, for example, adjust allocations to respond to drought – you have to be mindful of the impact it has on other areas of the law, even if everyone’s in agreement on the steps to be taken.

At last month’s Colorado River Water Users Association meeting, there was an interesting discussion (during a panel moderated by Eric) of whether federal legislation is needed to implement the various institutional widgets being developed under the rubric of the “Drought Contingency Plan(s)”.

There is a general consensus that legislation will be needed for the Lower Basin part of the DCP, which sets new guidelines for reducing water deliveries from Lake Mead to California, Nevada, and Arizona under conditions of Lake Mead emptiness. Here’s Eric:

This piece is relatively straightforward, and those favoring this approach say Congress can probably do this in a relatively straightforward, non-controversial way despite its current dysfunction. Simple stuff can still get done.

But there are other layers of complexity, including the question of whether, once we unlock the Congressional Action on the Colorado River box, we should take the opportunity to put other stuff in it. Maybe, for example, the states of the Upper Basin should ask for legislation creating a more flexible framework for operating Upper Basin reservoirs to ensure we keep enough water in Lake Powell to avoid compact delivery problems. Eric, in his board member, argues for caution in this regard:

* Disclosure: Eric and I are collaborating on a book.

What happened in the Colorado River Basin in the winter of 1976-77?

At yesterday’s monthly Colorado Basin River Forecast Center briefing, Greg Smith noted, by way of analogy, the winter of 1976-77. Smith explained that he wasn’t forecasting – the fact that the evolution of this year’s forecast is similar to 1976-77 doesn’t mean that the rest of this year will be like that year, or that this year’s runoff will be like 1976-77. But picking analog years is a great communication tool, to give us a sense of what actually happened, historically, in conditions similar to those we might see today.

So let’s look at 1976-77.

- Naturalized inflow from the Upper Colorado River Basin at Lee Ferry was 5.4 million acre feet, the lowest in the USBR’s Natural Flow Database (which goes back to 1906)

- Lake Powell dropped 3.4 million acre feet, the fourth largest one-year drop since Glen Canyon Dam was built (1990, 2002, and 2013 had bigger drops)

- I graduated from high school

None of these are encouraging analogs.

Overcoming “use it or lose it” on the Colorado – an example

Yesterday I pointed out how much water is being stashed in Lake Mead as an example of how folks on the Colorado River are overcoming the old “use it or lose it” problem in western water.

Here’s another example, this time with water taken off of the river and stored underground, in this case excess water in Phoenix’s allocation being stored via a collaborative relationship with Tucson, which has big spreading basins and aquifer storage capability:

“This is Colorado River water that they can’t use today. But if they don’t use it, they don’t have it later in the future,” Molina said. “We worked out an agreement with them where they will store extra water in our recharge facilities at no cost to us.”

The key here is the creation of a new institutional arrangement – a Phoenix-Tucson water banking deal – to overcome a shortcoming in the existing institutional arrangement. Here’s the issue: Phoenix doesn’t currently use its full Colorado River allocation. Four years ago, it toyed with the idea of simply storing its unused allocation in Lake Mead. But that can’t happen, because rules. The rules proved difficult to change, so Phoenix and Tucson developed a side deal, inventing a new institutional widget that allowed them to accomplishment something quite similar under the existing rules.