New constraints on Imperial’s ability to throttle back Colorado River water use

I’ve been puzzling over the impact of Imperial Irrigation District’s legal struggle over its “Equitable Distribution Plan”, a regulatory framework for governing how much water individual farmers can use. This story from Daniel Rothberg is a big help:

As a practical matter, the repeal of the Equitable Distribution Plan lessened IID’s control over its plans to potentially store more Colorado River water in Lake Mead, which is a key part of California’s role in the Drought Contingency Plan.

“The absence of [an Equitable Distribution Plan] means that we lack a very important tool that has served us since 2013, and will certainly reverberate throughout the basin and among all the Colorado River water users,” Kevin Kelley, IID’s general manager, told the board on February 6….

Without the allocation system, IID’s water use is determined less by its elected board and the staff and more by the orders of agricultural users, which can vary. The ruling leaves the district with fewer management tools to control overruns and conservation.

Via Water Deeply, helpful throughout.

“breakdown” in Kirtland fuel spill cleanup

Albuquerque’s municipal water utility, in a strikingly worded memo yesterday, said the latest plans for managing a huge groundwater spill on and adjacent to Kirtland Air Force Base represent “a breakdown” in what was once a partnership among the water utility, the Air Force, and the New Mexico Environment Department.

The new plans back away from aggressive state-mandated efforts to clean up the spill, and weaken ongoing efforts to characterize the extent and seriousness of the contamination, according to the memo. According to the Water Utility, the new plans are “disconnected from the stated goal of protecting drinking water and the aquifer and undermine Water Authority’s ability to ensure the safety and quality of drinking water”:

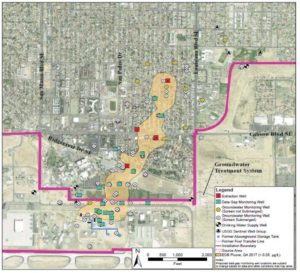

contaminated groundwater spreading beneath Albuquerque

The spill, discovered in 1999 but likely dating to the 1950s, came from a long slow leak in an Air Force aviation fuel pipeline adjacent to the base runways. As you can see from the map, it has spread nearly a mile off of the base, moving beneath a southeast Albuquerque neighborhood. Because of its proximity to Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority drinking water wells, it is by far New Mexico’s most serious groundwater contamination problem.

A tense relationship between the ABCWUA, the Air Force, and state regulators had thawed in 2012-13, as the New Mexico Environment Department and the Air Force invited the Water Utility into the decision-making process. But the new memo, from the Water Utility’s Rick Shean (a graduate of the UNM Water Resources Program!), confirms what I and others have been hearing for some months – that the relationship has broken down.

This poses interesting governance questions that I’ve used as a case study in my new academic life. The Water Utility does not have legal standing as a regulator here – that role falls to the New Mexico Environment Department. But the Water Utility, especially under the leadership of Bernalillo County Commissioner Maggie Hart Stebbins and Water Utility Chief Operations Officer John Stomp, plays a critical role in looking out for the interests of the community. We made significant progress after the Air Force and NMED invited ABCWUA into the decision-making tent.

This issue is on the agenda for tonight’s (Wed. March 21, 2018) ABCWUA board meeting. 5 p.m. at the Council Chambers, Albuquerque City Hall building.

Palo Verde Irrigation District withdraws lawsuit against Metropolitan Water District of Southern California

In a bit of Colorado River detente, the Palo Verde Irrigation District has filed a motion in Riverside County Superior Court to withdraw a lawsuit it had filed against the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California over the use of water on Met-owned land in the Palo Verde District:

The move does not mean peace on the river between these two powerful water agencies, but it does at least create space for discussions, including a meeting scheduled for next Monday between leaders of the two organizations.

PVID filed the suit last year over its concerns about what Met was doing on land the municipal water agency owns in the rural agricultural district. PVID has been increasingly concerned that Met will scale back farming in the desert valley to send the saved water to folks in urban, coastal California. Met has repeatedly try to assure the Palo Verde community that its intention is to collaborate and support continued farming.

The suit was a minor legal skirmish, over California Environmental Quality Act issues rather than the underlying water rights and management questions – more of a shot by PVID across Met’s bow. The concerns at the heart of the dispute have not gone away, but will now be addressed in meetings and negotiation rather than litigation.

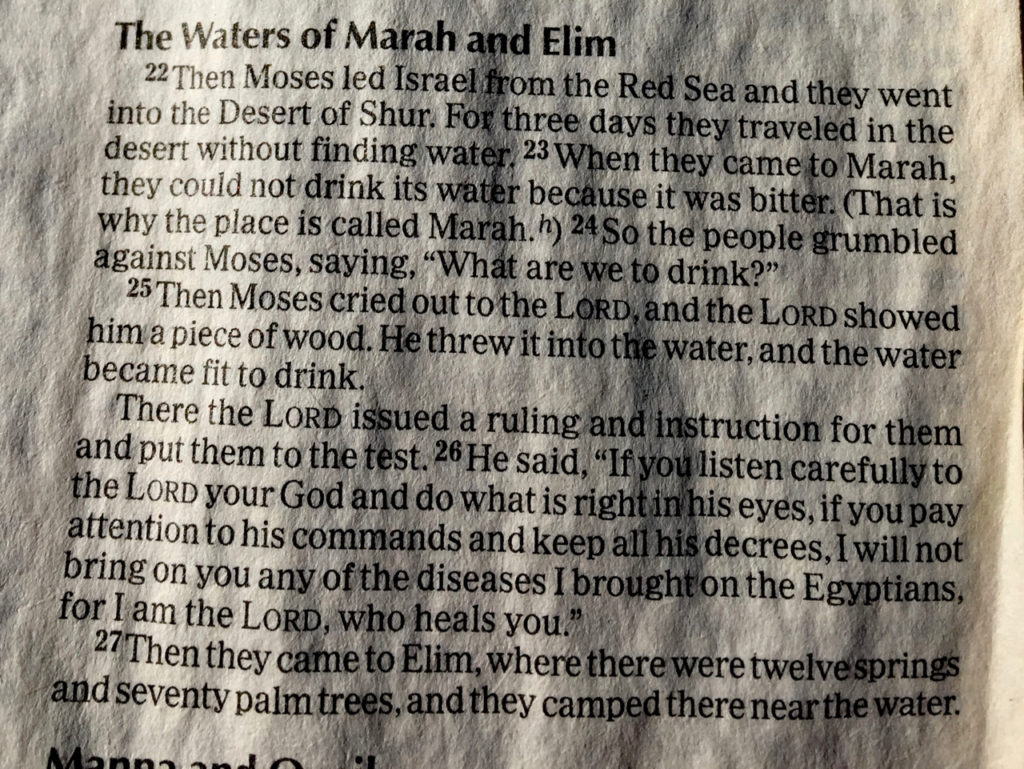

“For three days they traveled in the desert without finding water.”

On a bike ride this morning, I turned onto a little dirt trail through the woods, heading out toward the Rio Grande. Twenty yards from the river, I found a book lying in the trail, battered by the weather:

The book, later.

It was a Bible, lying open to Exodus 15:22: “Then Moses led Israel from the Red Sea and they went into the Desert of Shur. For three days they traveled in the desert without finding water.”

“When they came to Marah, they could not drink its water because it was bitter.”

Not sure what to make of this, other than to point out that the river is low, but they did eventually get to Elim:

Then they came to Elim, where there were twelve springs and seventy palm trees, and they camped there near the water.

I left it on the bench, with a stick to mark the page.

Water policy implications of elk, raiding wheat fields, in Polvadera, New Mexico

I had one of those “I wish I was still a reporter” moments when Glen Duggins, at yesterday’s meeting of the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District board meeting, raised the issue of elk in Polvadera.

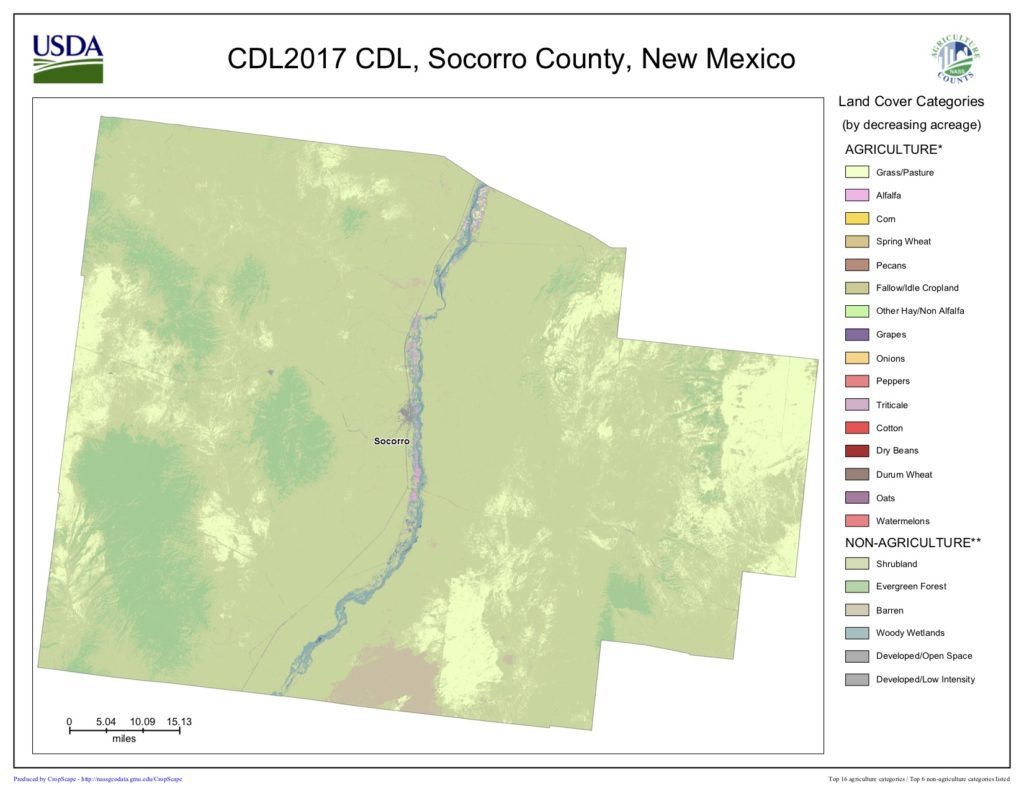

Polvadera is an unincorporated community along the Rio Grande, between the also unincorporated communities of San Acacia and Lemitar, strung out along the floor of the most productive farmland along this stretch of the river. Calling it “the most productive farmland” may be misleading, because the net cash farm income along this stretch of the river tends to be negative save for Socorro County. But this is not Iowa, and the sort of ag productivity numbers that shape the CBOT futures markets can’t tell us the full story of farming here. Which is why I perked up at the discussion of elk.

Duggins, a board member from Socorro County, had gotten a call from a constituent who was having trouble with elk raiding his wheat field. This is not large-scale agriculture we’re talking about. And the MRGCD is an irrigation, drainage, and flood control agency, not a game management agency. But the fact that it’s a very small farmer growing six acres of winter wheat to supplement his retirement income in some sense makes it all the more important, and sheds interesting light on questions of what water management and governance are really all about here in what we in New Mexico call “the middle Rio Grande valley”.

In my last job, as a newspaper reporter, I used to hang out at the MRGCD’s Monday afternoon board meetings when I could. It turns out that in my new job, as director of the University of New Mexico Water Resources Program, a couple of hours at the MRGCD board meeting also is time well spent. You get agency water manager David Gensler’s regular water reports – how much is in storage, when and where and how releases to the ditches for spring irrigation are progressing, and the important question in a dry year like this of how the summer season looks. Chuck DuMars, the former law professor who represents MRGCD (and many other important water agency clients, including California’s big Imperial Irrigation District), gives what often amounts to mini-seminars on the rich tapestry of New Mexico water law. Those are usually the main attractions for me.

But you also get governance at the retail level – complaints about which ditches are getting water when, the eternal discussion of ditch bank gates and public access, culvert repairs. And yesterday afternoon, elk.

Raids by elk onto the Socorro County valley floor have been an increasing problem over the last decades (yes, I wrote about this when I was at the newspaper – I’ve got links like this for many occasions!).

I am not a lawyer, but I’m pretty sure elk predation is not explicitly covered by MRGCD’s explicit statutory authorities. But in the midst of the hodgepodge of government entities whose duties encompass agriculture, MRGCD is arguably the most important. Socorro County’s human geography is defined by the narrow strip of green along the Rio Grande and the irrigation ditches that spread its water on the valley floor immediately surrounding it. The distribution of water both enables and constrains agriculture in all its forms in this part of the country, and therefore the place’s human habitation. So when the Polvadera farmer saw elk eating his supplemental retirement income, it was I guess natural to call Duggins. That is the importance of this story.

It’s not clear to me what a water agency can do about elk. But the MRGCD board’s Urban Affairs Committee pledged to look into it, there was a suggested field trip to check out the elk problem in person, and a charmingly lengthy discussion about ensuring that MRGCD staff with hunting experience and inclinations be included in the policy discussions of possible solutions to the Socorro County elk problem.

I love the pageant of democracy.

We should probably stop calling it “drought”

Colorado River Basin Managers are working on what they call a “Drought Contingency Plan” to reduce water use, but that’s probably a bad name to describe what’s going on, as the members of the Colorado River Research Group explain in a new white paper (pdf):

In current Colorado River water management, perhaps no word is used (and misused) more than drought. To most people, the word drought contains two concepts. The first is the lack of available water, primarily a function of below normal precipitation, but often exacerbated by management and water?use practices. Second is the notion that the condition is temporary—a deviation from a norm that is expected to eventually return. Aridity, in contrast, refers to a dryness that is permanent, and is a function of natural (and presumably stable) climatic conditions. While it is fair to say that the Colorado River Basin is in a period of drought (in that recent precipitation has lagged slightly below the long?term averages), and that much of the basin is arid (or semi?arid), neither term is adequate to accurately describe emerging conditions in the Colorado River Basin. For that, perhaps the best available term is aridification, which describes a period of transition to an increasingly water scarce environment—an evolving new baseline around which future extreme events (droughts and floods) will occur. Aridification, not drought, is the contingency that should guide the refinement of Colorado River management practices.

The underlying hydrologic problem is a decline in “runoff efficiency” – less water in the rivers for a given amount of rain or snow. That’s also the message in a new paper by the University of New Mexico’s Shaleene Chavarria and Dave Gutzler on the Rio Grande, where precipitation has actually gone up slightly, but river flows have nevertheless gone down.

Changes in the snowpack–runoff relationship are noticeable in hydrographs of mean monthly streamflow, but are most apparent in the changing ratios of precipitation (rain + snow, and SWE) to streamflow and in the declining fraction of runoff attributable to snowpack or winter precipitation.

So yeah, drought’s a less useful word. We don’t change language by publishing white papers and journal articles, but we can at least focus some energy on the conceptual problems.

Putting the water back

Laura Paskus on an encounter with Jennifer Pitt in the Colorado River Delta:

Walking through the cottonwood forest, Pitt says this landscape was destroyed before anyone figured out what to do about it. When the Colorado River started running dry in the mid-20th century, there weren’t yet environmental laws to temper or stop destructive operations or policies.

“We didn’t have a regulatory framework, we didn’t have courts, and we didn’t have any leverage,” Pitt says. “We figured that out at some point in the mid-2000s and figured out that as a conservation advocacy community our path forward had to be collaboration and cooperation. We had no choice….”

“The perspective on rivers that has allowed us, as a society, to manage them unsustainably—where our demands exceed supply, which has devastated the health of rivers—is also set up to devastate communities,” Pitt says. Fixing rivers means stabilizing water supplies for communities, both urban and rural. As water managers and stakeholders wrangle with policy, infrastructure and water uses and rights, they can also be deliberate about healthy rivers—or, she says, “remnants” of healthy rivers.

Unlike in the past, environmentalists and community advocates aren’t always on the outside, unable to apply the brakes to destructive projects or unsustainable policies, she says. And addressing climate change offers the chance to look at things differently, too.

“All those water management systems that seemed in the past so fossilized and unable to adapt to changing social values are now having to change because of climate change and the declining supply,” Pitt says. “As they’re revisiting the policy, which will change the infrastructure, which will change how water is distributed across economies and societies—now is the time for us to be at the table, helping to find the ways to at least not lose more, and in some cases, to try and rebuild.”

Florence Hawley Ellis

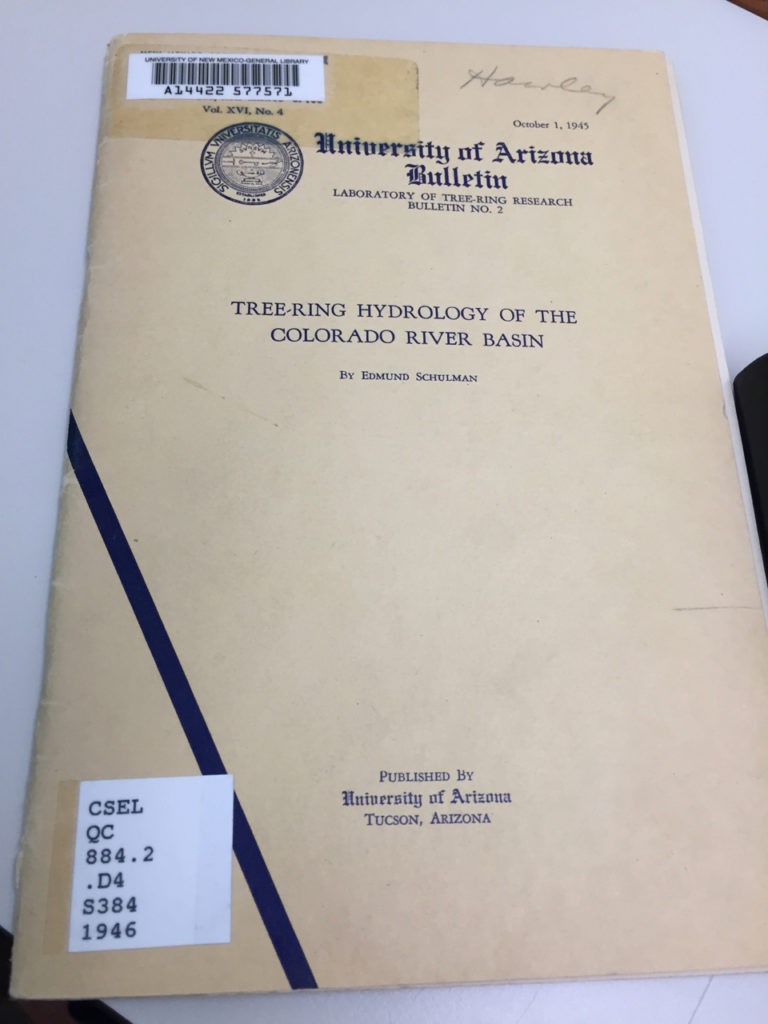

This afternoon I tweeted a picture of this treasure, found in the stacks of the University of New Mexico’s Centennial Science and Engineering Library:

Schulman E. Tree-ring hydrology of the Colorado River basin. University of Arizona; 1946.

Tom Swetnam, a friend who is the former director of the UofA Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, recognized the name in the top-right corner: “Looks like that may be Florence Hawley Ellis’ personal copy of Schulman’s classic. From UNM Library?”, with a link to this autobiographical sketch:

I have directed field schools for the Univ. of New Mexico: 1948, 1949, and for 3 seasons in the early 1950s at San Gabriel del Yungue at San Juan, for 5 seasons in the 1950s and ’60s at Sapawe near El Rito, in 1971 at Tsama on the Chama, and since then for Ghost Ranch a number of sessions in Gallina mountain sites and in 1975 and 1976 on Gallina village sites. Before directing field schools I worked with the Univ. of Ariz. in excavations in summers and then with the Univ. of New Mexico in the Chaco where I spent 11 seasons at tree-ring collecting and research, excavations, and directing laboratory work.

Schulman’s work is a treasure for other reasons.

For The New Project, Eric Kuhn and I are tracing the evolution of our scientific understanding of the hydrology of the Colorado River Basin, and Schulman’s 1946 LTRR report is a key milestone in the expansion of the toolkit from the stream gauge record to include paleo-hydrologic reconstructions using tree rings.

I think (commenters who know this literature please jump in) that this is the first published tree-ring reconstruction of the flow of the Colorado River, though Schulman and A.E. Douglass, the founder of the Tree-Ring Lab and basically the whole founder of the dendro thing period, had done unpublished work during World War II to try to help the war effort by clarifying the flow of the Colorado River and therefore the hydropower available for the war effort. And in fact there’s a reference in this monograph to some work Douglass published in 1936 that may have taken a preliminary stab at a Colorado River flow reconstruction. So more to come.

I’m particularly loving this dive into the literature because my first book was about tree rings, and it’s always been one of my favorite bits of science. That this particular copy of Schulman’s work belonged to Florence Hawley Ellis, a pioneer, as well, makes it doubly cool.

Do kids in greener neighborhoods grow up with bigger brains?

This is so far out of my area of expertise that I have no way of evaluating methodology or results, except to point out that it’s worth thinking about the water policy implications:

The Association between Lifelong Greenspace Exposure and 3-Dimensional Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Barcelona Schoolchildren

Lifelong exposure to greenness was positively associated with gray matter volume in the left and right prefrontal cortex and in the left premotor cortex and with white matter volume in the right prefrontal region, in the left premotor region, and in both cerebellar hemispheres. Some of these regions partly overlapped with regions associated with cognitive test scores (prefrontal cortex and cerebellar and premotor white matter), and peak volumes in these regions predicted better working memory and reduced inattentiveness.

It is at the very least another reminder that my longstanding enthusiasm for water “conservation” may be missing things.

Dadvand, Payam, et al. “The Association between Lifelong Greenspace Exposure and 3-Dimensional Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Barcelona Schoolchildren.” Environmental Health Perspectives 27012: 1.