As Arizona wrestles with the reality that its Colorado River supply as measured in actual wet water rather than the “paper water” doled out by the Law of the River, we’re getting a lesson in the difference between an “allocation” of Colorado River water and an “entitlement”. The place to watch this play out right now is in Pinal County, the stretch of rural desert dotted with cotton fields and alfalfa between Phoenix and Tucson.

We’re hearing a lot of talk coming out of Arizona about a collaborative effort to settle conflicts and move forward in the lead-up to a public meeting scheduled for Thursday (June 28, 2018) in Tempe. Bret Jaspers characterized what’s happening now as a “reboot” of the tortured relationship between the Arizona Department of Water Resources and the Central Arizona Water Conservation District, the agency that manages deliveries of Colorado River water to central Arizona.

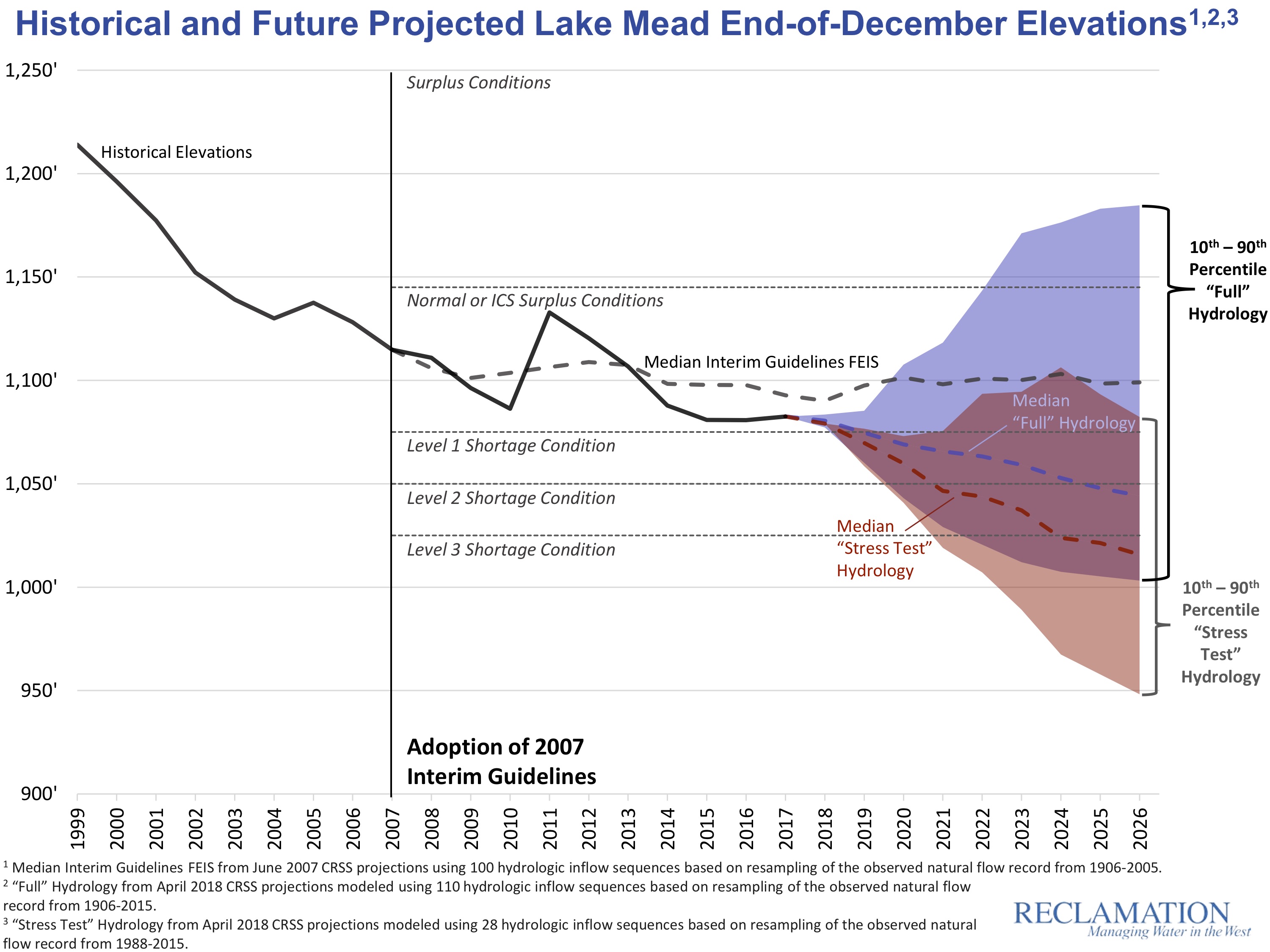

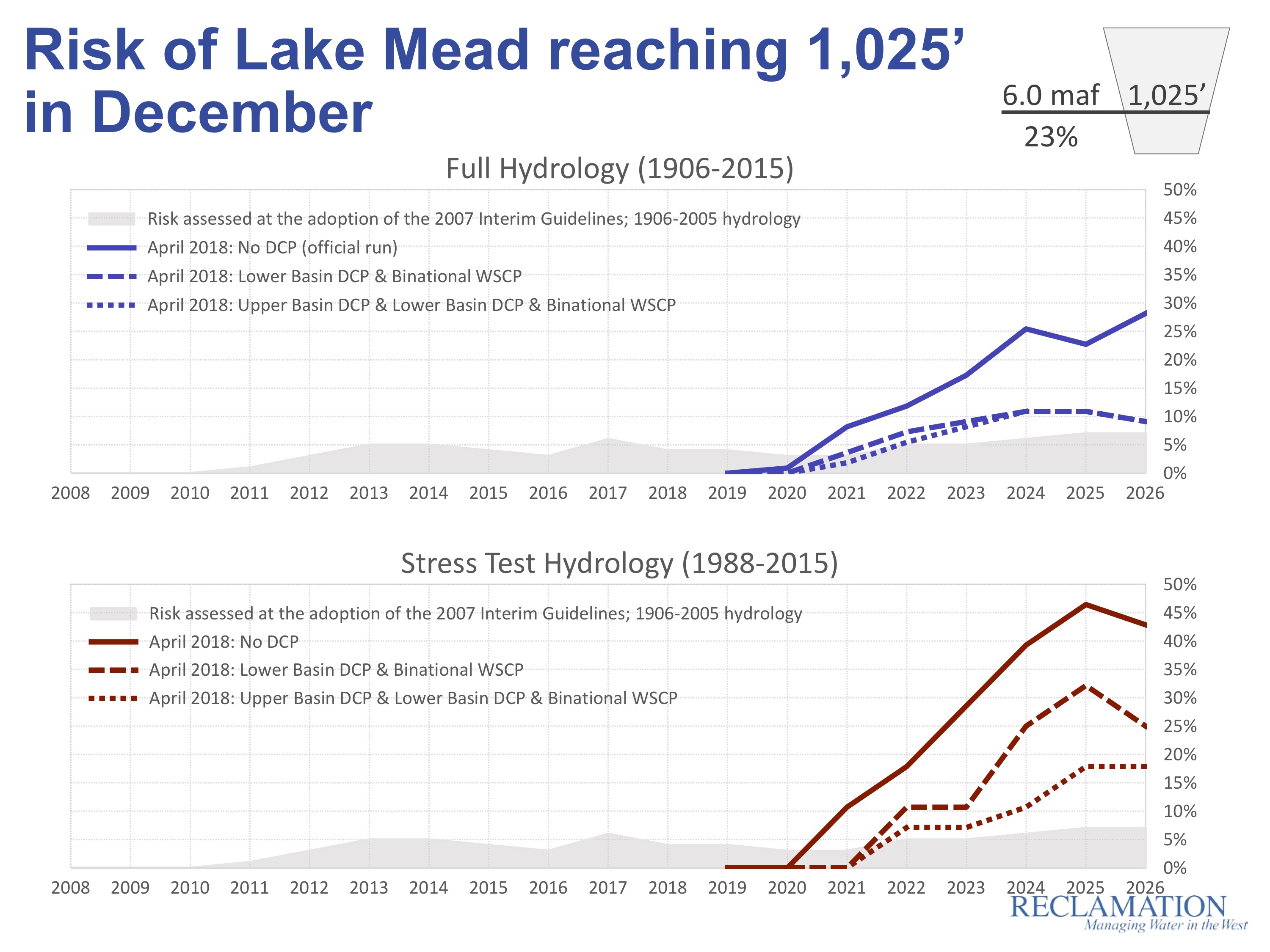

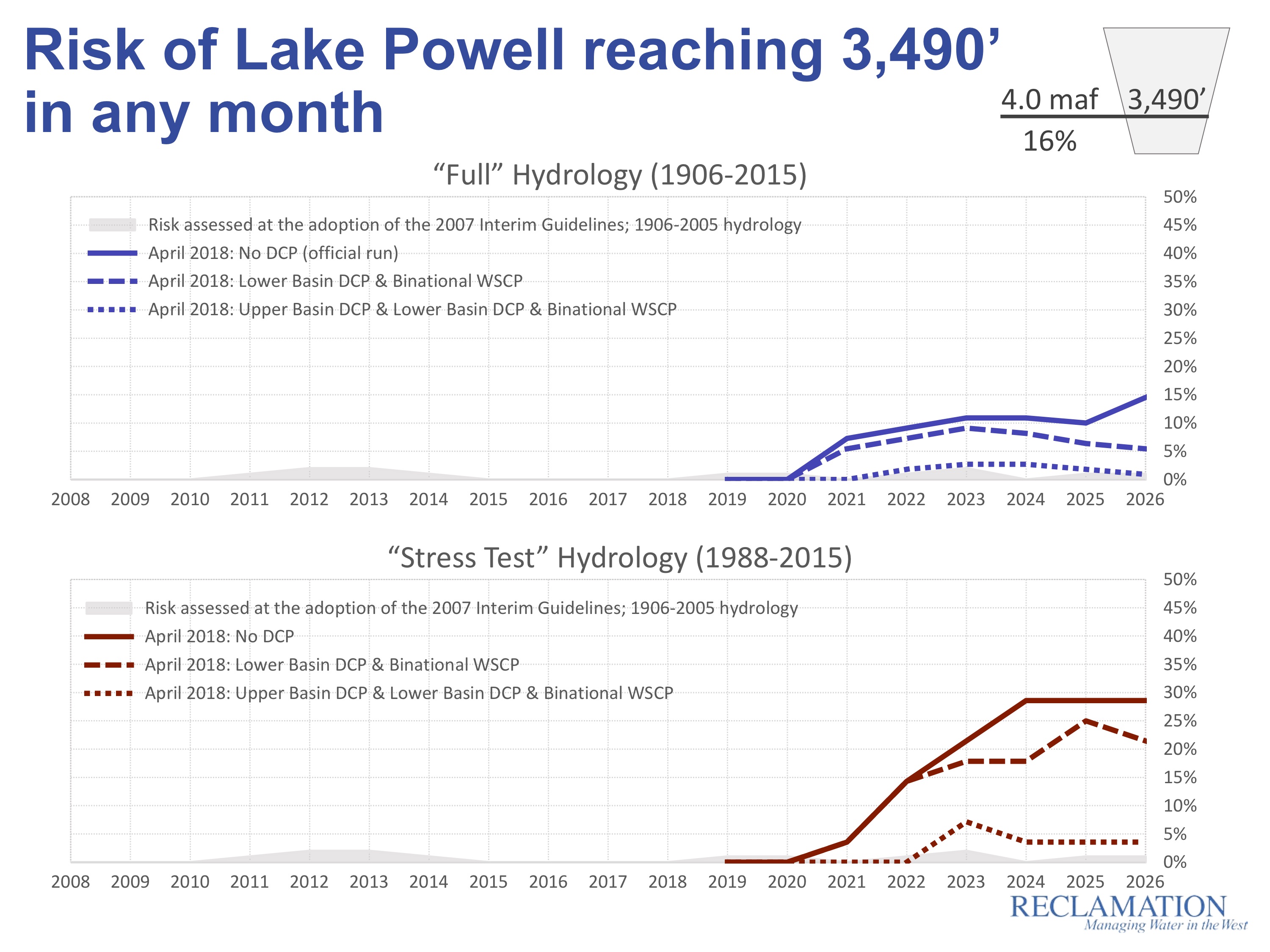

The meeting will be held in Tempe and live-streamed on the Internet. Commissioner of Reclamation Brenda Burman will be speaking to, in the words of the Arizona Department of Resources “discuss the risks to the system” which, as I wrote about a couple of days ago, involve crashing Lake Mead kinda soon.

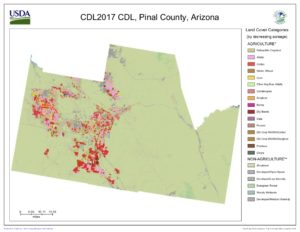

Courtesy USDA Cropscape. Red is cotton, pink is alfalfa

Pinal County is not exactly prime desert farming real estate, lacking the ready access to Colorado River water that you see in the valleys of Yuma, Imperial, Palo Verde, or on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. With little surface flow and an aquifer that cannot sustain farming in the long run, the only real alternative is imported Colorado River water via the Central Arizona Project, the canal that pumps water up from the Colorado River. But that is very expensive water, tough to afford without subsidy if you’re growing alfalfa and cotton.

And so subsidize we have (see this from Michael Hanemann for a history of CAP subsidies). Everybody’s irrigation water is subsidized in the West, but the Pinal County farmers’ water is subsidized a lot. Here’s how:

For the purpose of understanding Pinal County’s role in the current discussions, the key subsidy to look at is the deal signed by the counties’ ag interests in 2004 as part of the Arizona Water Settlements Act. Faced with high water costs even under the then-existing subsidy regime, the water districts signed a deal to essentially give up stronger water rights to free up water to meet Indian water rights settlement in return for yet more subsidy. Here’s how CAP explains it:

Irrigation districts that relinquished their long-term CAP entitlements under the terms of the Arizona Water Settlement Agreement were relieved of their federal distribution system debt—often referred to as 9(d) debt. In addition, CAWCD agreed to provide a pool of excess CAP water, subject to availability, to the relinquishing subcontractors at energy-only rates through 2030. This pool, referred to as the Agricultural Settlement Pool, was sized at 400,000 acre-feet initially, declining to 300,000 acre-feet in 2017 and then to 225,000 acre-feet in 2024. (emphasis added)

In return for what has been estimated at $343 million in subsidies since the deal was signed in 2004, the Pinal County farmers agreed to cheap water when it was available, but importantly this water was subject to availability. If water runs short, they’re among the first to see their supplies cut. The farmers were compensated in return for taking on greater risk. At least that’s the way the rules are written, and that’s the deal the farmers’ representatives cut, to the tune of about $25 million per year in subsidy – from the taxpayers of the greater Tucson-Phoenix area to the farmers of Pinal County to grow mostly cotton and alfalfa.

But the conversation right now, as Arizonans struggle with how to deal with shortage on the Colorado River, suggests that as that “subject to availability” shifts from the abstractions of white papers and legal documents to a risk of actual wet water cutbacks, thinking about the Pinal County farmers has shifted to treating that water as an allocation of water subject to availability based on the variability of the system (the way the classic structure of prior appropriations works) to an entitlement to a firm supply. The resulting discussions involve considering whether farmers should be compensated should supplies run low and they can’t get the water. Here’s the key bit from Bret Jaspers’ KJZZ piece last week, quoting Central Arizona Project general manager Ted Cooke:

One sticky subject is what to do about farmers in central Arizona, who would take a big hit under the current rules.

“How do we find a way to make things less painful for them?” Cooke asked. “Not completely painless, but less painful.”

This is not the only issue to be sorted before Arizona comes to terms on a Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan (or my new favorite moniker, a Use Less Water Plan – ULWP, pronounced “uhlp”). The Pinal bit is one piece of a deeper argument over who in Arizona gets to decide what happens to the state’s “excess” Colorado River water (an increasingly weird term).

But the fate of Pinal County farmers gets to the heart of our struggle to figure out how to live within a shrinking Colorado River supply.

Kightlinger’s right about the “uncharted territory” thing. The DCP is an effort to cobble together a map of the water management terrain ahead as we’re speeding toward – well, speeding toward something that we’re not quite sure what it is but it’s probably really bad.

Kightlinger’s right about the “uncharted territory” thing. The DCP is an effort to cobble together a map of the water management terrain ahead as we’re speeding toward – well, speeding toward something that we’re not quite sure what it is but it’s probably really bad.