By Eric Kuhn and John Fleck

With the Colorado River’s “Drought Contingency Plans” now completed, basin water managers are turning to the question of what happens next. That question, as we see it, is:

- Is there a chance at a “grand bargain” that addresses the unresolved questions head on?

- Or can the problems continue to be finessed, addressed at the margins, or put off into the future (the “incremental approach”)?

In preparation for this week’s Getches-Wilkinson Center summer conference at the University of Colorado, we have prepared a draft working paper sketching out some of the implications of the conclusions in our upcoming book on the relationship between the Colorado River’s hydrology and its management rules (Science Be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River).

The “what happens next” question is currently focused on 2026. That is how long the 2007 Interim Guidelines, DCPs, and Minute 323 last, and discussions are already underway about what sort of management regime will follow.

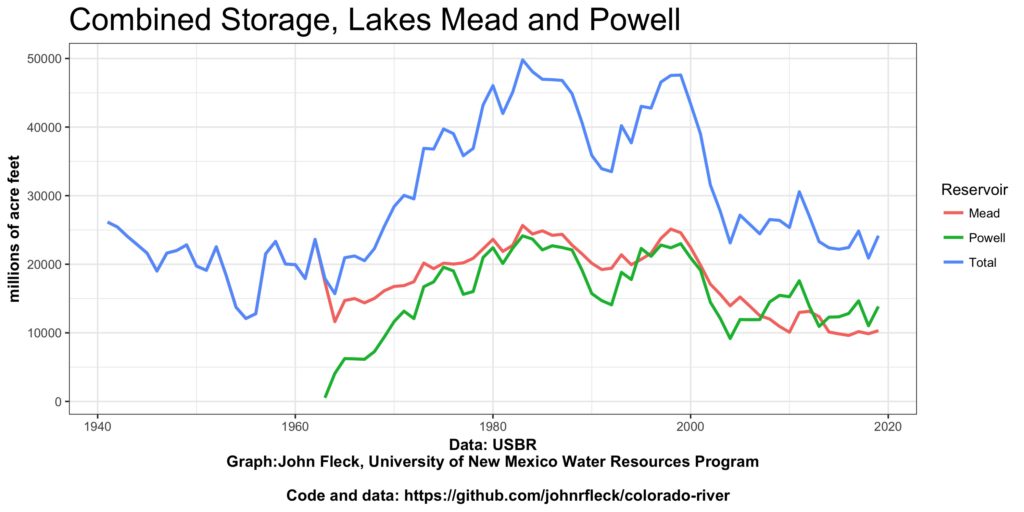

The DCPs go a long way toward reducing the imbalance between the river’s available supply and the allocation rules written over the previous century. But everyone knows they do not go far enough.

We suggest there are three salient, interconnected, unresolved Law of the River questions left by past failures to take the river’s hydrology seriously:

- Uncertainty over the Upper Basin’s legal obligation to Mexico under the Colorado River Compact

- Lower Basin overuse of its Compact allocation

- The lack of a definition of “extraordinary drought” in the U.S.-Mexico treaty

Each represents a serious issue left unresolved by the incrementalism of past Colorado River rule modifications. We believe that, taken together, they offer an opportunity for a “grand bargain” for the post-2026 Colorado River management regime.

What is the obligation of the Upper Basin to Mexico under Article III(c) of the Colorado River Compact?

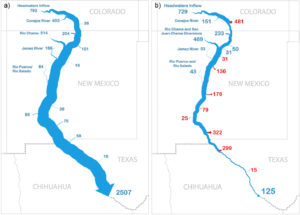

The mistaken presumption circa 1922 that there was a surplus of unallocated water in the Colorado River beyond the 16 million acre-feet of apportioned to the Upper and Lower Basins has left a lingering legal ambiguity about the Upper Basin’s obligation to contribute water at Lee Ferry to help meet the U.S. obligation to Mexico.

Under the several different possible interpretations of Article III(c) of the Colorado River Compact, the Upper Basin’s annual deliveries to meet its share of the U.S. obligation to Mexico could be as low as nothing to as high as 800,000 acre-feet per year. The dispute has never been addressed by the Supreme Court. Since the promulgation of first Long-Range Operating Criteria (LROC) in 1970, Glen Canyon Dam has been operated as if the Upper Basin’s obligation to Mexico is 750,000 acre-feet per year, a “minimum objective release” of 8.23 million acre-feet per year. Under the 2007 Interim Guidelines, annual releases are more flexible, varying from 7.48 to 9.0 MAF (7.0-9.5 in the bottom tier), but the 8.23 MAF release was intended to be the fulcrum. Over the life of the guidelines, the number of 7.48 MAF releases was designed to be about the same as the 9.0s. The States of the Upper Division have always objected to the 8.23 MAF release because they disagree with the interpretation of III(c) that requires a 750,000 acre-feet per year delivery to Mexico from the Upper Basin. But under the theory that they were not actually injured or impacted, they accepted it. Today, with the advent of demand management, that dynamic has changed. If for the post-2026 river guidelines the States of the Upper Division again accept the 8.23 MAF annual release and its implied interpretation of the Upper Basin’s Mexico obligation, and the hydrology the basin has experienced since the late 1980s continues or declines, the water supply available to the Upper Basin will be reduced and the cost of using water in the Upper Basin will be increased.

Will the Lower Basin continue to overuse its 8.5 million acre-feet apportionments under Article III(a) and (b) of the Colorado River Compact or will it implement a program to reduce its uses (including tributaries and reservoir evaporation) down to 8.5 MAF?

Based on the data available from the Bureau of Reclamation’s Consumptive Uses and Losses Reports, there is little question that, including tributary use and reservoir evaporation, the Lower Basin is using far more than its total 8.5 million acre-feet of apportionment under the 1922 compact. Based on the most recent data available, U.S. total Lower Basin use is at least 10 million acre-feet per year.* A compelling case can now be made that through the implementation of the Upper Basin DCP (with demand management) and Minute 323, Mexico and the Upper Basin are subsidizing this overuse. For the renegotiations, the Lower Basin has two basic approaches: It can continue to insist that the other two parties accept this overuse while its makes incremental progress toward reducing uses under a post-2026 version of their DCP (the incremental approach) or will it ask the Upper Basin and Mexico to accept some long-term level of overuse by offering them something of long-term major value (the Grand Bargain approach).

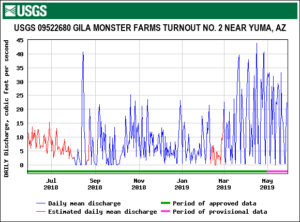

*To be conservative, we’ve assumed that Lower Basin main stem uses are ~7 million acre-feet per year -reflecting the recent conservation measures, ~1 million acre-feet per year of reservoir evaporation and system losses as water is delivered downstream from Lake Mead, and ~2 million acre-feet per year of tributary water use, reflecting the 2000-2004 period of extremely low water availability.

Can Mexico and the United States agree on a definition of “extraordinary drought” under Article 10 of the 1944 Treaty with Mexico?

The U.S.-Mexico treaty includes language that would reduce deliveries to Mexico under an “extraordinary drought”. But the phrase has never been defined.

Under Minutes 319 and 323, Mexico voluntarily agreed to take shortages, avoiding the treaty question. Statistically, the case that the basin is currently in an extraordinary drought is difficult. The 2005-2017 natural flow at Lee Ferry averaged 13.87 MAF/year, only slightly below the long-term 1931-2017 average of 13.98 million acre-feet per year. The “stress test” period of 1988-2016, 13.19 MAF/year, is slightly wetter than 1953-77, 12.89 MAF/year, (USBR NFDB March 2019). A second related policy question is that if climate change is slowly reducing the “normal” natural flow at Lee Ferry, how do we even know we’re in an extraordinary drought? The question is directly related to the Lower Basin’s overuse of its compact entitlement and the disputed question of the Upper Basin’s obligation to Mexico under Article III(c).

As the post-DCP negotiations proceed, will the U. S. basins first negotiate their own deal, then hope Mexico can be brought along as an afterthought? Or can the basin consider an integrated approach that addresses the Lower Basin’s overuse, the disputed Article III(c), and provides more certainty for deliveries to Mexico under the “extraordinary drought” provision?

What comes next

We believe there are several different reasonable outcomes for the post-2026 river:

Incrementalism I

The current package of the 2007 Interim Guidelines (with a few tweaks here and there), the Upper Basin and Lower Basin DCPs, and Minute 323 could be extended for anywhere from 5 to 20 years. The case for this approach is that it would maintain the recent momentum and give the basin more time to evaluate its effectiveness. Since this approach does not address the LB overuse and Article III(c) issues, it likely favors the Lower Basin at the expense of the Upper Basin and Mexico.

Incrementalism II

River operations could revert to the pre-2007 Long Range Operating Criteria-based operation (an 8.23 MAF minimum objective release plus occasional equalization releases) on a temporary or extended basis. This approach would not be a good outcome for the Lower Basin. The recent 9 million acre-feet per year releases have kept Lake Mead out of shortages. It’s not a great option for the Upper Basin because it continues the 8.23 MAF/year releases, but it may be a step that the Upper Basin should seriously consider if the Lower Basin is unwilling to address the overuse and Article III(c) issues.

The Downside of Incrementalism

The basin disputes, including but not limited to the Lower Basin’s overuse and Article III(c), could escalate to a point where one or more of the states decides to initiate interstate litigation. The conventional wisdom is that both basins would likely be losers in any actual Supreme Court litigation and the big winner could be the power of the secretary of the Interior. Several states, however, may view the threat of litigation as a useful negotiating tactic.

The Grand Bargain

The basin could take a broader approach to develop a more long-term sustainable solution that settles the disputed issues, a “Grand Bargain”. For discussion purposes, we’ve identified two sample grand bargain solutions, one based on a proposal made by Colorado in 2005 at a meeting in Albuquerque (Kevin Wheeler will presenting an analysis in his Boulder presentation) and a second one based on a simple compromise of the Article III(c) dispute.

We refer to our first sample as the Updated Albuquerque bargain. Under this suggestion the Upper Basin would agree to not object to the Lower Basin’s overuse and some form of an Upper Basin use cap. In return the Lower Basin would agree that the Upper Basin had no flow obligations at Lee Ferry (no threat of a compact “call”). Lakes Mead and Powell (and possibly other Upper Basin reservoirs) would be operated to maximize the yield and certainty of supplies for the Lower Basin and Mexico and address environmental issues. The three Lower Basin states and Mexico would share shortages in a manner similar to the current DCP and Minute 323.

Our second sample bargain is not as far reaching. We refer to it as the Article III(c) compromise. Under this this solution the basins would agree that the Upper Basin’s long-term obligation to Mexico is 375,000 acre-feet per year for a total ten-year Upper Basin delivery obligation of 78.75 million acre-feet and the new minimum objective release would be 7.785 million acre-feet per year. The Upper Basin would not challenge the Lower Basin overuse. Mexico would accept a proportional reduction in its normal year delivery of 50,000 acre-feet per year, a total of 1.45 million acre-feet per year. The extraordinary drought provision would be triggered whenever the Upper Basin can’t meet its ten-year obligation (78.75 MAF) without curtailing uses.

The Importance of Process

To be clear, we are not wedded to the specific details discussed in our examples of what a “Grand Bargain” might look like. As we explain in our forthcoming book Science be Dammed, “The process by which such a grand bargain might happen may be every bit as important as the technical details of what it would entail.”

The key here is to recognize that the problem the Colorado River Basin faces goes beyond a simple recognition that water is over-allocated, and uses need to be reduced. We must pursue that process in full recognition that the over-allocation became embedded in basin rules in very specific ways that remain unresolved today, and it is those specifics that must be fixed.

Further reading

For details, including more detailed historical and technical arguments underpinning the discussion above, see the latest draft of a work in progress, “The Upper Basin, Lower Basin, and Mexico: Coexisting on the Post-2026 Colorado River”, one of a series of working papers exploring the policy implications of Science be Dammed, available via SSRN. Links to this and other titles in the working paper series also will be posted on Inkstain’s Colorado River page.