By Eric Kuhn and Jack Schmidt

The press coverage of the December 2024 Colorado River Water Users Association (CRWUA) meeting mostly focused on the ongoing stalemate between representatives of the Upper and Lower Division States over their competing proposals for how the Colorado River Systems’ big reservoirs will be operated after the 2007 Interim Guidelines terminate in 2026. The headlines included words such as “turbulent”, “bitter”, “bluster”, and “spar”. Indeed, there was tension in the air, and the potential for interstate litigation was a topic of much discussion both on the formal agenda and in the hallways where, traditionally, progress is often made between competing interests.

While the press focus on the tension and divisiveness was unavoidable, I believe that there were good reasons for some guarded optimism.

For the ongoing effort to renegotiate the post-2026 operating guidelines, a consortium of seven environmental NGOs has also made a detailed proposal. Their proposal is referred to as the “Cooperative Conservation” proposal. One of the four action alternatives that Reclamation will analyze, Alternative #3, is patterned after the NGO submittal. At CRWUA, John Berggren of Western Resource Advocates, who along with Jennifer Pitt and others prepared the proposal, made a presentation on the proposal. Like the other submitted proposals, the cooperative conservation alternative proposes sophisticated operational rules for Lakes Mead and Powell based on combined system storage and actual hydrology. Where the Cooperative Conservation proposal breaks new ground is the concept of a Conservation Reserve Pool, and this idea could lead the basin toward a practical on-the-ground solution. Indeed, the Gila River Indian Community introduced at CRWUA a similar concept in the form of a Federal Protection Pool made up of stored water in both Lake Powell and Lake Mead. These proposals, taken separately, together, or in some combined and moderated form, might serve as a catalyst for compromise.

As proposed, both the Conservation Reserve Pool and the Federal Protection Pool would be filled with water conserved by reductions in consumptive use and perhaps augmentation from programs in both basins and this water could be stored anywhere in the system. This water would be “operationally neutral” and thus invisible to the underlying system management operating rules. From an accounting perspective, this Pool would “float” above other water in the reservoirs. Floating Pools operate separately from and above the prior appropriation system of water allocation on the Lower River and are invisible to the rules that dictate annual releases from Glen Canyon Dam. Thus, these proposals impart important operational flexibility. In many ways, Floating Pools split the baby—they incentivize innovative conservation measures that allow participants to find value they would not have been able to realize under the prior appropriation system—yet they insulate the prior appropriation system and thus are more protective of higher-priority water users than operationally non-neutral ICS. It’s a stretch to say there is something here for everyone, but there may be enough to kick-start otherwise stalled conversations.

In their proposal, the Lower Division States have offered to take up to 1.5 maf/year of mainstem shortages. Where the two basins remain deadlocked is what happens in those years when shortages exceed the amount the Lower Division States are willing to accept. The Lower Division States have proposed that the two basins share the additional required shortages up to a maximum shortage of 3.9 maf/year. The Upper Division States have said, “No, because we already suffer large hydrologic shortages in dry years, and we have not used our full compact entitlement; the Lower Division should cover all of the shortages.” In their presentation, however, the Upper Division Commissioners (UCRC members) left the door open for continuing discussions between the two divisions. In his remarks, New Mexico Commissioner Estevan Lopez stated that under what he referred to as “parallel activities”, the Upper Division States might be willing to discuss conserving “100,000, maybe 200,000 acre-feet per year.”

Water in Floating Pools could be used for a variety of purposes including environmental management, fostering binational programs, and supplementing scheduled water deliveries. During his CRWUA presentation, John Berggren mentioned an obvious use for this pool. Water stored in the Pool by conserved consumptive use programs in the Upper Division States could be used as an Upper Division contribution during years when mainstem shortages to the Lower Division States exceed a negotiated amount. Of course, the Lower Basin is unlikely to accept Upper Basin creation of Floating Pools made up of water for which there is no current consumptive use. This water is already “system water” and is now being used by existing Lower Basin water agency. Thus, it would be necessary to develop a program to account for and certify savings in the Upper Basin. Further, the thorny problem of shepherding (legally protecting the conserved water so that it ends up in system storage) needs to be overcome. For a perspective on this issue, see Heather Sacket. Undeveloped Tribal water is a controversial sticking-point in this regard, with strong feelings and strong arguments on all sides.

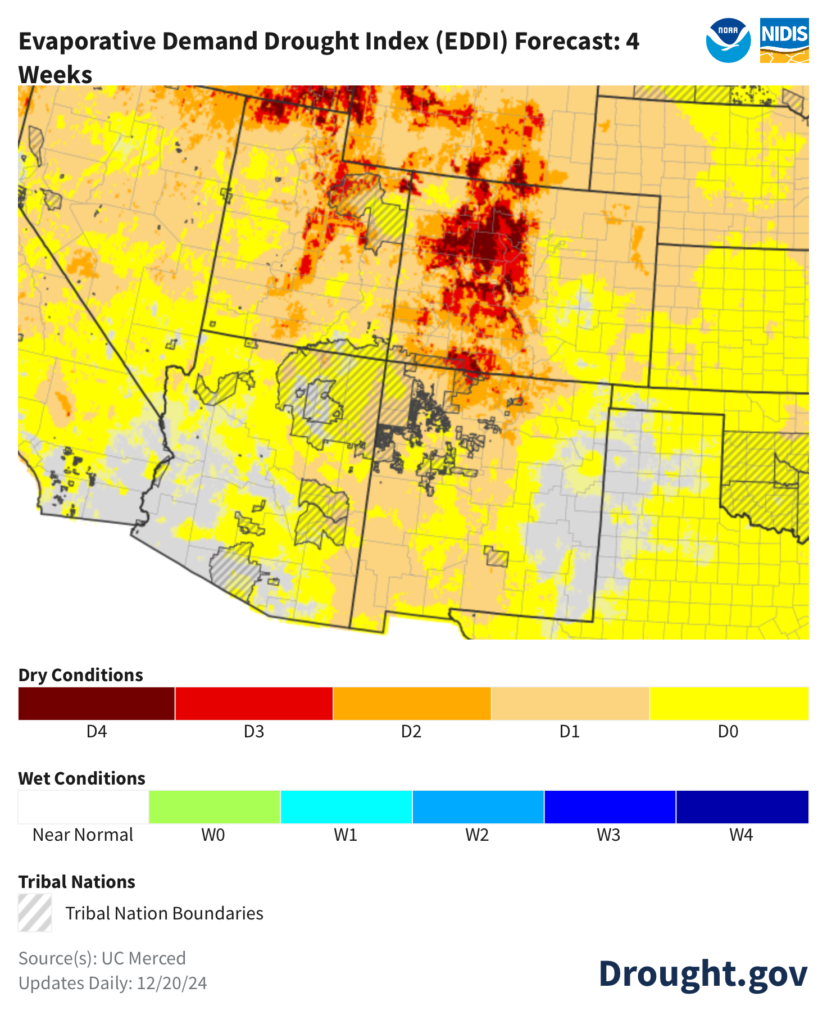

If the Upper Division States were to conserve 200,000 acre-feet per year for five years and deposit that saved water in a conservation reserve “Floating Pool”, something like 900,000 acre-feet could be available for shortage sharing (after accounting for reservoir evaporation). (We use 900,000 af as an example only, how much water the Upper Division States would have to contribute and maintain in a Floating Pool would have to be negotiated between the two divisions.) In their presentation, the Lower Division principals pointed out that had their proposal been in place beginning in 2007, there has yet to be a year when shortage sharing would have been required. Note, this conclusion is very sensitive to “initial conditions.” In 2007, total storage in Lake Mead and Lake Powell was about 8 maf more than it is today. If the 21st century hydrology continues, shortages greater than 1.5 maf/year are likely to occur.

What would the Upper Division States get in return? During the term of the new post-2026 operating guidelines (which we all assume will also be “interim”), the Upper Division would benefit by the Lower Division agreeing to remove the threat of litigation over a “compact call.” For a perspective on the potential impacts of a “call” in Colorado see The Risks and Potential Impacts of a Colorado River Compact Curtailment on Colorado River In-Basin and Transmountain Water Rights Within Colorado.

Carefully crafted with appropriate guardrails, Floating Pool concepts can be a catalyst for compromise between the two divisions that give both parties something they need.

How do Floating Pool alternatives fit with the Schmidt, Kuhn, Fleck management approach? Based on our conversations with the authors of the cooperative conservation proposal, we believe the two approaches agree — that our management proposal fits on top of and complements their proposal quite well. In my presentation at CRWUA, I emphasized that, like future hydrology, there is great uncertainty in the future needs of the river’s ecosystem and society’s values. It’s almost a certainty that in the future, prescribed annual releases from Glen Canyon Dam will cause an unacceptable and unanticipated outcome to some river or reservoir resource. When that happens, our flexible management approach and accounting system keeps the basins “whole.”

Is using the concept of Floating Pools as a catalyst to break the stalemate between the two basins without warts? – of course not. There are important considerations regarding the use of undeveloped water—Tribal or otherwise, and the devil is in the details when it comes to developing appropriate guardrails for annual and total accumulation in such a Pool, the number and type of participants, annual debits, and other important qualifications. Even conserving 100,000 acre-feet per year in the Upper Division States, with acceptable verification, could be a stretch, especially if there is less federal money in the future, as there almost certainly will be. Finally, it might put off addressing fundamental problems with the law of the river until the new post-2026 operating rules again expire. When they do, the 1922 Compact and 1944 Treaty with Mexico will still be in place, and these agreements collectively allocate 17.5 maf/year of consumptive use on a river that is only producing 13-13.5 maf/year of water at the international boundary (and runoff continues to decline). What the Floating Pool concept might accomplish is to significantly reduce the temptation and threat of unpredictable interstate litigation, keep the basin’s stakeholders talking to each other, and give us time to move toward more foundational change in how the river is managed.