Managing outdoor water use while maintaining urban tree cover is a key challenge for water managers in arid climates. Urban trees generate flows of ecosystem services in arid areas, but also require significant amounts of irrigation. In this paper, a bioeconomic-health model of trees and water use is developed to investigate management of an urban forest canopy when irrigation is costly, water has economic value, and trees provide ecosystem services. The optimal tree irrigation decision is illustrated for Albuquerque, New Mexico, an arid Southwest US city. Using a range of monetary values for water, we find that the tree irrigation decision is sensitive to the value selected. Urban deforestation is optimal when the value of water is sufficiently high, or alternatively starts low, but grows to cross a specific threshold. If, however, the value of water is sufficiently low or if the value of tree cover rises over time, then deforestation is not optimal. The threshold value of water where the switch is made between zero and partial deforestation is well within previously identified ranges on actual water values. This model can be applied generally to study the tradeoffs between urban trees and water use in arid environments.

Gila River Indian Community balks at Arizona’s latest scheme for Colorado River cutback

A new letter from Gila River Indian Community Gov. Stephen Lewis to Arizona’s two top Colorado River negotiators complains that the latest version of the state’s plan to reduce its use of Lake Mead water would make things worse, in way that actual gives some Central Arizona farmers more water than they would get under the current Colorado River operating rules.

As a result, GRIC negotiators have been instructed to reject the latest proposal.

The latest incarnation of the Arizona Plan, Lewis charges, violates “the rules of holes”.

This is another big setback to hopes to wrap up a Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan soon.

(View the full text of the letter here.)

Colorado’s east-west water divide poses risks for completion of a Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan

tl;dr: A feud over how to implement Colorado River conservation adds another hurdle to final completion of the Colorado River Drought Conservation Plan.

longer: While Colorado River Basin folks have been paying obsessive attention to Arizona’s struggle to come up with an internal agreement to cut back on its use of Colorado River, a second within-state argument, less noticed, has emerged into public in the state of Colorado that also poses risk for getting the Colorado River’s Drought Contingency Plan signed by the end of the year.

At issue is the path Colorado takes to reducing its use of water in the event of an Upper Colorado River Basin shortage. For years, the mantra has been “voluntary, temporary, and compensated.” If there is a shortage, the mantra suggests, some water users – most likely farmers, and the most likely farmers are on Colorado’s west slope – would be paid to temporarily curtail their uses.

confluence of the Colorado River, left, and the Roaring Fork, in Glenwood Springs, Colorado. Note coal train for scale.

The water would go into a new storage pool being created by the DCP, water set aside to meet the Upper Basin’s delivery obligations under the Colorado River Compact, a sort of watery savings account. It would be used, in times of bad hydrology, to make sure the Upper Basin can meet its Lee Ferry delivery obligation under the Colorado River Compact. The question of how to fill the account ahead of time, before the risk becomes too great, has been difficult. “Voluntary, temporary, and compensated” has been a guiding principle. No farmer could be forced to contribute.

But in the last month, an alternative idea that had been discussed behind the scenes has been creeping into public view – the question of whether “voluntary, temporary, and compensated” would be enough. It first appeared in a memo last month from the staff of the Colorado Water Conservation Board, the state’s primary water policy agency. One of the key questions, the memo noted, was “whether the program would be limited to temporary, voluntary, and compensated conservation activities or be expanded to include something more”.

In a report last week to the Colorado River Water Conservation District Board*, river district director Andy Mueller was blunt in describing the ensuing discussions at the CWCB meeting during which the issue was discussed:

The Front Range representatives affirmed their position … that a voluntary program was a fine goal but that they believed the state needed to roll out a program which includes rules and requirements for mandatory anticipatory curtailment. The presentation from the string of Front Range entities confirmed the River District Staff’s concerns that major water users in the state would like the Upper Basin Demand Management pool established quickly with the intent that it be filled with water from a program highly or exclusively dependent upon water contributed via uncompensated, anticipatory, mandatory curtailment of water rights in the Colorado River Basin.

This is a manifestation of Colorado’s historic east-west water divide, a source of political tension that goes back nearly a century. Growing cities in the urbanizing east covet water. The rural west has water. This tension makes solving the problem of how to fill the compact compliance pool contemplated by the DCP tough. And you should add it to your list of outstanding problems that could derail the seven state interstate agreement.

Here’s the dilemma. In addition to a package of interstate agreements, DCP seems to require federal legislation. And if you look at the documents released Oct. 10, you’ll see that one key piece of the puzzle is that the Upper Basin is insisting as part of the package on legislative authorization to create the drought storage savings account. This gives Mueller and the River District (the central governance entity looking out for West Slope water interests) the leverage to demand that “voluntary, temporary, and compensated” be built into the idea of drought storage from the beginning. From Mueller’s memo to his board (“UCRC” here is the Upper Colorado River Commission, which represents the four Upper Basin states; “FRWC” is the Front Range Water Council, representing east side, largely but not entirely municipal water agencies):

We believe that if a Demand Management pool is created through federal legislation and action by the UCRC (starting with the execution of the currently contemplated DCP documents), that there will be a significant push by the members of the FRWC to move immediately to an anticipatory, non-compensated curtailment model of contribution to the pool. We respectfully, but strongly disagree with the concept that the push for federal legislation and the execution of the Upper Basin DCP documents are not inherently tied to the establishment of a demand management program within the state of Colorado. If the pool is established without a commitment to principles designed to protect Western Colorado agriculture and initially limited to the publicly vetted concept of a voluntary compensated program, Western Slope agriculture is at risk of quickly becoming the sacrifice zone.(emphasis added)

Brent Gardner Smith has been doing a nice job of covering this for Aspen Journalism:

“This just shows how important it is to get the demand-management program right, and that we don’t rush into a demand-management pool in Lake Powell before we’ve had this discussion and before we’ve agreed to a policy and principles to guide us,” said Tom Alvey, the current president of the district’s board, who represents Delta County. “From all the perspective of water users on the Western Slope, there is huge concern about this.”

And therein lies the dilemma for the seven-state DCP. It is generally accepted that federal legislation only happens if all seven states (and therefore their 14 U.S. senators) agree. If they do, we could see something after the election, in the lame duck session of Congress. But Alvey and his River District colleagues may have blocking power. If Colorado’s water users aren’t on the same page on this, there is a risk that Colorado’s senators may not go along with a DCP bill.

The CWCB’s Brent Newman tried to reassure the River District Board at last week’s meeting. Per Brent Gardner Smith’s story:

Newman … emphatically told the river district’s directors Tuesday that the state is not working on a mandatory curtailment program to avoid a call on the river system under the 1922 Colorado River Compact.

“Not myself, not the CWCB staff, not our board, not the Attorney General’s Office, not the division of water resources, not the state engineer, none of us at the state are assessing or recommending any kind of mandatory anticipatory curtailment scenario,” Newman said. “That is not in our books. Yes, we’ve had some water users say that if voluntary, temporary and compensated isn’t sufficient, you may have to look at this. We are not doing that.”

So I guess add Colorado’s name below Arizona’s on your list of “places where stuff needs to be worked out before the DCP can happen.”

* Disclosure: I have worked in the past as a consultant to the River District on a study of the risks of drought and climate change to Colorado River supplies, specifically intended to answer questions about how much water might be needed to fill the kind of savings account described above. I am also currently collaborating on a book with former River District General Manager Eric Kuhn.

The draining of New Mexico’s reservoirs continues

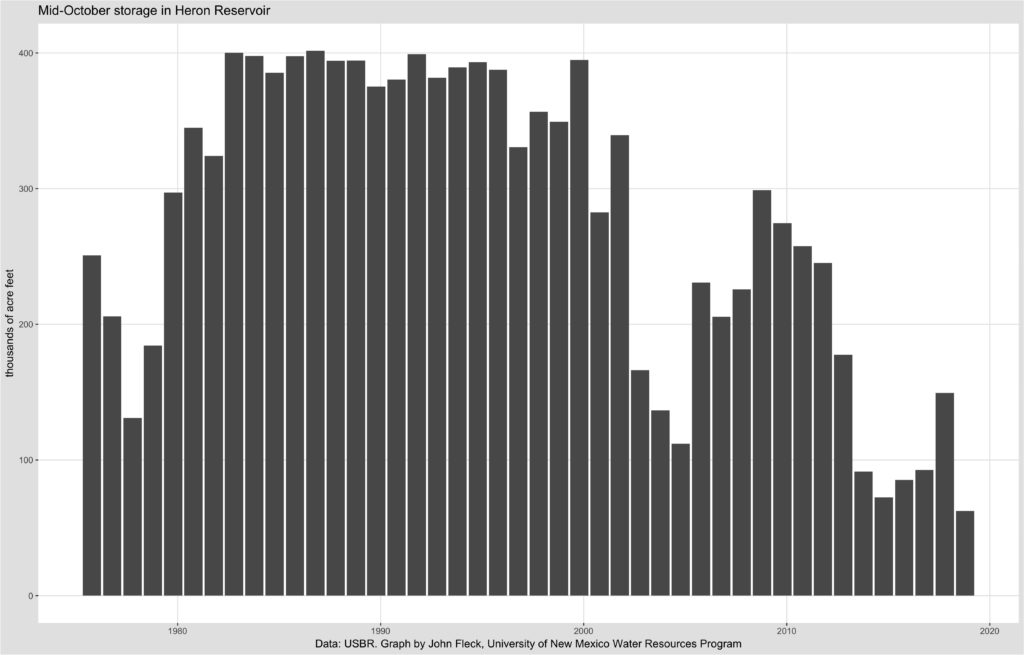

Heron Reservoir, the first stop for central New Mexico’s imported Colorado River Basin water, dropped Oct. 10 to its lowest level since filling after it was first built in the 1970s:

As I noted last month, total storage on New Mexico’s part of the Rio Grande system is at historic lows. I updated the numbers this morning, that hasn’t changed.

Here’s the obligatory picture of the Rio Grande through Albuquerque from yesterday’s bike ride. Looks pretty much like every other picture I’ve taken there this morning, though you can tell I’m not cheating by the bits of yellow beginning to decorate the cottonwoods.

Creating a conservation storage pool in Lake Powell

It’s apparently Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan week! Documents here. This is when we all gather around and try to make sense of the sweeping effort to ratchet up efforts to reduce Colorado River water use to keep the system from crashing.

The plan you see before you is really not that different, at the interstate level, from what was essentially agreed to nearly three years ago – Arizona and Nevada agree to bigger reduction in their Colorado River supplies earlier, based on the elevation of Lake Mead. If Mead drops far enough, California joins the party, where by “party” I mean “sees its Colorado River supplies cut as well”. So this is one of those parties you really don’t want to go to, because you’re super introverted, but….

The most interesting bit now seems to be the halting progress toward a new set of rules that allows the states of the Upper Colorado River Basin – Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico – to create a conservation storage pool in Lake Powell. One of the sticking points in planning for water reductions up here (in the Upper Basin) is that if we conserve water and prop up Lake Powell in the process, under the current rules, we risk simply increasing the release to Lake Mead. We risk losing a chunk of the water we conserve.

The idea under DCP would be to create a separate accounting category in Powell for conserved water that’s “invisible” (the word people have been using) to the Powell->Mead water sharing rules. The details here are hairy, in terms of ensuring that conservation is really happening and accounting for it in a way that’s transparent and agreeable to the states of the Lower Basin.

But the fact that we seem to be getting something of this sort, or at least an agreement on the general outline of how it might work, is a big deal.

Mill Creek

Mill Creek is a bit of a cipher as it slips through Walla Walla.

Flowing out of the Blue Mountains, it is the southeast Washington town’s primary water supply, and its geographic organizing principle. But the “creek” itself, as it flows through the town built on its banks, is confined to a concrete channel, in some parts of town an ignored back alley sort of thing, elsewhere roofed over completely by the buildings of downtown.

When I came here in the fall of 1977 to attend Whitman College, my friends and I immediately found it, though, out the back door of Anderson Hall where we all were scared and excited youngsters in equal parts eager and terrified by this new step in our lives. We’d hop down the wall and walk downstream late at night, slipping beneath downtown in the darkness and out toward the fields on the west end of town.

I’ve written since about how, whenever I go to a new place, I end up going down to its water – a bay, a beach, a river, a concrete creek. At risk of a post hoc reconstruction of the meanings of my life, it occurred to me as I returned this week to Walla Walla for the first time in years that Mill Creek must be the place where this started.

I was staying at the Marcus Whitman downtown – just offices and residential apartments when I lived here four decades ago, now an upscale hotel catering to wine tourists. When Lyman Persico, a Whitman College geology professor and my host for a few days’ visit to my alma mater, dropped me off Sunday afternoon, I dumped my bags and headed for Mill Creek.

One of my great joys has always been walking around, aimlessly, and it occurred to me that Sunday afternoon as I retraced the steps 18 and 19 and 20 and 21-year-old me walked so very many times that this joy is rooted here. It was a happy place, and I thoroughly enjoyed visiting with 20-year-old me. I’m not that person any more, but I liked meeting him again after all these years.

During some of the down time between my visits to Lyman’s environmental studies classes, I rented a bike to increase my range, visiting all the places I lived – two dorms, a lovely apartment building up Boyer Avenue, and a shitty old rental house on Rose Street that has not worn the subsequent 40 years as well as I have.

I felt lost sometimes, my mental map ripped with holes, some because of a changed landscape, much because of my own hazy memories.

I turned to my cell phone to find my way to the Washington State Penitentiary, on a hill west of town. It was a gut check moment as I wheeled onto the state highway that leads to the pen and saw the big water tower.

I was, I think, just twenty when I first visited the place.

I was, I think, just twenty when I first visited the place.

I’d been working weekend shifts at a local commercial radio station, “adult contemporary” soft pop. It was a small operation, but made a pretense of covering the local news. There had been a riot at the penitentiary, and I got a call from the station asking if I could go cover the warden’s news conference.

It was a big deal. The networks had crews there. It was national news.

I was a long-haired punk (in the Ramones sense of that word), and the thing I remember most is when a guard stopped me, leaving after the news conference, to make sure I wasn’t escaping. I couldn’t have understood the importance then, but it was my first act of paid journalism.

A couple of years later, I ended up as “news director” at the same radio station, barely more than minimum wage, but it was an act of becoming – becoming a real, paid journalist. And I covered the state pen.

Thus, here, it all began.

Come help solve the Rio Grande’s problems: the NM Interstate Stream Commission is hiring

A great job here, helping solve problems on the Rio Grande:

The incumbent will be responsible for independent technical and scientific engineering decisions based on the principles and methods of hydrologic/water resources analyses and evaluation. The position will required advanced technical analyses of complex hydrologic and water resource engineering issues; an in depth understanding of the history and administration of the Rio Grande Compact and the Bureau of Reclamation’s Rio Grande project. The incumbent will be responsible for managing professional service contracts in the ares of hydrogeoloygy, water quality, water use, water resources investigations, and river and reservoir operations. The position will also develop annual funding requests, and, at the request of the Legal Manager, coordinate on work plans/projects to gain a better understanding of Rio Grande Basin hydrogeology and apply those findings to determine informed, defensible, water management decisions. The position may also manage projects and professional service contracts related to river management and Endangered Species concerns in the middle Rio Grande.

The drying of New Mexico’s Rio Grande

I went on a bike ride this morning to get a look at the Rio Grande through Albuquerque. Flows dropped below 100 cubic feet per second Thursday evening for just the second time since we moved here in 1990. Flows this low are hard to measure – we didn’t get a numerical picture of just how bad things are until the USGS river measurement people calibrated their Central Avenue gauge Friday morning.

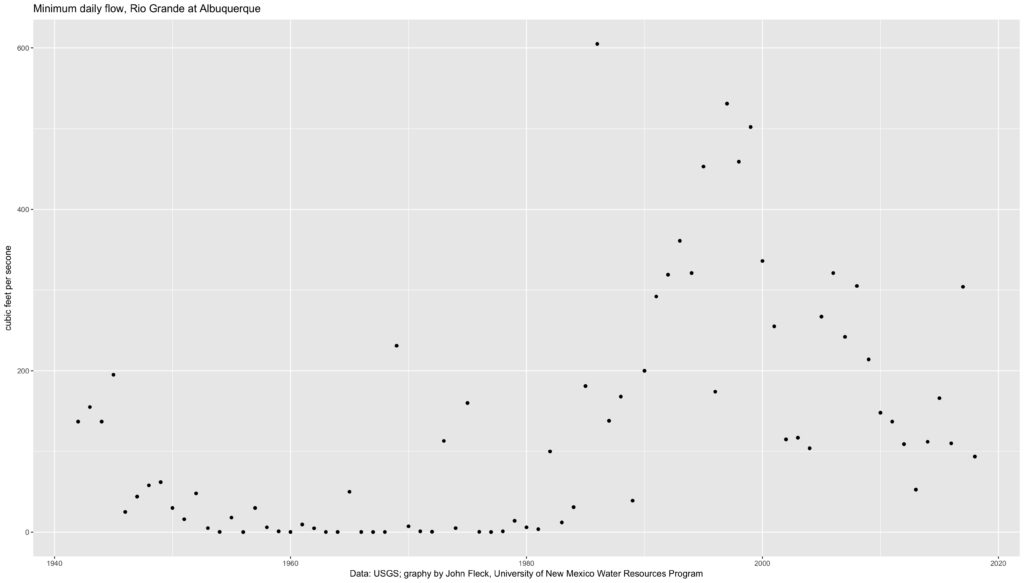

The other time we had flows this low during my tenure as an Albuquerque resident was September 2013 (I remember it well, I was covering the heck out of the river for the Albuquerque Journal at the time). But it’s worth looking back in time, because the flows we’re seeing this year, which are freaking me out, used to be a nearly annual affair. Here’s a plot of annual minimum flow, based on USGS data:

This is a classic result of what I’ve come to call “an institutional hydrograph”. A hydrograph is a graph of flow on a river over time. In its normal form, it responds to seasons, weather, and climate. But in its institutional form, it responds to rules and policies and norms of human behavior in managing the river.

Those zero-flow points on the left half of the graph are institutional. From the mid-1940s to the early 1980s, we dried the river through Albuquerque almost every year. I phrased it that way on purpose – not “the river went dry” but “we dried the river”. If you look at upstream gauges, there was water in the Rio Grande, flowing into the central valley where Albuquerque sits. But the irrigation agency that provides water to this valley’s farmers diverted it all, running its ditches full, so that by the time the Rio Grande reached Albuquerque, it was dry.

I’m hazy on some of the history, but by the time I started paying attention to the Rio Grande in the 1990s, a combination of community environmental values and the strictures of the Endangered Species Act had triggered changes in irrigation management. As a matter of policy we now leave water in the river. So for my generation of river-watchers, this is a really striking thing to see:

Tough to be a fish in the Colorado River

As Lake Powell drops, a waterfall forms at the reservoir’s upper end as the San Juan cuts down through sediments dropped when the reservoir was fuller. The resulting waterfall is a bit of an obstacle to fish:

The razorback sucker population estimate for 2017 alone was 755 individuals and, relative to recent population estimates ranging from ~2,000 to ~4,000 individuals, suggests that a substantial population exists seasonally downstream of this barrier. Barriers to fish movement in rivers above reservoirs are not unique; thus, the formation of this waterfall exemplifies how water development and hydrology can interact to cause unforeseen changes to a riverscape

Draining the reservoirs on New Mexico’s Rio Grande

tl;dr

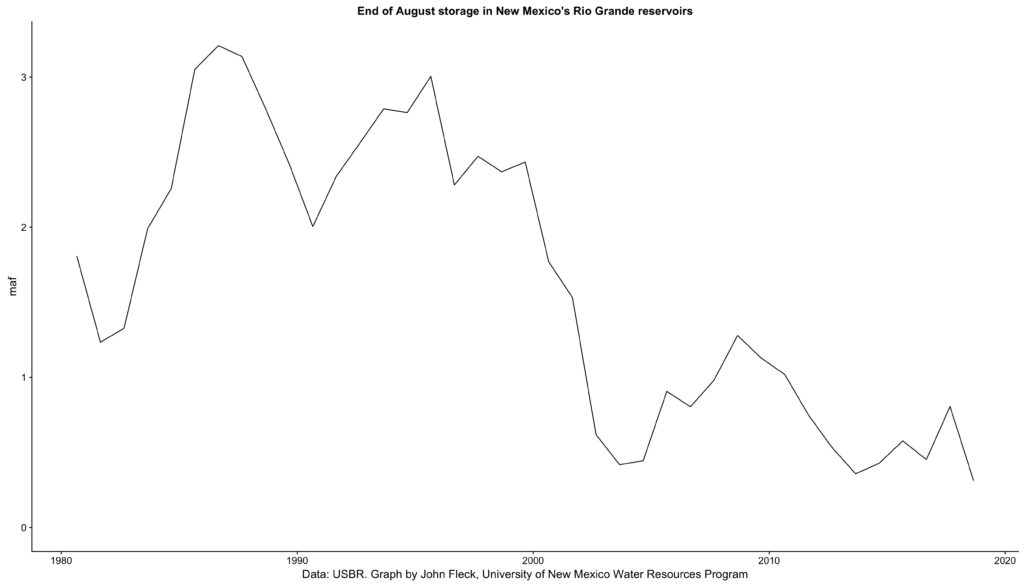

Total reservoir storage on the Rio Grande in New Mexico at the end of August was the lowest it’s been since at least 1980.

longer (with graphs!)

In our University of New Mexico Water Resources Program class, we’ve been discussing the state of the Rio Grande in real time. This feels like a remarkable moment, for teaching.

The water managers down on New Mexico’s Lower Rio Grande have made the conscious decision to essentially drain Elephant Butte Reservoir – the primary source of surface water supplies for farmers in the Hatch and Mesilla valleys. Elephant Butte, a 2 million acre foot reservoir, ended August with just 85,000 acre feet of water, something like 4 percent of capacity. That’s the lowest it’s been at this point in the year since 1972.

Simultaneously, we’ve made a similar decision upstream – draining Abiquiu, El Vado, and Heron reservoirs on the Rio Chama in order to continue deliveries to farmers in this part of the state, with some water devoted to instream flows for the endangered Rio Grande silvery minnow.

We essentially manage the two parts of the system separately, but I was wondering what it would look like if we looked at them together:

The US Bureau of Reclamation datasets available on a Sunday afternoon lack the necessary detail prior to 1980 for some of the reservoirs, so that’s as far back as the graph goes.

We’re draining these things and hoping for a wet winter.