Crashing Lake Mead

Sunday afternoon, I crashed Lake Mead.

This was not difficult.

Each spring, UNM Water Resources Program students do a case study of a river basin as they’re learning dynamic simulation modeling, linking hydrology, economics, and rules. This year, we’re doing the Lower Colorado River Basin.

In the WRP curriculum, we’re big on understanding the rules by which we manage water as a resource – where they come from, and how they work.

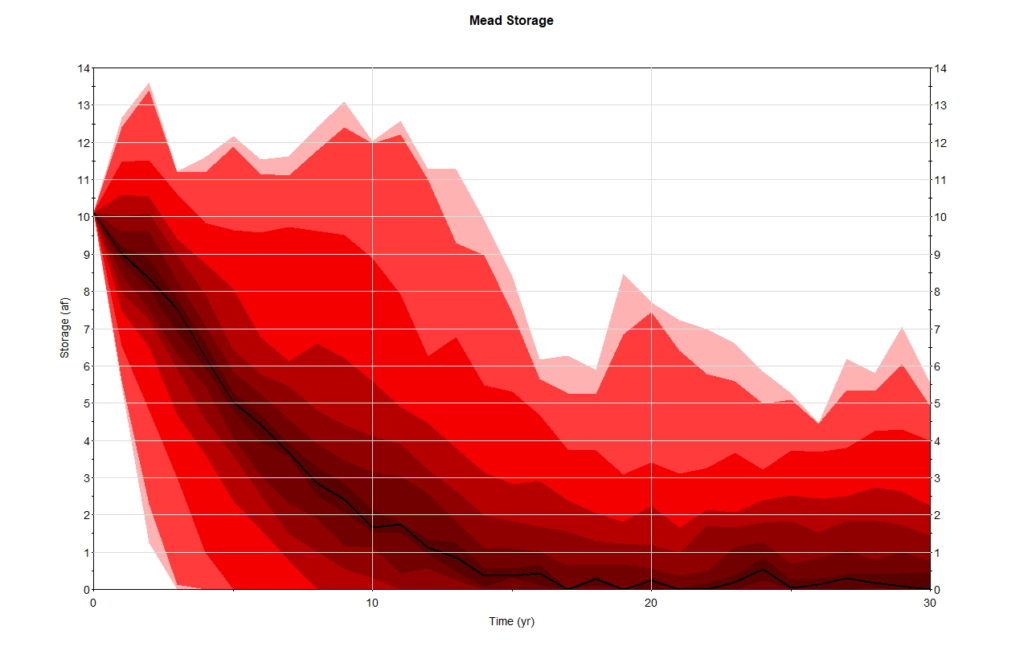

The model results above are a perfect example of George Box’s famous dictum that “all models are wrong but some are useful.” The Goldsim model, which I wrote really fast because I needed something for tomorrow’s lecture, is a super-simple simulation of the water allocation hydrology and rules in the classic Bureau of Reclamation “structural deficit” slide, combined with a Monte Carlo simulation of some reasonable assumptions by me about 21st century inflow hydrology from the Upper Colorado River Basin.

Within a decade in my model, Lake Mead is kinda unusable, doing little more than passing through whatever water comes down from upstream. Under some scenarios, my simulation quickly throws an error, informing me that you can’t have negative water in a reservoir.

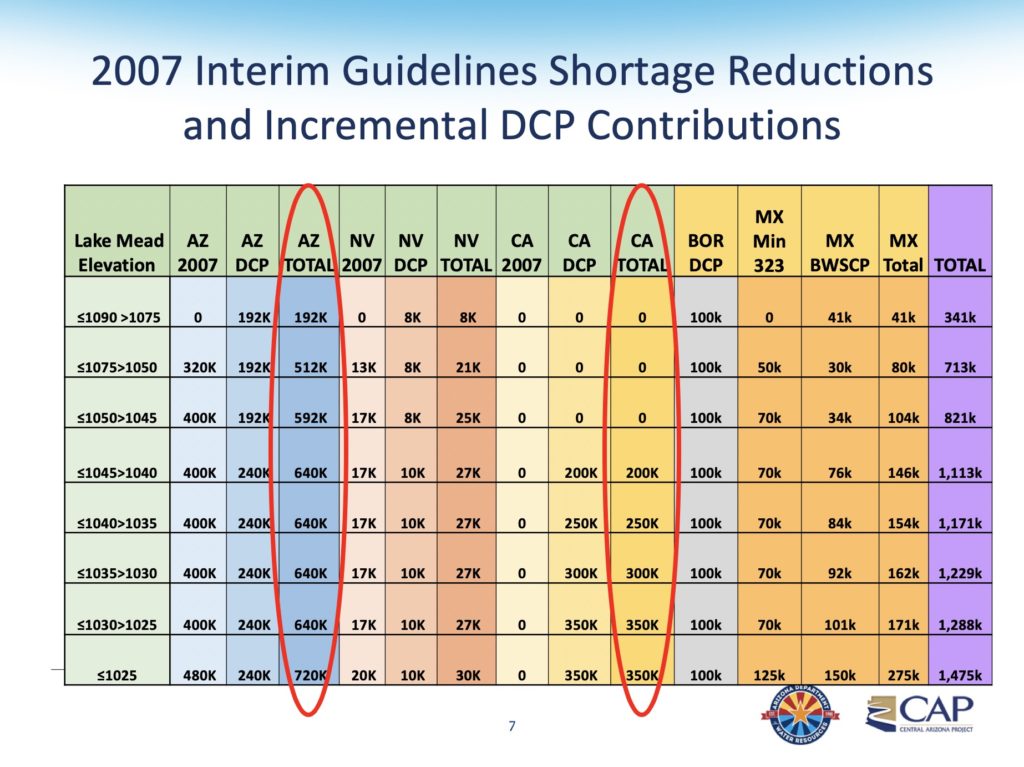

The rules here, which govern now much water gets released from the reservoir, are encoded in the Colorado River Compact and the Boulder Canyon Project Act, as interpreted by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1963 Arizona v. California decision.

Obviously this is the “all models are wrong” part of Box’s dictum. This is a realistic view of the system if we don’t do anything. It’s not a realistic view of the system because it assumes people won’t say “OMG Lake Mead is almost empty we’ve gotta do something!” Which is what they’re now saying, which is why new and better rules are being written.

This spring’s assignment to our water resources students is to experiment with ideas about what those new rules might look like, how they might work.

I’m very much looking forward to this. I think it will be useful.

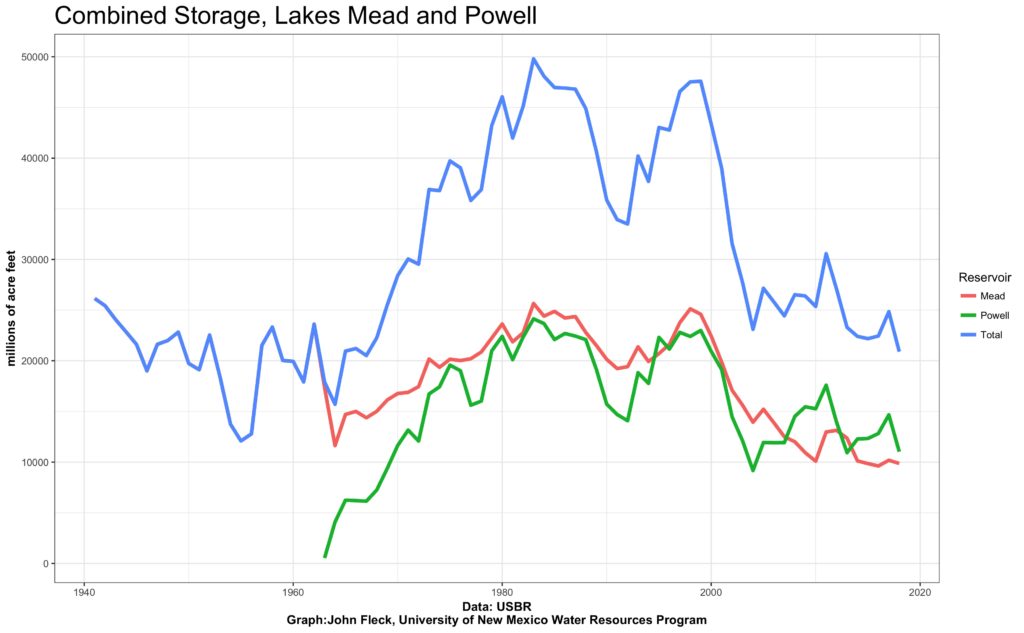

By the numbers, Lake Mead began 2019 at elevation 1,081.47 feet above sea level, down a foot in 2018. This comes in spite of yet another Upper Basin release of 9 million acre feet from Glen Canyon Dam last year, an extra 770,000 acre feet above the 8.23 million acre feet the Lower Basin can rightly expect under the Law of the River. Since 2000, the Upper Basin has delivered an excess of 9.8 million acre feet from Glen Canyon Dam above and beyond the 8.23 million acre feet expected every year under the current interpretation of the Law of the River. In that time, the level of Lake Mead has declined 115 feet.

By the numbers, Lake Mead began 2019 at elevation 1,081.47 feet above sea level, down a foot in 2018. This comes in spite of yet another Upper Basin release of 9 million acre feet from Glen Canyon Dam last year, an extra 770,000 acre feet above the 8.23 million acre feet the Lower Basin can rightly expect under the Law of the River. Since 2000, the Upper Basin has delivered an excess of 9.8 million acre feet from Glen Canyon Dam above and beyond the 8.23 million acre feet expected every year under the current interpretation of the Law of the River. In that time, the level of Lake Mead has declined 115 feet.