The Boulder Canyon Project Act, carved in stone

Touring Hoover Dam Friday afternoon, a friend deeply embedded in the “Law of the River” asked if I knew that Section One of the 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act was carved in stone on one of the Dam’s iconic towers:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That for the purpose of controlling the floods, improving navigation and regulating the flow of the Colorado River, providing for storage and for the delivery of the stored waters thereof for reclamation of public lands and other beneficial uses exclusively within the United States, and for the generation of electrical energy as a means of making the project herein authorized a self-supporting and financially solvent undertaking, the Secretary of the Interior, subject to the terms of the Colorado River compact hereinafter mentioned, is hereby authorized to construct, operate, and maintain a dam and incidental works in the main stream of the Colorado River at Black Canyon or Boulder Canyon…. (emphasis added)

The carving (or maybe it’s cast concrete? further research needed) sits atop the Nevada side elevator tower, and as we were finishing our tour, we lingered on top of the dam, thinking about the implications.

I apologize for the picture. The light wasn’t great. I tried going back early Saturday morning, hoping sunrise light would highlight it better, but alas I think I need to return in spring or summer, when the rising sun might cast the shadows that would better highlight this institution carved in stone. (I do not view a need to return to Hoover Dam as a problem.)

I’ve got a couple of working titles for the next book on which I’m starting to work. “The Ghost of Water” has been my go-to in the last few months as I begin to sketch out the ideas, but as I toured the dam with old Colorado River friends Friday I added one to the mix: “Hoover Down“.

The idea is that we create institutions, and then those institutions shape the land. In between institutions and land sits Hoover Dam.

By “institutions” here I mean not government agencies, but the more expansive definition we teach University of New Mexico Water Resource Program students:

Institutions – the rules of the game, both formal and informal, that both liberate and constrain behaviors in repeated interactions

It’s wonky language, and it took me a while to get my head around the distinction between this expansive definition and the more traditional “institution = government agency” idea. At Hoover Dam, the institution in question is in significant part the Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928. (The more traditional idea of what people mean when they talk about institutions, the Bureau of Reclamation, is in this case the tool we use to carry out the rules written down by Congress in 1928.)

In retrospect, there’s a thread in the three books I’ve written that leads in this direction:

- The Tree Rings’ Tale, written for kids, was mostly, “Hey, science about water, how cool is that?”

- Water is For Fighting Over tackled the interplay between the “formal” and “informal” parts of the definition of institutions, and the operation of “the network”. It’s my attempt to make sense of the institutions.

- Science Be Dammed, thanks to the remarkable insights of my co-author Eric Kuhn, brought the science and the institutions together in a way I think frankly has never been done for the Colorado River.

Hoover Down

During our tour Friday, the kind folks at the Bureau of Reclamation took a group of us down on the power plant floor, where in our post-9/11 world tourist tours no longer go. Standing amid the massive generators on the Arizona side, it was weirdly quiet. There was very little water flowing through Hoover Dam. Why?

friends with the keys gave us a tour of the place

Part of the reason is the changing nature of the power grid. Hydroelectric power plays an increasing role in filling in behind renewable resources when they go off line, so Hoover’s generators tend to ramp up when the sun sets in California.

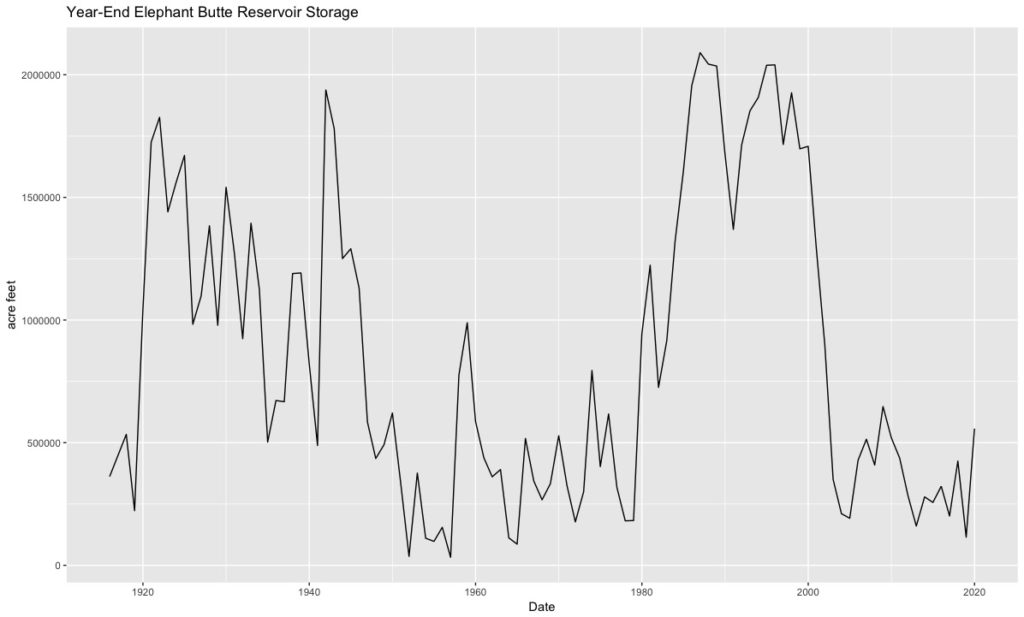

But part of the reason involves the shifting nature of water management uses and rules downstream. There is simply less water moving through the dam than there used to be. The complex tangle of rules – institutions – is successfully encouraging folks downstream to bank their water in Lake Mead rather than taking it out and spreading it across the land.

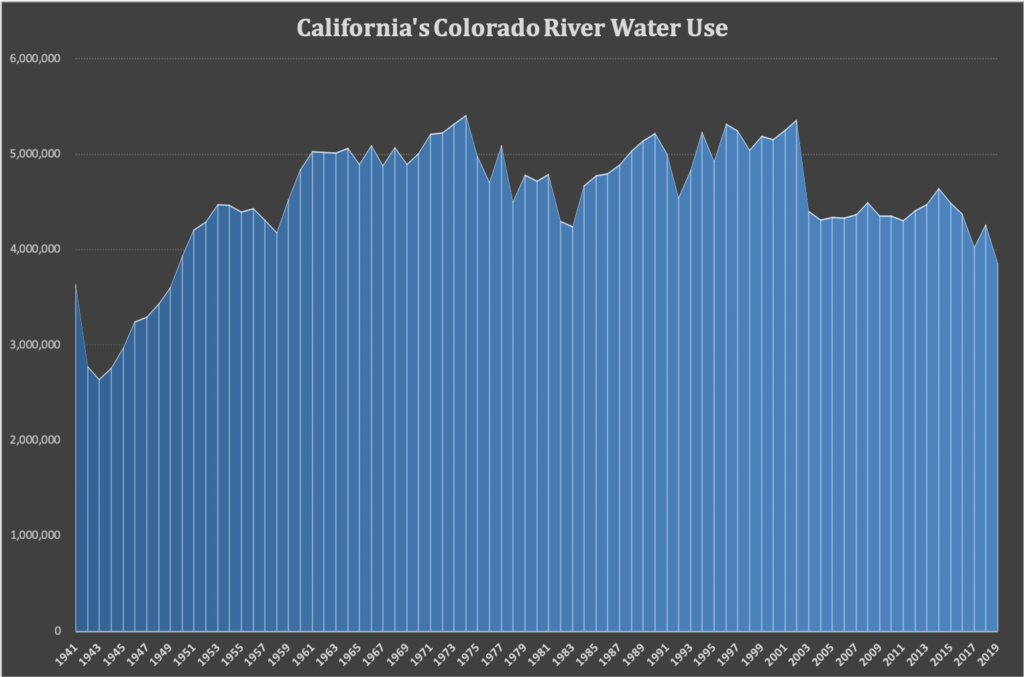

Mexico’s water agency notified the U.S. government that it wanted to cut its releases this month and store water in Mead, something that would have been impossible under the rules ten years ago. As I’ve written before, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California will take less water out of Mead in 2019 than it has in any year since the 1950s.

The result is that the Bureau’s current operating plan calls for releasing just 225,000 acre feet of water from Lake Mead in December 2019. I went back through a decade of USBR records (more research clearly needed, this is fascinating!) and that is by far the lowest December release I found.

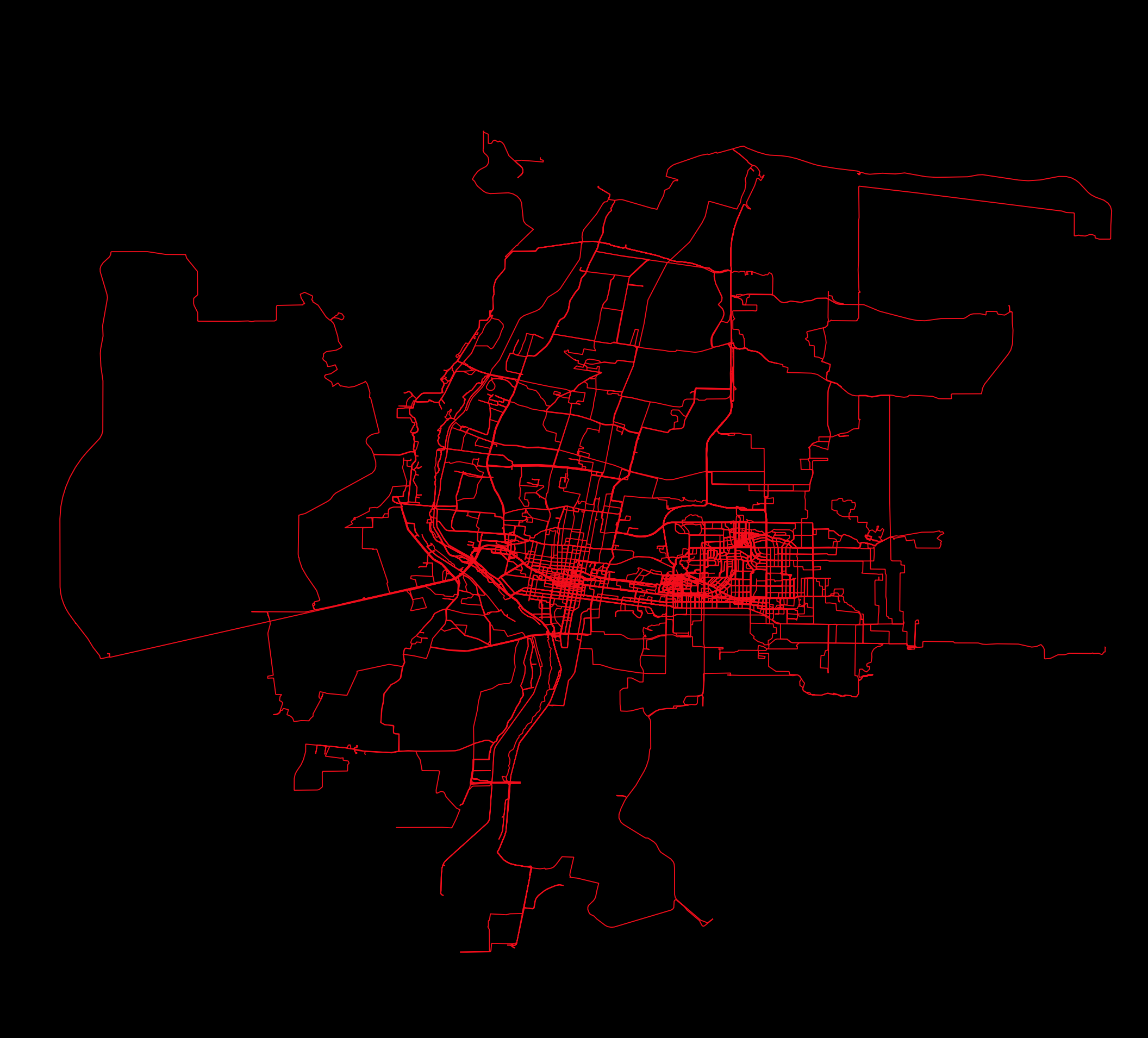

The idea behind “Hoover Down” is that the dam acts as a funnel that translates rules into moving water. Downstream, that water spreads out across the landscape. As the rules change, the volume of water flowing through the dam changes, and the landscape from Hoover down – not just the river corridor itself, but all the places beyond that use its water – changes as well.

There are a lot of places I could tell this story. I’m thinking about “Hoover Down” in significant part because of my love for that part of the Colorado River Basin – the basin of my childhood.

CRWUA – hitting “pause”

Friday’s tour was a coda to last week’s meeting of the Colorado River Water Users Association. Rules were the primary focus of the discussion, and a part of the work for “Hoover Down” will involve a close examination of the work over the next “n” years on a new, or newly revised, set of rules for how much water enters and leaves Lake Mead. The value of “n” itself is an interesting uncertainty in the whole thing. This book may take a while.

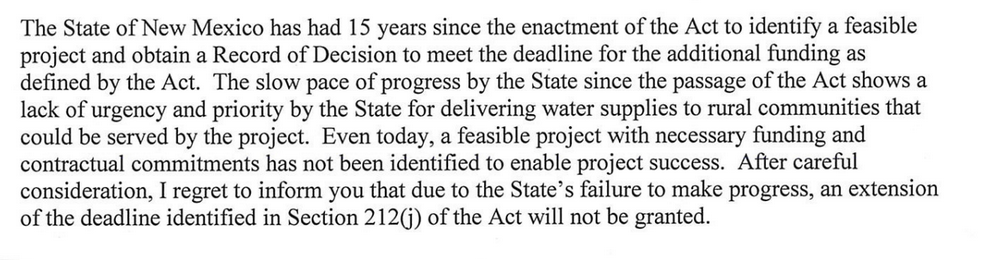

It was a “no big news” CRWUA, the kind where I was glad I wasn’t a beat reporter any more having to gin up a quick story. Ian James (who also joined the tour) turned a nice daily that focused on the key element. Rather than quickly going on to the next phase of “Law of the River” negotiations, Interior is hitting the “pause” button for a year long review of how the current river rules are working.

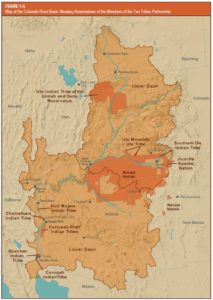

Speaking on the day’s final session, Interior Secretary David Bernhardt emphasized some interesting points, including the need for the next round of “Law of the River” negotiations to include Native American and environmental NGO interests. An Interior Secretary CRWUA speech is about signalling – that was a particularly important signal. How it translates into action remains to be seen, but the marker has been very publicly placed on the board.

As I think back to book two in “the series”, about how the network functions both formally and informally, I’m intrigued by the way the pause creates some space for informal discussions about what folks want the next round of rule discussions to look like and include.