Downtown Albuquerque at Dawn

Downtown Albuquerque at dawn – gulping its first breaths, hunting a breakfast burrito and a cup of coffee – is one of my favorite Albuquerques.

Downtown Albuquerque at Dawn

Downtown Albuquerque at dawn – gulping its first breaths, hunting a breakfast burrito and a cup of coffee – is one of my favorite Albuquerques.

From Janet Wilson at the Desert Sun:

The Colorado River Board of California voted 8-1-1 Monday to sign on to a multi-state drought contingency plan, which, somewhat ironically, might not be needed for two years because of an exceptionally wet winter.

The process was fractious until the very end, with blistering rebukes from the river’s largest water user, and charges that state and federal laws were possibly being violated to cross the finish line. The Imperial Irrigation District, a sprawling rural water district in the southeastern corner of California, refused to sign on until the federal government pledged to provide $200 million to clean up the Salton Sea, which has not occurred.

The paperback looks a lot like the hardback, but it has a new afterward!

Publishing a book is a weird exercise in time shifting.

Last fall, I was finishing Science be Dammed, the new Eric Kuhn-John Fleck book, while simultaneously working on a new afterward afterword to Water is for Fighting Over, out in paperback, well, tomorrow.

My friends at Island Press helpfully reminded me this morning that it would be good to reach out to y’all and encourage you to buy the paperback, so consider that box checked. But it’s also nice moment to catch my breath and reflect on what it is I’m doing here, and why.

Last fall was a tough time in the Colorado River Basin. Coming off of a very bad water year, nerves were fraying, deals were collapsing, and it very much looked like the rosy scenario I had sketched in Water is For Fighting Over, a story about our ability to solve problems, was in doubt.

As I turned to my brain trust to talk about what was happening on the river, I asked the same question over and over: “What should I write in the new afterward? Am I optimistic or pessimistic?”

At one point – we were at a reception at Hannah Holm’s wonderful Upper Colorado River water forum – one of my smartest river friends looked at me hard and said, bluntly, “John, you have to be optimistic.” Her point was not that optimism was right, but that someone has to frame this with an optimistic narrative, to help model what a good outcome might be.

Steven Pinker has tried unsuccessfully to coin a new word for this thing that I do – “possibilism“. It rightly hasn’t caught on – it’s a terrible word. But it nicely captures what this exercise of mine is about.

Water is For Fighting Over was about what a successful Colorado River, western water process might look like, based on storytelling, backed by numbers. It was a description of where our adaptive capacity might come from, what it might look like.

Science be Dammed is a chronicle of many of the mistakes that were made in the use of science on the Colorado River, mistakes that created much of the mess that we’re in now. But it too is “possibilist”, suggesting a path to solve problems by better use of science in the future.

And the new afterward afterword to Water is For Fighting Over remains cautiously optimistic. I hope you enjoy it.

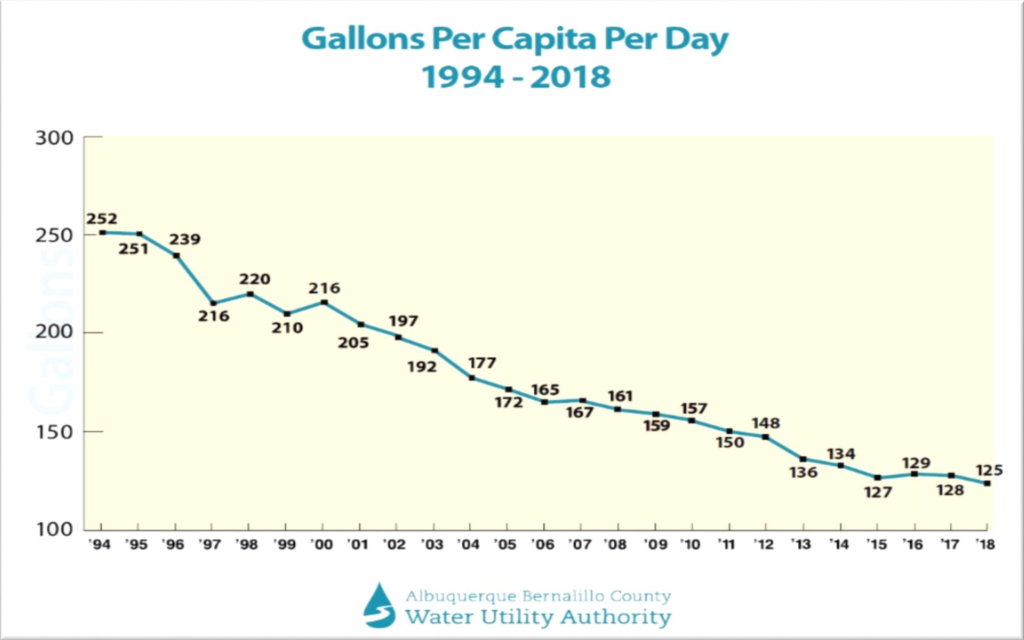

Albuquerque’s 125 gallons per capita per day cupcakes

Update based on questions on Twitter and in the comments: This number represents all Albuquerque municipal water use – residential, commercial, parks, system losses, etc. Frequently per capita usage numbers quoted are for residential use only, so beware apples-oranges comparisons.

Previously: There were cupcakes on a table by the door at the most recent meeting of the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority: “125 GPCD”.

I have some schtick in my standard water talks: “Albuquerque has, since the mid-1990s, cut its per capita water use nearly in half.” That’s a pretty remarkable thing – a large community cutting its per capita use of a critical resource nearly in half, with no ill effects, in a bit more than two decades.

Now, I can drop the “nearly”. The 2018 numbers are in, and we’ve reached 125 gallons per capita per day.

Courtesy Carlos Bustos, ABCWUA

When I was covering this stuff for the newspaper, I was a skeptic. As I talk about in the first chapter of my last book, I was steeped in the “tragedy narrative” I learned from Marc Reisner and those who followed in his tradition. In fact, I was one of them:

Like many who manage, engineer, utilize, plan for, and write about western water today, I grew up with the expectation of catastrophe…. [A]s drought set in again across the Colorado River Basin in the first decade of the twenty-first century, I was forced to grapple with a contradiction: despite what had Reisner taught me, people’s faucets were still running. Their farms were not drying up. No city was left abandoned.

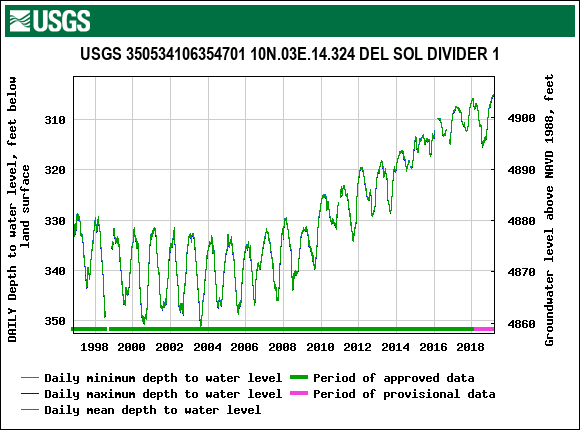

I didn’t talk about it in the book, but one of the keys for me was Albuquerque’s aquifer. As we pushed the conservation above – along with a significant supply shift to make use of our imported Colorado River water – our aquifer began to rise.

USGS groundwater measurements, Del Sol Divider, Albuquerque, New Mexico

Our water use is down, our aquifer is rising. And we’re still meeting our legal delivery obligations to Elephant Butte Reservoir under the Rio Grande Compact. The system is not only in balance, net storage here is going up.

I know, I know, past performance is no guarantee of future results. Things get harder, not easier, with a growing population and a warming climate. But we’re doing pretty well.

Have a cupcake.

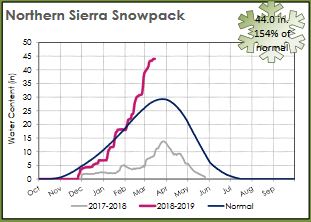

The booming Rocky Mountain snowpack has eliminated the risk of a formal Lake Mead “shortage” declaration in 2020, and has substantially reduced the risk in 2021, according to the latest Bureau of Reclamation 24-month study. More importantly, in my view, is the reduction of a longer term risk of a legal battle over the Upper Basin’s Mexican Treaty delivery obligation.

The current forecast calls for Mead ending 2019 at elevation 1,080, five feet above the threshold at which a set of rules previously developed by state and federal governments would have reduced allocations to Arizona, Nevada, and Mexico. That is more than eight feet higher than the projected elevation just a month ago.

More importantly, the new projections suggest now that there will be another 9 million acre foot release from Lake Powell in 2020, rather than the 7.48maf 2020 release projected just a month ago. The result is a preliminary end-of-2021 Mead forecast 20 feet higher than was expected just a month ago:

Comparison between Lake Mead elevation forecast in February vs. March 2019

It’s that shift from a 7.48maf release next year to a projected 9maf release, the result of operating rules in the 2007 Interim Guidelines governing balancing the contents of Mead and Powell, that’s the huge deal here. It means the water users in the Lower Colorado River Basin will continue to get extra water, above and beyond their legally expected 8.23maf releases each year. If this forecast holds, it would mean that since 2011, the Upper Basin would have delivered an excess of at least 9.4 million acre feet, above and beyond the legal requirements of the Colorado River Compact.

A series of 7.48maf releases from Powell – possible under the current operating rules if we were to have really bad Upper Basin hydrology – would have put us into dangerous legal territory, in terms of how the rules governing water delivery obligations under the Mexican treaty are interpreted. One of the basin’s unresolved legal questions is the extent of the Upper Basin’s obligations to deliver half of the water needed to meet the U.S. obligation to deliver 1.5maf per year to Mexico. A series of 7.48maf release years could have forced a legal test of that question, which is one of my “how the legal system could crash” fears.

This year’s snowpack seems to have significantly reduced that risk for the foreseeable future.

One of the many reasons the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California interests me so much is the way that it integrates much of the complexities of water management in the western United States. By drawing supplies from the Sierra Nevada as well as the Colorado River Basin, it links the two largest arid-west ag-urban water management complexes. It is, for better or worse, a fulcrum.

Right now, it’s on the “better” side of the fulcrum. Met’s latest “Water Supply Conditions Report” is a remarkable thing to behold. First, the Northern Sierra Nevada:

Northern Sierra Nevada, courtesy MWD

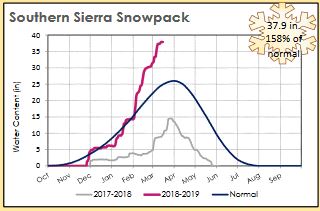

Next, the Southern Sierra:

Southern Sierra Nevada, courtesy MWD

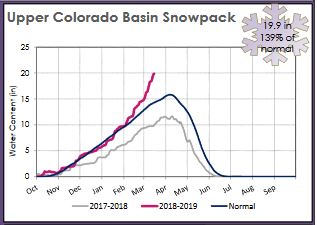

And the Colorado River Basin:

Colorado River Basin, courtesy MWD

You can see why Met is feeling the flexibility right now to make the contributions it’s offering to the Colorado River Drought Contingency Plan.

If, as being widely reported, the Colorado River basin states (and the major water agencies that largely dictate what the states do) ultimately decide to proceed with a Lower Colorado River Basin Drought Contingency Plan that cuts out the Imperial Irrigation District (IID), no one should be surprised. It’s simply continuing a long, and perhaps successful, tradition of basin governance by running over the “miscreant(s)”.

The tradition started with the ratification of the 1922 Compact and the authorization of the 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act (which authorized Hoover Dam and the All-American Canal). Arizona, led by colorful governor George P. Hunt, opposed the ratification of the compact. So what did the other six states do? They designed a six-state approval strategy and implemented it through the passage of the 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act, which Arizona opposed but could not stop. By the 1940s when the basin’s attention had turned to the Mexican Treaty, Arizona had joined the compact club, ratifying it in 1944. The outliers were now California and its nominal ally Nevada. Both states opposed the Senate ratification of the 1944 Treaty. Their fate was the same as Arizona’s in 1928, led by the other five basin states and Texas (the 1944 Treaty includes the lower Rio Grande), the Senate easily ratified the treaty.

In the 1950s as Congress turned its attention to passing the Colorado River Storage and Participating Projects Act (CRSPA authorized Glen Canyon Dam and a bunch of other Upper Basin projects), the states were aligned 6 -1 with California again on the outside (by then Nevada had joined the other five states). The outcome was the same. Congress and the Eisenhower Administration ignored California’s spirited opposition and CRSPA easily passed. Similarly, Arizonans argue that they were forced by California and the other states to accept the Central Arizona Project’s junior status in return for their support for its authorization in 1968. (The alternate story and actual reality is that Arizona and its CAP boosters understood that the junior status was the logical outcome of Arizona’s 1964 victory in AZ v. CA and put the junior priority on the table upfront before any Congressional debate.)

In 1970 it was the four states of the Upper Division that got to feel the tire tracks. The subject was the operation of Glen Canyon Dam. The four upper river states were strenuously opposed to an annual minimum objective release of 8.23 million acre-feet per year because it arguably included an Upper Basin contribution of 750,000 acre-feet per year for Mexico (1/2 of the 1.5 MAF annual treaty delivery). The outcome was eloquently described by legendary New Mexico State Engineer Steve Reynolds as “they (the Lower Basin and Secretary Walter Hickel) crammed it down our #%&@#$ throats!” The obligation of the Upper Basin to Mexico under the 1922 Compact is still an unresolved issue.

Thus, if the rest of the basin decides to move ahead with DCPs without the cooperation and participation of IID, it will continue a long tradition and one that many argue has benefited the basin as a whole. The major difference between the past and now is that in past decisions to overwhelm opposing states or major agencies, the issue was primarily the development of new projects. Today, with an overused river, it’s about the reallocation of water between those with senior rights (primarily agriculture) and those with junior rights but in need certainty of supply – the large urban centers that use Colorado River water.

In our new book Science be Dammed, John Fleck and I argue that the beauty of the 1922 Compact was that it was a social contract between the faster growing states on the lower river (primarily California) and the slower growing states on the upper river to leave some water in the river for their future development. This allowed the states to cautiously form the coalitions necessary to pass the federal legislation needed to develop the river. As we have seen, for the major decisions there was rarely unanimous agreement. Today, in an era of reallocation of existing supplies, what is needed is a similar social contract between the haves, the rural areas of the basin that rely on agriculture (with senior rights), recreation and a healthy river and the have-nots, the urban centers with mostly junior rights, but with a need for certainty of supply and the political and economic power to overwhelm the rest of the basin. The goal of such a social contract would be to allow the inevitable reallocations, but only if there is a clear and real benefit to the areas-of-origin.

Leaving IID out of the Lower Basin DCP might make sense for a number of good reasons (especially with the great snowpack which reduces the risk faced by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California in shouldering the DCP burden without IID’s help), the question policy makers should consider is in the long run (post 2026 for the Colorado River Basin) is such an action going to make it easier or harder to manage conflicts on a shrinking river?

Driving between old Mesilla, New Mexico, and the Rio Grande this evening after dinner, Lissa and I saw a bunch of new pecan orchards going in.

We took last minute advantage of university spring break to head south. We spent some time wandering around looking at and thinking about the border, and also driving the roads of the Rio Grande valley floor as it spreads out south of Elephant Butte Reservoir on its way to El Paso and Juarez.

Both things are, in very different ways, examples of the way human institutions shape landscapes on a grand scale. With the new book done, we’re in the calm before the new book storm, and I’ve been thinking back to an idea I’ve had for some time about at thing to write. I’m not quite sure how to explain it, but involves the way what economists would call “exogenous forces” shape landscapes.

In the borderlands country, we’ve got the obvious case of a relatively arbitrary decision nearly two centuries ago to draw a line on a map in a particular place and a particular way that gives us this:

El Mesteño Cattle Co., Santa Teresa, New Mexico, USA

On the left is the El Mesteño Cattle Co. The thing in the middle is the U.S. Mexico border, I guess you’d call that a “fence”. Across the fence is El Mesteño’s counterpart in Mexico. It’s a transboundary cattle shipping point, in the middle of the desert.

Landscape, shaped by rules.

The border was more than a little uncomfortable, so Lissa and I dropped back down into the Rio Grande Valley and drove through miles and miles of pecan orchards, landscape shaped by a different set of exogenous forces.

Down a side road through magnificent, lucrative groves, we came upon this:

Mesilla Dam

If you peer through the graffiti, you can see the “USRS 1915”. The U.S. Congress in 1902 passed the Newlands Act, which created the U.S. Reclamation Service (now the Bureau of Reclamation). In the teens, the Reclamation Service built the Rio Grande Project, which controlled flooding and distributed irrigation water to the Mesilla Valley. (The sand, you’re wondering. They turn the river off here over the winter, and haven’t turned it back on yet for spring irrigation season.)

The result today is forests of pecan trees, at this point more than 30,000 acres and growing. Among the exogenous forces shaping this forest is a set of rules that permits groundwater pumping when surface water flows are scarce, as they have been in recent years. Among the countervailing ecosystem pressures, if one could think of them that way, is a lawsuit by Texas, against New Mexico, arguing that the groundwater pumping violates the Rio Grande Compact’s water delivery rules.

countervailing ecosystem pressures here

A couple more threads here.

Pecan acreage here is up, from 24,000 in 2010 to 33,000 in 2018. Alfalfa, meanwhile, is down, from 30,000 acres in 2010 to 15,000 acres in 2018. As surface water grows scarce, groundwater pumping is expensive, pecans are lucrative, alfalfa is not. (This, at least, is my hypothesis. More study is needed.)

pecans

Exogenous forces, shaping landscapes. There’s a story here somewhere.

The Desert Sun’s Janet Wilson has an important update on progress toward a Colorado River water use reduction plan – the poorly named “Drought Contingency Plan”:

With a Monday deadline looming, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California has offered to break an impasse on a seven-state Colorado River drought contingency package by contributing necessary water from its own reserves on behalf of the Imperial Irrigation District. It’s not help that IID is seeking, but Metropolitan general manager Jeffrey Kightlinger said he had no choice.

Now that Arizona finally seems to have its act together, the Imperial Irrigation District has become the lone holdout in piecing together the DCP. Behind the scenes, Met has been putting together its own Plan B: a DCP in which Met makes all the California contributions itself rather than having the deal depend on 250,000 acre feet from IID.

This suggests something fascinating. After some real struggles in the early 2000s as Met was forced to reduce its water use as California cut its Colorado River water use from 5-plus million acre feet per year to 4.4 million acre feet per year, Met is now acting like it thinks it has plenty of water – or at least, enough to shoulder the DCP burden without Imperial’s help.

Editor’s note: This is the first post by Eric Kuhn, former general manager of the Colorado River Water Conservation district and the co-author, with Inkstain’s John Fleck, of the forthcoming book Science Be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River, to be published this fall by the University of Arizona Press.

By Eric Kuhn

There has been considerable media attention to the travails within Arizona and California as water agencies work to complete the intra-state agreements so that along with Nevada, the three states of the Colorado River’s Lower Division can implement their drought contingency plan (DCP). While there has been coverage of the juicy details of the day-to-day negotiations, less attention has been given to the more basic question: Why does the Lower Basin even need a DCP?

The most common answer to this question largely parrots the talking points of the basin water community – since 2000 the basin has experienced an unprecedented drought causing reservoir levels to plunge to unacceptably low levels, therefore we need to be prepared for deep cuts to our water use in the event the drought continues. While this answer is partially true, it avoids important details that many basin water managers would rather be kept out of the public dialogue.

For nearly a hundred years experts have been warning the basin that ultimately water users in the Lower Basin would be facing a structural deficit of at least 1.2 million acre-feet per year. The math is quite simple: When the Upper Basin is only making the releases required by the 1922 Compact, inflow to Lake Mead is about 9 million acre-feet per year; 7.5 million for the Lower Basin, a disputed 750,000 for Mexico, and about 750,000 of inflow between Lee Ferry and Lake Mead. However, uses from Lake Mead, without additional conservation, average about 10.2 million acre-feet per year; 7.5 million for the three Lower Division states, 1.5 million for Mexico, and about 1.2 million acre-feet of reservoir evaporation and system losses. Thus, outflow exceeds inflow by about 1.2 million acre-feet per year, now commonly referred to as the “structural deficit.”

A structural deficit of more than a million acre-feet per year was first predicted by USGS hydrologist Eugene Clyde LaRue in the early 1920s. In the 1960s Upper Basin water engineer Royce Tipton told Congress that once the Central Arizona Project was operational, the Lower Basin would have a deficit of 1.2 to 1.9 million acre-feet per year depending on the Upper Basin’s actual obligation to Mexico. So why has the basin waited until now to put in place a serious plan for living within its means?

The Colorado River system is primarily managed under what is referred to as the 2007 Interim Guidelines, a set of rules that defines annual releases from Glen Canyon Dam and the deliveries of water from Lake Mead to users in the Lower Basin, including the shortage criteria. The Interim Guidelines were negotiated by representatives of the basin states and the Secretary of the Interior in the early 2000s. At the time the negotiations commenced in 2005, the basin was dealing with the impacts of the exceptionally dry 2000-2004 period. There was no doubt that the Lower Basin needed shortage criteria and there was little debate that the Secretary of the Interior had the authority to impose shortages pursuant to the 1964 decree in AZ v. CA. The questions were when would shortages be triggered, how big would they be, and because of the Central Arizona Project’s junior status, what level of shortage would Arizona accept before it decided to plunge the basin into litigation rather accept consensus criteria?

The end-product that Secretary Kempthorne signed in early 2007 included many compromises. Even though it was well understood that at least 1.2 million acre-feet of cutbacks would be needed to stabilize Lake Mead during an extended drought (or under the reasonably foreseeable impacts of climate change which were well documented by 2007), the 2007 shortage criteria were limited to 600,000 acre-feet per year, which included participation by Mexico, only about half of what was needed. Additionally, the 2007 guidelines have a provision that precludes agencies, such as MWD that fund conservation measures and bank the saved water in Lake Mead, from actually using the saved water during a declared shortage. The provision is a little like suggesting families have emergency saving for an unexpected income loss, but not allowing them to use it when it happens. However, in hindsight, Arizona’s strategy worked. Under the proposed Lower basin DCP, California, even though not required to do so by the 2007 Guidelines, has offered to participate in additional shortages.

In short, the proposed Lower Basin DCP completes the job the 2007 Interim Guidelines process began, but due to politics, could not fully accomplish. Under the proposed Lower Basin DCP, when Lake Mead drops below critical storage levels, the total cutbacks exceed 1.2 million acre-feet, enough to stabilize storage, and entities like MWD that have banked water in Lake Mead, as a drought reserve, will have access to this water when it is truly needed.

What the Lower Basin DCP does not accomplish is to provide a framework to address a continuing decline in the long-term average flow of the river caused by climate change induced aridification. That will have to wait for the next round of negotiations, beginning soon, to replace the 2007 Interim Guidelines with rules that will manage the river after 2026.