From the inbox:

From the inbox:

There is an Air Force Base on Albuquerque south side. It has contaminated our aquifer. The relationship between the community and the Air Force regarding cleanup has been rocky.

More rocks:

ABCWUA press release regarding Kirtland cleanup

Deep in the copy edits for our new book, Eric and I have stumbled into this minor obstacle:

Mainstream, main stream, mainstem, or main stem??? The Supreme Court commonly used mainstream in its 1963 AZ v CA decision – Now Merriam-Webster appears to have taken the word away from rivers. @jfleck and I use main stem in Science Be Dammed UofAZ Press Fall19

— Richard Eric Kuhn (@R_EricKuhn) April 15, 2019

It’s a fascinating reminder of the way the words of water are everywhere, carrying their separate linguistic cargo. And, thanks to the modern technology of search-and-replace, it is a problem easily solved.

Rio Grande overbanking, Albuquerque, April 11, 2018

My “job”, as director of the University of New Mexico Water Resources Program, requires me to pay close attention to New Mexico’s water. So of course when I saw this morning that the Rio Grande’s flow through Albuquerque had topped 2,500 cubic feet per second, I had to conduct “field work”. Anything above 2,300 cfs right now and the water begins spilling through engineered cuts like this in the river’s bank into backwaters created to simulate natural “overbanking”. This spot just happens to only be accessible via a bike trail, so I simply had no choice but to go on a bike ride.

Best part – the cormorant, fishing where the ag outflow enters the river:

Cormorant fishing at a Middle Rio Grande ag water outfall, Albuquerque, NM, April 11, 2018

It’s important to be clear of what we mean by “waste” when we talk about “wasting” water. Because it’s always going someplace, and doing something.

In Albuquerque, for example, we talk about reusing effluent from our sewage treatment plant. But we currently treat that water and put it back in the Rio Grande, where it supports riparian habitat and downstream water users. To them, it’s not being “wasted”.

Luke Runyon at radio station KUNC in Colorado did a great piece on the Ciénega de Santa Clara, in the Colorado River’s former delta, that illustrates the point. “Waste” water from agricultural practices in the United States was for decades diverted through a canal onto the mudflats where the Colorado River used to meet the Sea of Cortez. There, a fabulous wetland emerged, some of the best habitat of its sort remaining in the desiccated region.

But with pressure to stop “wasting” that water, the Ciénega is in perpetual peril:

As the Colorado River basin heats up and dries out like climate projections predict, Butrón-Méndez is concerned people will stop thinking of the water that flows to the wetland as waste, find a way to use it and, in turn, harm the Ciénega.

A cryptic item in the agenda for Thursday’s meeting of the San Diego Water Authority Board suggests the agency may still harbor an interest in having its own canal to the Colorado River, separate from the current system through which it gets its Colorado River water from the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California.

SCDWA board memo, April 11, 2019

There is history here. In 1934, San Diego signed its own contract with the federal government for Colorado River water. (The episode merits a footnoted digression in our new book, though the episode is an obscure enough piece of Colorado River history that I had to call my co-author, Eric Kuhn, who wrote the footnote, to refresh my memory. No episode is so obscure that it slips Eric’s memory.)

The original plan was for a “San Diego aqueduct”, an extension of the All-American Canal, which currently carries water to farms in the Imperial Valley. As detailed in the 1948 Hoover Dam Documents, the canal was superseded during the 1940s by the construction of an extension of the MWD system, something deemed a military necessity because of San Diego’s critical role as a Navy base during World War II and, presumably, the Cold War that was revving up thereafter. Contracts were changed, big checks were written by the federal government, and San Diego became tethered to Met’s system from the north, rather than to the All-American Canal to the east.

Over the years there also have been discussions of San Diego connecting via Mexico’s plumbing that currently brings Colorado River water to Tijuana. That also could be, in the language of the SDCWA staff memo, “alternative conveyance”.

We have a publication date and a web site and an Amazon listing for Science Be Dammed, the new book by Eric Kuhn and myself about the use and misuse of science in the development of the Colorado River. And a cover. The book has a cover:

Coming Nov. 26, 2019

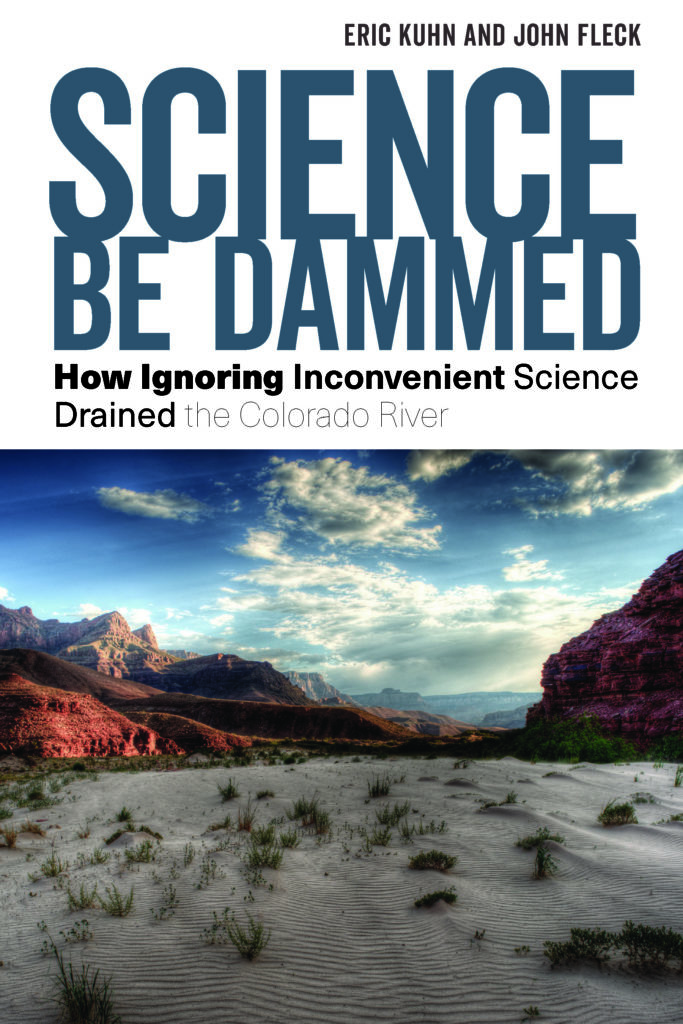

The Colorado Basin River Forecast Center’s April 1 forecast is up 1.9 million feet from a month earlier. How to think about how much water that is?

CBRFC April 1 2019 forecast

A friend who thinks a lot about water and public communication, but who is not from the Colorado River Basin, was commenting recently on our euphemisms – the “structural deficit” in particular. For those not familiar with the term, it is the amount by which the Lower Colorado River’s water is overallocated. The system’s “paper water” – allocations handed out in the system’s rules – is 1.2 million acre feet greater than the actual available “wet water”.

Seeing our language from the point of view of a smart outsider was helpful, and gave me pause. I ultimately had to agree that structural deficit was a) a euphemism that doesn’t work at all well in communicating with the general public, and b) an incredibly useful language tool for the informed Colorado River community.

The alternative language, still commonly used, is “drought”. But drought offloads the responsibility to climate. “Structural deficit”, for those thinking hard about the river, moves the problem back within water management accountability. The difference involves which audience you’re speaking with.

Since I presume anyone patient enough to stick with my blog blathering this long is likely a member of “b”, I’ll double down on “structural deficit” for you.

The increase in the March forecast is equal to ~1.6 Structural Deficits.

Manny Teodoro, a Texas A&M researcher who’s been doing important work on municipal utility governance and rate structures, has an update today on the 2018 California water conservation data.

Point one, which is important given some breathless and totally premature journalism last year about California’s water conservation post-Big Drought, is that municipal water use remains lower than the 2013 benchmarks when the state began its aggressive statewide mandatory water conservation efforts. Even as drought pressure has abated, conservation behavior has stuck.

Point two is that private utilities continue to perform better than public utilities in terms of conservation:

Overall urban water use remained significantly lower in 2018, with average monthly conservation of about 14% compared with 2013. The public-private disparity in overall conservation also persisted.

This seemed counterintuitive to me when I first came across Teodoro’s findings. But his explanation makes sense, and is consistent with other research suggesting a connection between governance structure and water conservation performance. His essential argument is that municipal management, more directly accountable to voters, faces, in his words, “political headwinds” in implementing things like rate hikes and mandatory watering restrictions. Private utilities, accountable to state regulators rather than local voters, have a relatively easier time of implementing such measures, he argues.

Tuesday was a remarkable day for Colorado River Basin governance.

With the kinda sorta now approved Drought Contingency Plan, we have the first formal commitment from the basin states to quantified water use cutbacks of more than a million acre feet per year as Lake Mead drops. With important caveats, this is enough to stabilize the reservoir.

This is arguably the most important milestone in river management since the early 2000s.

The last-minute deal cut out the Imperial Irrigation District and, in the process, Imperial’s claims and concerns about the environmental and health quality problems associated with a shriveling Salton Sea. There is blame to go around for this messy end, but at its root it is a profound failure of Colorado River Basin governance. One of the most important side effects of our efforts to reduce Colorado River water use over the last two decades, a problem that affects a lower income Hispanic community, was formally, visibly, and explicitly left out of the decision at the 11th hour.

Depending on what happens next, this could become a singularly important element of the above mentioned “most important milestone in river management”, and not in a good way.

At a talk during the 2013 meeting of the Colorado River Water Users Association, Arizona’s Tom McCann presented this slide:

It’s a pretty striking visual, given the assumptions that went into it.

This is not a measure of the impact of drought or climate change shrinking Lake Mead. This graph assumes that the states of the Upper Basin are meeting their full legal obligations under the Colorado River Compact, plus delivering half of the U.S. obligation to Mexico under the 1944 treaty. This is simply water balance arithmetic, a “structural deficit.” Given the structure of the Colorado River allocation rules and full Upper Basin deliveries:

Given that reality, as the Bureau’s Terry Fulp said in my last book, “Lake Mead will go down.” The math here is not hard.

It also is not hard, in principal, to see what is needed to fix it. Use less water. DCP does that.

Under DCP, the states (and Mexico, under a companion agreement) have agreed to a series of cutbacks as Lake Mead drops that would slow its decline and, when it reaches an elevation of 1,030-1,040 feet above sea level, would fully meet the 1.2maf “structural deficit”, as Tom described it in 2013.

Rather than trying to cling to their Law of the River-promised paper water allocations and lawyering up, water users of the Lower Basin have collectively agreed to reduce their use by more than a million acre feet per year.

This is a striking confirmation of the central hypothesis of my last book – that we have entered a new era of collaborative governance on the Colorado River, that water is no longer for fighting over.

But clearly we also have, as you can see in this from Desert Sun’s Janet Wilson, a counter-argument against my collaborative governance hpothesis:

“I have six grandchildren who live on the Salton Sea and five of them have asthma. On behalf of them, I say, ‘Damn them. Damn them,’” said IID board member Jim Hanks.

“As we gather here today on the shore of the Salton Sea strewn with bleached bones, bird carcasses and a growing shoreline,” Hanks said, “and as champagne is being prepared for debauched self-congratulation in Phoenix, remember this: The IID is the elephant in the room on the Colorado River as we move forward. And like the elephant, our memory and rage is long.”

The linked story by Wilson and the Arizona Republic’s Ian James explains the background, but in short the Imperial Irrigation District made a last-ditch effort to condition its participation in DCP on federal funding to help mitigate environmental and public health problems associated with the Salton Sea. In a push to get the deal done California’s other Colorado River Water users, led by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, cut IID out of the deal and forged ahead without them.

In conversations with Colorado River leadership over the last week, I’ve heard a combination of sympathy for the stance taken by Hanks and his colleagues and frustration with the way Imperial handled the whole affair.

The process by which California worked out the details of its DCP agreement was relatively opaque, so it’s hard for those of us on the outside to understand exactly how this happened. Clearly until late last year, the Imperial Irrigation District was generally supportive of DCP, negotiating some valuable benefits – new water management flexibility and the ability to bank water in Lake Mead. Those things would have been of great benefit to Imperial and the rest of the basin. We all thought IID was on board.

The pivot in late 2018, with the added demand for money from the U.S. Department of Agriculture for Salton Sea mitigation, left a bunch of DCP negotiators frustrated. So I guess blame on Imperial here for not making more clear from the beginning what it needed from a DCP.

But there is a deeper issue here for which California’s entire Colorado River water management community, and perhaps the entire Colorado River Basin water management community, is to blame as well. The problems of the Salton Sea are in significant part the result of decisions made in the early 2000s to begin bringing the Colorado River Basin’s water use into balance through reductions in Imperial. It was clear even then that one of the consequences would be a shrinking Salton Sea, with environmental and public and public health effects. Commitments were made by the state of California that haven’t been kept.

The benefits of Imperial’s water use reductions accrued to all of us – certainly to California, but also to the rest of the basin. Dealing with the resulting Salton Sea problems has been left to Imperial to push for and sort out. Imperial had to bargain away other benefits it might have wanted to get the Salton Sea dealt with. This is why, sitting in my university office in far-off Albuquerque, I was cheering on Jim Hanks. As I wrote in the Sacramento Bee two years ago, “To solve the West’s water problems, California needs to solve the Salton Sea.”

It shouldn’t be Imperial’s responsibility to solve the Salton Sea, it should be all of our responsibility.

My co-author Eric Kuhn has been making the argument that the next steps in Colorado River Basin governance require a new rural-urban social contract. What just happened seems a huge step backward in that regard. As Eric wrote here a couple of weeks ago:

Leaving IID out of the Lower Basin DCP might make sense for a number of good reasons (especially with the great snowpack which reduces the risk faced by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California in shouldering the DCP burden without IID’s help), the question policy makers should consider is in the long run (post 2026 for the Colorado River Basin) is such an action going to make it easier or harder to manage conflicts on a shrinking river?

On balance, I think it was a good week. We got a DCP, with commitments to water use reductions that are sorely needed. And while Imperial didn’t get what it asked for, I hope we’ve all learned that we can’t solve the West’s water problems without solving the Salton Sea.