OK, “strategy” is not exactly the right word here, but we take our water conservation where we can find it, eh?

Luke Runyon took a nice dive into the water supply implications of the West’s wave of coal plant retirements. Because coal plants use water. Here’s my coauthor Eric Kuhn on the implications:

“As a legal matter, the owners of the water rights, at least in Colorado, could do something else with them. As a practical matter, there’s not much else they can do with them,” said Eric Kuhn, former head of the Colorado River District and author of Science Be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River.

TriState has limited options with the water rights, Kuhn said. The energy provider could sell them to a local municipality, though communities along the Yampa River, like Steamboat Springs, Hayden and Craig, likely wouldn’t be able to use that much water all at once. TriState could offer them to local farmers, though most of the easily irrigable land has already been irrigated for a long time. They could turn them into in-stream flows. Or they could sell them to a user outside the Yampa basin, like a Front Range city. Any project proposed to pump the plant’s freed up water more 200 miles eastward would face significant political pushback and a multi-billion dollar price tag, Kuhn said.

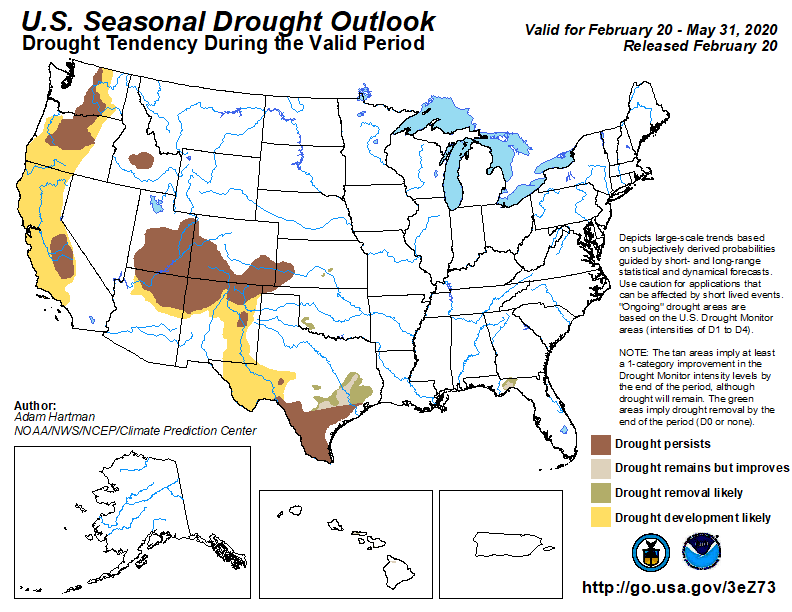

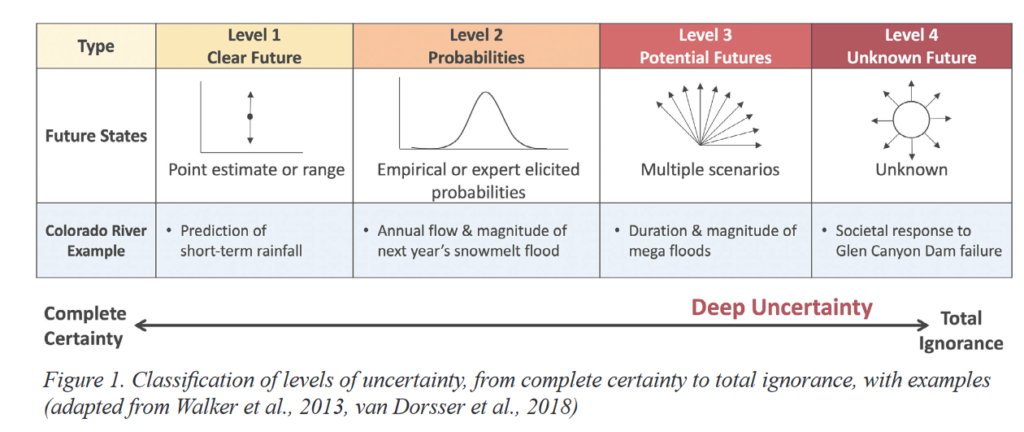

According to Kuhn, these coal closures also have implications for broader Colorado River management. The recently signed Drought Contingency Plans task water leaders in Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico to begin exploring a conceptual program called demand management, where in a shortage, water users would be paid to use less. Coal plants using less water would alleviate the situation.

“What it’s going to do is take the pressure off of these states to come up with demand management scenarios, because where does that water go? It’ll flow to Lake Powell,” Kuhn said.