[T]he anticommons refers to situations where there are numerous overlapping rights holders (or what might also be seen as numerous policy advocacy coalitions) each with some power to veto or block system or operation change. The tragedy emerges when the composite effect of such power prevents significant change in the system.

– Jones, Benjamin A., et al. “Valuation in the anthropocene: exploring options for alternative operations of the Glen Canyon Dam.” Water Resources and Economics 14 (2016)

Wandering the halls of Bally’s in Las Vegas last December, at the annual meeting of the Colorado River Water Users Association, I received a text from a friend with a link to a piece in Politico by Marc Dunkelman about the late New York power broker Robert Moses.

Robert Moses turning models into a reshaped city. Library of Congress. New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c36079

Dunkelman spins a wonderfully readable tale of New York’s Penn Station, in particular why it is so awful. Because despite everyone knowing this central Manhattan transportation hub needs to be fixed, and lots of people having good ideas about how to do it, and projects to carry them out, Penn Station remains awful:

In a dynamic where so many players can exercise a veto, it’s nearly impossible to move a project forward. No one today has the leverage to do what seems to be best for New York as a whole.

When I bumped into my friend later that day at Bally’s, I shared my puzzlement. Why was I being encouraged to read about Moses and Penn Station?

I have long argued that a robust governance network, both formal and informal, around the management of the Colorado River provides the necessary conditions for managing the problems of the river’s overallocation and the increasingly apparent impacts of climate change. That’s the argument at the heart of my last book, Water is For Fighting Over: And Other Myths About Water in the West

But as we approach the negotiation of the next set of Colorado River management rules – a process already bubbling in the background – it is not hard to see how my thesis could break down. The problem is an institutional structure that has distributed veto power across the Colorado River Basin.

I’ve been thinking a lot about my friend’s “read about Moses” tip in the months since CRWUA.

Moses, the “master builder” of modern New York who famously ran roughshod over – well, over everyone who didn’t agree with his sometimes troubling vision – left in his wake a reaction against such concentrations of power.

The progressive movement that arose in opposition created mechanisms to prevent another Moses from doing Mosesy things. Decades later, as Dunkelman documents, the veto points created to accomplish this reining in of power have made it impossible to fix Penn Station. While everyone agrees that the fixing is needed, lots of people disagree with the specifics of any one proposed fixed. And those people have a veto. So the fixing never gets done.

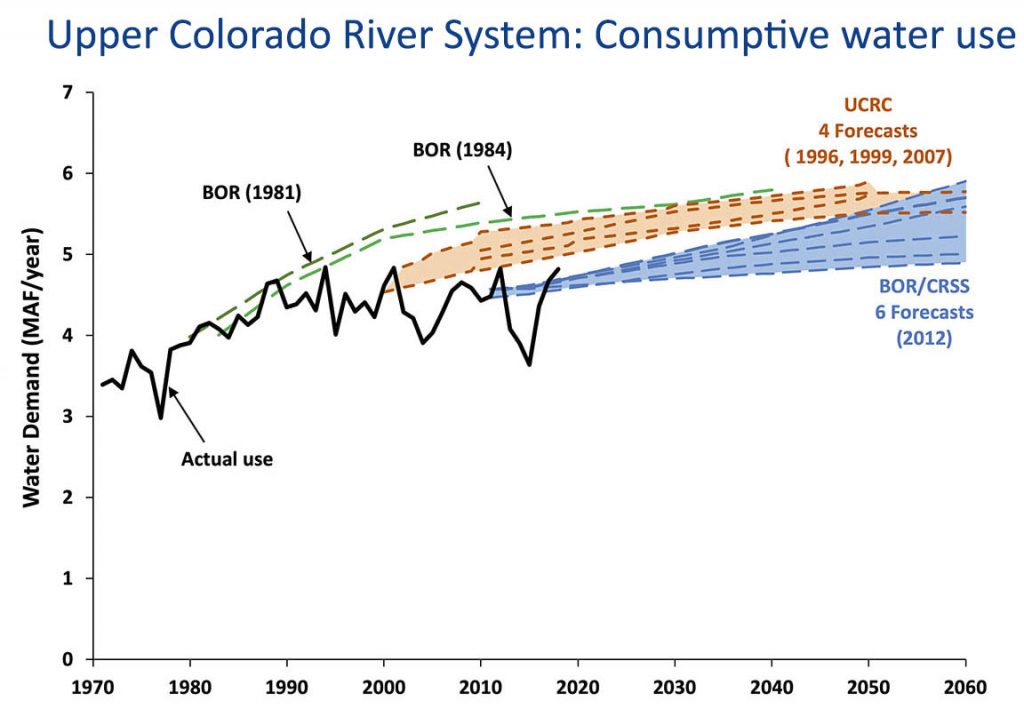

We have a similar problem in the Colorado River Basin. The river’s water allocation schemes are broken. Eric Kuhn and I spent a good deal of time laying out how that brokenness came about in our new book Science Be Dammed. We spent some time sticking our necks out with some of our ideas about what fixing it might look like. But as the discussions about a new river management ruleset bubble away, it is clear that we’ve got a problem very much like post-Moses New York: lots of people have a veto over any new scheme that we or anyone else might cook up.

The origins of the problem, in New York versus the Colorado River Basin, seem different. Where in New York the distribution of veto power arose in response to harms at Moses’s hands, in the Colorado River Basin the problems were baked in at the start. A federalism that left water management to individual states, combined with a compact that effectively gives each of the seven basin states (and, I guess, the federal government, and probably Mexico, and maybe going forward 29 sovereign Tribal nations, and increasingly an effective environmental community) a veto over any potential fix leaves us with a Penn Station-like gridlock. Here’s how I described the problem five years ago:

The first time I wrote about Terry Fulp, a key manager with the Bureau of Reclamation, I described him as “the closest thing we have to a guy with his hand on the tap that controls the vast plumbing system built over the past century to distribute the Colorado’s waters.” But I have come to realize in the years since I published that line in 2009 that, in reality, no one has their hand on the tap, and nobody has the ability to turn it down. Instead, we’ve built a decentralized system with no one in charge.

When I wrote that, I don’t think I full grasped the corollary – not only is no one in charge, but lots of people have the power to block solutions they don’t like.

After a talk I gave about the new book last week at the University of New Mexico School of Law, a student asked me the obvious question: We don’t we simply proportionally reduce everyone’s allocation to match hydrologic reality?

This of course makes perfect sense. But it is impossible in a system where major parties have deeply held views about fairness and equity and why they should keep their full allocation while those other people in that other place, who have been far less responsible, suffer the burden of shortage. And where the institutional structures effectively give all those parties a veto over such a solution.

University of Michigan legal scholar Michael Heller slapped a wonderful label on the problem some years back – “The Tragedy of the Anticommons“. I’m bending Heller’s original case to apply it here. But the idea of the existence of multiple veto points over solutions to commonly shared problems seems to hold, here and in many many other cases. (There has been a great deal of bending of Heller’s original anticommons idea since he first published it – it’s a pretty rich conceptual framework.)

My University of New Mexico colleagues Bob Berrens and Benjamin Jones are among those who have written about this in the context of Colorado River management (it was Bob some years ago who turned me on to Heller and the “anticommons” literature – Bob and Benjamin were writing the paper I link to at the same time I was writing Water is For Fighting Over):

[T]he anticommons refers to situations where there are numerous overlapping rights holders (or what might also be seen as numerous policy advocacy coalitions) each with some power to veto or block system or operation change. The tragedy emerges when the composite effect of such power prevents significant change in the system, and suboptimal use of limited resources. Like the better-known tragedy of the commons, the tragedy of the anti-commons also represents a coordination problem.

Jones et al (Bob and Benjamin and colleagues) suggest a path forward:

Governance processes for finding pathways through such coordination problems (e.g., to system operation changes), may benefit from improved information about the full range of preferences held across a population and argued in the policy domain. For example, broader system perspectives are more likely to find flexible least-cost alternatives to operational changes.

I don’t have an ending here. I’m not sure where to go with this.

The solution so far has been a series of incremental fixes that have avoided the risk of veto-triggering disputes. Maybe this argues for more of that – more incrementalism, rather than the sort of “grand bargainy thing” some of us have been advocating.