Longing for the day I need to carry a bike lock again.

Longing for the day I need to carry a bike lock again.

Morelos Dam, April 2010, by John Fleck

April 20, 2010, I took a drive that changed my life.

Around the back of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Yuma Area Office, helped by a map hand-drawn by Jennifer McCloskey, then the Yuma Area Office manager, I headed up a dirt road onto the levee that borders the eastern edge of the Colorado River as it makes its way south between the United States and Mexico.

Later that day, I headed north to Las Vegas. Always the storyteller in search of an angle, I walked after dark up to the strip to see the Bellagio Fountain. Here’s how I described it in a blog post time-stamped at 10:43 p.m. that evening:

LAS VEGAS, NEV – The distance between Morelos Dam on the lower Colorado and the Bellagio Fountain is profound. Morelos spans the U.S.-Mexico border, with the wheat fields and onions of the Yuma County Water Users Association behind me as I took this picture and Algodones on the far bank. Most years, Morelos is where the Colorado River effectively finishes its now futile run to the sea….

After some more stops to see the Lower Colorado’s plumbing, I made a beeline for Las Vegas. The contrast could not have been more stunning – up through the Sonoran and Mojave deserts, all mesquite and creosote, with occasional glimpses of the river strip in the distance, then through a ridge in the mountains, from quiet desert to this….

It is followed by the first of the umpty pictures I have taken in the years since of the Bellagio Hotel’s fountains as I returned again and again over the years to both places trying to make sense of the distance between the two.

Here is how I described that first levee drive in Water is For Fighting Over, the book that grew from the seeds planted on that April 20, 2010 drive:

Driving the Yuma County levee past Morelos Dam in 2010, I saw the last trickles of water from leaks in the dam and a shallow water table disappear within a few miles into a sandy, dry channel. This great river, the Colorado, around which I have spent much of my life, whose water I have showered with and drunk, which has grown the food I eat and floated my boats for hundreds of miles, simply disappears into the desert sand.

Storytelling as a vocation carries risk – the risk that a story often enough told becomes a substitute for the thing beneath it. Such is my story about Jennifer McCloskey’s map and my drive down the levee that spring morning. We hope that our bearing of witness is true to the thing, but it is always different than the thing. I wrote about this a year later in another context:

There’s an odd sort of detachment in the act of bearing witness for posterity instead of simply being in the moment. I know it professionally. I’m not a photographer, but I’ve been rethinking this because I’ve started taking pictures in my newspaper work recently. That fundamentally changes what has always been, for me, the act of bearing witness. Being at a “thing” when I’m working is different, the way I try to see more, remember and annotate and prepare for the retelling even as I’m experiencing. Instead of just being there and enjoying.

That trip to Yuma back in the spring of 2010 was my first attempt to learn the things I needed to bear witness to the Colorado River. I view this, still, as a work in progress.

From University of New Mexico Water Resources Program student Kirena Tsosie:

by Kirena Tsosie

It’s been increasingly difficult to maintain a “social distance” at our neighborhood park, so the afternoon walks have begun to range. I guess, adapting my friend Maria Lane’s hashtag, we could call it #geographybyfoot.

Headed north across the freeway last week, I found this in the flood control channel:

The Bird, AMAFCA channel east of Carlisle, Albuquerque NM

It appears to be either an early or hasty version of a beautiful piece of street art we’ve seen repeated around this part of Albuquerque. I did a post over at Better Burque with a map of the four we’ve found, including a gorgeous one along the railroad tracks north of downtown Albuquerque that has since been painted over.

We’re asking for BB readers to share any more that they find.

When I was writing Water is For Fighting Over five years ago, I built a little analytical model of Las Vegas water – projections of per capita demand and population growth, current patterns of water use and banking, risk to Colorado River water supply. At the time, the Southern Nevada Water Authority was aggressively pursuing construction of a pipeline to rural Nevada, to pump groundwater to augment the rapidly growing metro area’s supplies.

My model suggested to me that they didn’t really need the water.

I was timid in the way I wrote about it in the book:

The great failure in Las Vegas water management is an odd one. Like many cities, it has repeatedly underestimated its customers’ zeal for conservation, which results in overestimating how much water Las Vegas will need.

These failures are understandable. Water managers’ incentives favor erring on the side of caution. The consequences of having too little water are far greater than the consequences of having too much. So Las Vegas has continued to pursue expensive and politically costly plans to import more water into the Valley from rural Nevada, water that the Valley’s conservation success suggests may never be needed. (emphasis added)

Daniel Rothberg reporter yesterday that the Southern Nevada Water Authority has abandoned its pursuit of the pipeline:

The Southern Nevada Water Authority is ending a decades-long effort to build a controversial 300-mile pipeline to pump rural groundwater from eastern Nevada to Las Vegas.

On Thursday afternoon, the water authority confirmed in a statement that it would not appeal a recent court ruling that denied the agency a portion of its water rights.

The decision means the water agency is shelving a development project that has long inflamed tensions between rural and urban Nevada, from the Legislature to the courts, and eclipsed nearly all other water issues in the state.

This is one of the most striking examples to date of the argument I’ve been making ever since I had the epiphanies that drove my work a half decade ago on Water is For Fighting Over – municipal water demand is declining as fast as, or faster than, population growth, opening up enormous opportunities in our pursuit of sustainable water management in the West.

In the time of pandemic, I’ve been thinking a lot about small rural community water systems. This is in part because of work one of our University of New Mexico graduate students was doing in the Time Before, which seems super relevant now. Tucker Colvin just defended his thesis in UNM’s Geography and Environmental Studies program (I was on his committee, it was one of our university’s first Zoom defenses of the new era).

Tucker, working with UNM Water Resources Program student Amy Jones and Geography faculty member Ben Warner, spent oodles of time interviewing rural New Mexico water system managers to better understand the challenges they face. It was fascinating to me, as someone who’s spent most of his time talking to big municipal and ag system operators, a window into a world I’ve not thought enough about.

UNM’s Graduate Studies folks did a nice writeup on Tucker and his work:

By interviewing managers of drinking water systems, he discovered “that water systems face numerous issues including deteriorating infrastructure, limited funding, overly burdensome regulation, and perhaps most importantly, not having enough engaged people to manage their water systems.” Additionally, Tucker explains, “The state is also promoting regionalization as a blanket policy to promote sustainability of water systems. This research finds that this can be a useful tool in some cases, but for many communities it is perceived as taking away local control of a vital community resource and giving responsibility to a distant entity. This process can resurface historical political tensions and interactions between communities and government agencies. Many communities are in fact already organically and informally cooperating and sharing resources with their neighboring communities. Some policies and institutional structures created by the state seem to be innocuous and were likely created with good intent, but they are sometimes reinforcing power structures and keeping underserved communities marginalized.”

Once we come out the other side of our current predicament, I look forward to helping Tucker in his goal to share his findings with folks who can help move his insights into the policy world.

railroad track graffiti, Albuquerque’s North Valley off Vineyard

My current favorite word is “hooligan”.

It’s origins are murky, but the authors of the Oxford English Dictionary say it first appeared in newspaper stories in 1898, to whit:

1898 Daily News 8 Aug. 9/3 The constable said the prisoner belonged to a gang of young roughs, calling themselves ‘Hooligans’.

The story behind its emergence is unclear. Again, per OED:

The word first appears in print in daily newspaper police – court reports in the summer of 1898. Several accounts of the rise of the word, purporting to be based on first-hand evidence, attribute it to a misunderstanding or perversion of Hooley or Hooley’s gang, but no positive confirmation of this has been discovered. The name Hooligan figured in a music-hall song of the eighteen-nineties, which described the doings of a rowdy Irish family, and a comic Irish character of the name appeared in a series of adventures in Funny Folks.

And so, from the beginning, it has carried a combined sense of thuggishness and rowdy comedy.

In the Time Before, my friend Scot and I had begun exploring combination train/bike expeditions for our weekly Sunday ride. Several involved meeting up at the Albuquerque depot and taking the train north, being deposited at various places up the Rio Grande Valley for a long ride home. As such, the train took us through the raggedy light industrialness of Albuquerque’s North Valley. The tracks are lined with the most remarkable graffiti, and every train trip through, I was reminded that I needed to find a way back in, to enjoy the space at leisure.

Train tracks are like alleys, corridors through a city largely forgotten except to their denizens. It’s where I find the best graffiti. But unless you’re on the train, they are largely impenetrable, fenced off save the intermittent street crossing. Impenetrable, that is, to all except the hooligans.

I was riding last week across the North Valley, trying find a new way to cross the tracks when I turned, not quite randomly, on a street called “Vineyard.” (I’ve been working with a couple of UNM Water Resources graduate students piecing together the history, nature, and structure of agriculture in the region, so Vineyard Road has been of interest for a while. In pieces, I’ve ridden the length of it. There are no vineyards remaining. This is what we mean by “#geographybybike”.)

Vineyard Road had the usual “No Outlet” sign. On the bike, I’ve learned to ignore them. Where cars cannot go, pedestrians often find their way. In this regard, Vineyard did not disappoint.

Where the street stubbed into the railroad tracks, the fence was cut, admitting me to the rich alleyworld of the railroad tracks. The hooligans, once again, did not disappoint.

the hooligans did not disappoint

Rio Grande Oxbow, 2020-04-09, by John Fleck

I was talking last week with one of my collaborators about the challenge of working. All the things that so fully occupied my time and brain seem so inconsequential right now.

I envy friends filling the quiet with productive work.

Me? I ride my bike.

In the Time Before (was it just two months ago?) my UNM friend and colleague Becky Bixby and I delightedly tromped around Albuquerque’s Rio Grande with Mary Harner, a faculty member at the University of Nebraska who’s leading a fabulously eclectic study of the Rio Grande and some other rivers.

I first met Mary 15 or 20 years ago, when she was a PhD student at the University of New Mexico doing Rio Grande bosque ecology. She’d done some neat work back then using repeat aerial imagery to look at how the river system had changed. The new work is in some sense a return to that.

Mary and her Nebraska collaborator Emma Brinley Buckley have been in and out of Albuquerque for several years studying our Rio Grande with fresh eyes. Combining science with digital storytelling, they’ve been trying to make sense of the changes our river has undergone over the last century.

On their last few visits, they’ve been zeroing in on the stretch of river through the heart of Albuquerque, collecting old aerial maps and photographs. Emma’s done some nice repeat photography (see example here), and we spent a fruitful day in January poring over orthorectified aerial images over time.

the Rio Grande “oxbow”

One in particular drew our attention – an area along the west side of the river for which Mary and her colleagues had found two images taken in 1959, one in the early spring and one in fall. It included a place we call “the oxbow” – an old cutoff meander at the base of a long, steep bluff along the river’s western margin.

In Life on the Mississippi, one of my pandemic reading diversions, Mark Twain offered a marvelous explanation of how such cutoffs form when a river decides to straighten out a sinuous bend – “the water cleaves the banks away like a knife”.

“There is something fascinating about science,” Twain wrote. “One gets such wholesome returns of conjecture out of such a trifling investment of fact.” So have Mary, Becky, and I been reaping returns on the facts of Mary’s aerial photos. In 1959 it seems not to have been a river straightening a sinuous bend, but rather humans directing heavy equipment to straighten the Rio Grande here, to more efficiently deliver water downstream during drought. You can see the cutoff happen in the before and after 1959 pictures.

Those of us who work and play on and around Albuquerque’s Rio Grande have long wrestled with this central fact – a river that once meandered a flood plain, straightened and channelized in the 1950s, turning it from river into water delivery ditch. Mary’s aerial photos electrified me when I first saw them, a snapshot in time capturing that central fact.

If you look closely at my picture at the top of the post, you can see a line of “jetty jacks”, metal structures installed that summer of 1959 to help stabilize the river’s flood plain. They show up in the second of Mary’s 1959 images, and they remain today. The oxbow itself also remains, the only sizable swampy bit along this stretch of river.

Neighborhoods have encroached on the bluff above it, save one piece of protected city open space park and one undeveloped parcel that is the subject of intense politics right now. Well, which was the subject of intense politics in the Time Before. Hard to know what new home development looks like in the Time After, if there is such a thing.

As I said at the outset, I’ve not been able to focus on the deep work that used to so fill my mind. We’re keeping the UNM Water Resources Program’s trains running, and I’m struggling mightily to figure out how to teach students who I can talk to face to face. But that’s about all the brain share I have right now.

So I ride my bike, to the bluff above the oxbow, and take pictures for Mary and Emma, who can’t be here.

Cabezon Peak, a bike, and a Bud Light can. Photo by Kevin Carns

My friend and former student Kevin Carns is a truly gifted Bud Light can photographer. Cabezon Peak, the bike, the can – a compositional masterpiece.

Some years ago when we were out riding, my friend Scot pointed out that the empties we saw a long the roadside were almost invariably Bud Lights. So we began documenting them. The resulting Twitter photo essay is but a sampling. If we stopped to photograph every single one, we’d rarely get past the first few miles of a ride.

While it has been suggested that it would be a service to pick them up after photographing, that would conflict with the prime directive of Bud Light can photography – do not touch the Bud Light can. Plus how would I carry them? I’m on a bike!

Over time, friends have begun sharing their own Bud Light cans, which I’ve happily added to the growing Twitter thread. We’ve seen them from as far away as Jeff Kightlinger’s entry from Oxford, Mississippi.

Cabezon Peak is a landmark here, an old volcanic neck out along the Rio Puerco west of Albuquerque, so largely statuesque that you can see if from many miles away if the angle’s right. Kevin seemed surprised when I suggested the above was my favorite of the genre – “any semblance of masterpiece is by pure accident, it was the end of a long ride and I snapped a quick pic.”

The humility of a truly gifted Bud Light can photographer.

water flowing at Laguna Grande, March 2 2020

UNM Water Resources Program student Annalise Porter tipped me off to this, from Audubon’s Jennifer Pitt:

At a time when the world feels bleak and uncertain, I want to share a sign of hope: it has been raining, and the Colorado River is flowing in its delta #CORiver ?@RaiseRiver? pic.twitter.com/6W8iRcvm3r

— Jennifer Pitt (@JnPitt) April 2, 2020

Jennifer took the picture in early March at the Laguna Grande restoration site along the Colorado River in Mexico after a pouring rain. With a crazy wet March down there, water’s been flowing off of the normally arid landscape into the old river channel, which is dry mostly all the time. This isn’t a managed environmental flow release along the lines of what we saw in spring 2014 – it just rained!

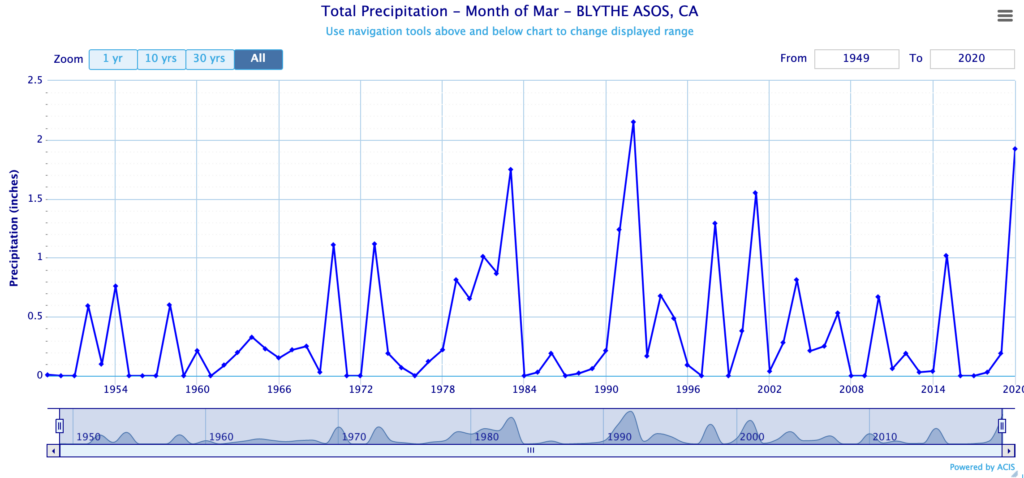

Working with University of New Mexico Water Resources Program students this spring modeling the Lower Colorado, we’ve been watching the impact of the wet weather north of the border. Blythe, for example, had its second wettest March in records going back 70 years – here’s an updated version of the graph we “discussed” in class this week:

Blythe’s wet March 2020

As a result the Palo Verde Irrigation District, for example only diverted 38,000 acre feet of water from the Colorado in March, a bit more than half of what it took in March a year ago. Imperial Irrigation District’s March diversions this year were about two-thirds of what it took last year.

Buried in the Bureau of Reclamation data on flows in this stretch of the river is a remarkable amount of runoff from wetted lands into the river, which is what Jennifer said is happening in Mexico. When it rains, ag water demand goes down, environmental flows go up. As Jennifer said, in the midst of the bleak and uncertain, this is a nice thing to see.