Keeping eyes on process

Allen Best gives us a good first pass in his niche (the Big Pivot) on the on-the-ground impact of the attempted freeze on Inflation Reduction Act funds on rural electricity in Colorado:

Electrical cooperatives in Colorado have been promised well more than a billion dollars in federal aid through the New ERA program.

The carve-out in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 was intended to help electrical cooperatives, who mostly serve rural America, make the energy transition from coal to less-polluting sources. Colorado-based Tri-State Generation and Transmission lobbied hard for the New ERA (Empowering Rural America) funding and will be a major beneficiary. It is in line to get $670 million.

Will the money eventually arrive? Donald Trump in his first days as president ordered a freeze on distribution of funds.

There’s a lot of noise right now, some of it intentionally sown chaos to distract, some of it intentionally created chaos to cause substantive change, and some of it gross incompetence. It’s difficult to tell the three apart, but we need to keep our eyes on the substantive process. That’s what I need from my journalism right now.

Anne Castle steps down as the federal representative to the Upper Colorado River Commission

Worth sharing in full:

January 28, 2025

Re: Resignation as U.S. Commissioner to Upper Colorado River Commission

Dear (addressee redacted)

As requested, I am submitting my resignation as U.S. Commissioner and Chair of the Upper Colorado River Commission, effective January 27, 2025. I was honored to be

appointed by President Biden to this position and serving on the Commission has been a privilege. I am deeply appreciative of the opportunity to contribute to the vital work of managing and protecting the Colorado River.This is an existential time for the river. We are on the brink of putting in place an operating regime that will govern our lives and our economies for decades. We are currently trying to manage an immense river system with tools and structures that were not designed for the conditions we face today. The Law of the River has provided a

stable foundation for over 100 years, and we need to give it credit for the amazing development and thriving populations in the entire southwestern part of the country. But the law has not fully adapted to kind of hydrologic conditions we have seen in the past and expect in the future. Agreements negotiated in good faith decades ago are no

longer providing the intended balance of fairness.The operation of the Colorado River is a complex web. Pulling on one thread of the web vibrates through the entire system, with significant potential for unexpected and

adverse consequences. Sustainable operational solutions must be crafted by those who best understand and appreciate this complexity – the Colorado River Basin States and Tribes, the Bureau of Reclamation and other affected agencies and offices within the Department of the Interior, and the many dedicated stakeholders and professionals who rely on and care about the River.This type of process is slow, messy, cumbersome, and unscripted, but ultimately results in the best path forward. This is the course being followed now. Edicts imposed from outside the Basin, such as recent proclamations concerning California water, based on an inadequate understanding of the plumbing and motivated by political retaliation, upend carefully crafted compromises, create winners and losers, and unnecessarily spawn the potential to adversely affect the lives of millions of people as well as the ecosystems on which they depend.

During my time as the U.S. Commissioner on the UCRC, I have had the opportunity to witness an evolution of role of the 30 Basin Tribes in Colorado River management. The commitment by the UCRC and its state commissioners to greater inclusion of Tribes in decision-making processes and more robust consideration of Tribal interests and issues has been extraordinary and had tangible results. The Memorandum of Understanding between the UCRC and the Upper Basin Tribes cementing adopted processes of cross communication and committing to shared goals is an historic first in the Basin. I am optimistic that, despite the rescission of the Executive Order on environmental justice, progress toward more meaningful participation by Tribes in Colorado River decision-making will continue.

In this position, and in my former role as the Assistant Secretary for Water and Science at the Department of the Interior, I have had the privilege to work with many dedicated and professional public servants within the Department and particularly in the Bureau of Reclamation. Despite being vilified by the very Administration they serve, these federal employees continue to strive to fulfill the mission of their agencies. The abrupt imposition of disruptive new terms of employment and undermining of civil service entitlements and expectations are explicitly designed to result in a wave of resignations, which are unabashedly welcomed by the architects of such policies. This broad brush, unfocused purge in furtherance of the stated goal of liberating large corporations from regulation they do not care for will result in attrition of expertise, damage to the American public, and specifically, a more disordered and chaotic Colorado River system.

I wish only the best for the Upper Colorado River Commission and its Commissioners. Both the staff and the Commissioners are dedicated and hardworking and fully

committed to their responsibilities. I will be cheering their efforts to reach a negotiated operational compromise that will sustain the River in the decades to come.Sincerely,

Anne J Castle

AI as physical and social infrastructure

Seen only as a collection of concrete and light poles, a highway is not racist. But the highway is a system within a system, and its path through a city or town can trace the boundaries set by prejudice. These paths are carved into cities based on decisions that prioritize categories of people through a lens of economic value. Once completed, highways may have been inaccessible to the lower-income communities they had segregated.

Likewise, when biases based on gender, race, and other social traits are baked into LLMs, they perpetuate social and economic inaccessibility in ways indistinguishable from racism or sexism. The word choices predicted by a large language model are paths, too, and are directed by probabilities. Whatever progress has been made in minimizing the bias of these models has been contingent on pressure from policymakers and regulations to ensure it was a priority.

Space graffiti

Space Graffiti. Photo by John Fleck, January 2025

And out of the ground the lord God formed every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air; and brought them unto Adam to see what he would call them: and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof.

– Genesis 2-19 (King James)

When I was a youngster experimenting with being a writer, I worked on a short story (never finished it, I was never very good at making stuff up) about naming things. The character was socially awkward, lived in a scrabbly desert town on the outskirts of L.A., settled like drift on the edge of an arroyo left behind by the summer rains. He lived in a trailer and spent his time learning the names of birds.

For Sunday’s bike ride we walked, or maybe hiked is the right word, across the marvelously dystopian frisbee golf course (disc golf course?) along Tijeras Arroyo on Albuquerque’s south side. The Brent Baca Memorial Disc Golf Course is stripped of the manicured aesthetic of golf golf (the kind with clubs and balls) – the Baca has graffiti and skulls on the top of poles and such.

For Sunday’s bike ride we walked, or maybe hiked is the right word, across the marvelously dystopian frisbee golf course (disc golf course?) along Tijeras Arroyo on Albuquerque’s south side. The Brent Baca Memorial Disc Golf Course is stripped of the manicured aesthetic of golf golf (the kind with clubs and balls) – the Baca has graffiti and skulls on the top of poles and such.

This stretch of Tijeras Arroyo is an urban castoff. Back in the 1930s, the old maps show a road running south of town, across the undeveloped mesa to Hicks Dairy, which advertised tuberculosis-free cows. A combination of a World War, a Cold War, and the growth of air travel covered the mesa with an airfield and a lot of barbed wire, and Tijeras Arroyo became a stranded leftover scrap of urban fabric barely accessible via a circuitous road named after Albuquerque’s most famous boxer. There was a jail there for a while (notably site of the vaguely infamous “Slippery 7 Escape” on New Year’s day, 1970), and some sewage sludge. Today there’s a shooting range and the “Montessa Park Convenience Center,” which is a particularly inconvenient place to haul a trailer full of trash.

It would be ridiculous to try to explain why we were out there on a freezing January Sunday morning, other than that it seemed too cold to ride and “hiking” presented itself as a better option.

A young friend hipped me to the idea of “urban exploring” as a thing with a name, and as I mentioned above, I have long been entranced with the power God gave us (my atheism notwithstanding) to name things. One of the premises of our urban exploring is that no place is uninteresting, but in the hierarchy of interesting, the raggedy bits are the best – alleys and flood control channels, the circumnavigation of junkyards, the perimeter fences of the military industrial complex. Places of graffiti.

Tijeras Arroyo is delightfully raggedy.

In preparing for Sunday’s outing, I had occasion to spot this in the satellite map imagery:

Space graffiti, as seen from space.

The artists’ canvas here is the sloped plastic sides of an old sewage lagoon, about the size of a football field (take your pick of footballs, this isn’t science). It’s maybe from the old jail, or a relic of the city sewage sludge disposal operation.

On Language

Conversation with my (h/b)iking buddy landed on Roland Barthes “The Death of the Author,” about the role of the intention of the author in literary criticism. We’re not as highbrow as it sounds, but the point of these outings in part is to make sense of the world by being in it and talking about it, and I’ve been entranced lately with the gap between graffiti’s meaning and intention, and how I as an enthusiastic audience member take it in.

No right answers here. My (h/b)inking interlocutor made patiently clear that I was over-interpreting Barthes’ intent, which is kinda meta. I can see a rocket ship and a pretty enthusiastic cross in the space graffiti, but now I’m afraid to even consider whether I’m supposed to be trying to tease out the artists’ intent or just take in the piece, bringing my “urban explorer” mindset to the experience.

It was way too cold to have biked, but at the pace of walking under a winter sun it was lovely.

The January 2025 24-month study is a major caution sign for the Colorado River Basin

The Tripwire

By Eric Kuhn, John Fleck, and Jack Schmidt

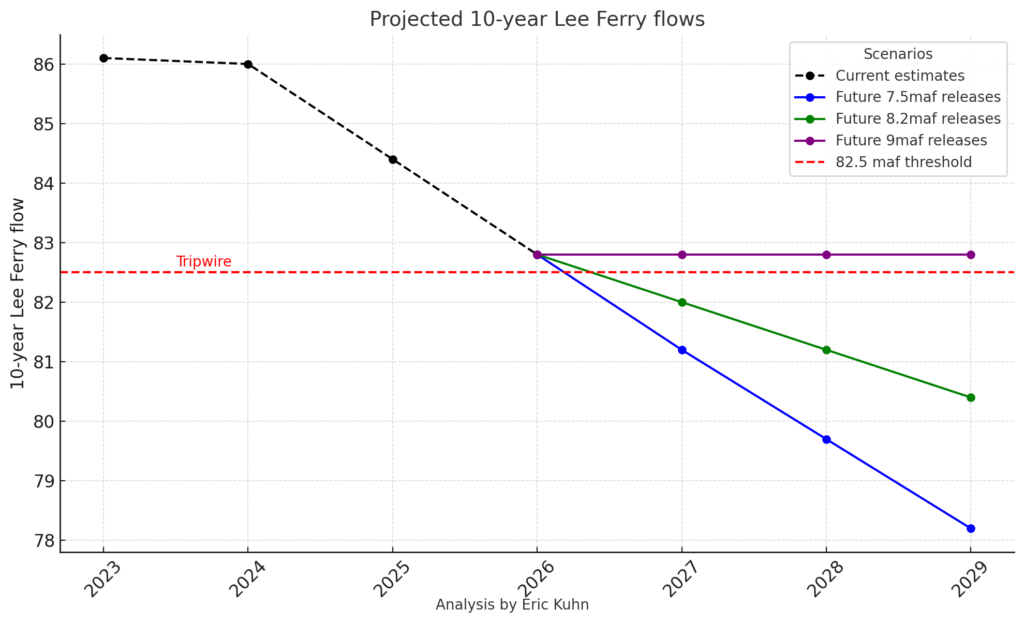

On January 16th, the Bureau of Reclamation released the January 2025 24-Month Study. Based on the January 1st runoff forecast into Lake Powell, the projected “most probable” annual release from Glen Canyon Dam for Water Year 2026 is now 7.48 maf. This needs to be taken as a significant caution sign because it shows that we are on a clear trajectory to hit what Colorado’s Jim Lochhead first called the 1922 Compact’s first “tripwire” (82.5 maf/10-year) as early as 2027. Given the current stalemate between the Upper and Lower Division States over how the reservoir system should be operated, it means the potential for basin-wide litigation is now in the “Red Zone.”

The January 24-Month study is the first in each water year to be based on a published forecast from the Colorado Basin River Forecast Center’s runoff model – the first to be based on actual snowpack. The January 1st runoff forecast for unregulated April-July inflow to Lake Powell was 5.15 maf (about 81% of average). This results in a projected 12/31/2025 elevation of Lake Powell of less than 3575’ making the annual release for Water Year 2026 7.48 maf. Of course, the forecast will change as the winter progresses. In fact, the January mid-month forecast dropped by 300,000 acre-feet to 4.85 maf. At this point in the winter our confidence in the “most probable” forecast is low and in recent years, the track record has been to overstate future runoff suggesting that the we should pay equal attention to the “minimum probable” forecast. (See Wang et al, Evaluating the Accuracy of Reclamation’s 24-Month Study Lake Powell Projections.) Also remember that the actual decision on the WY 2026 release is not made until the Spring runoff is over and the August 24-Month study is released.

Lee/Lee’s/Lees Ferry on the Colorado River. Photo by John Fleck

A 7.48 maf release from Glen Canyon Dam bodes trouble for the basin because it takes us very close to the tripwire. Simply put, the tripwire is the ten-year flow at Lee Ferry at which the Lower Division States can claim the Upper Division States are in violation of the 1922 Compact. Under the compact, the Upper Division States have two specific flow obligations at Lee Ferry: (1) to not cause the ten-year flow to be depleted below 75 maf every ten consecutive years, and (2) to deliver one half of the annual delivery to Mexico under the 1944 Treaty if the “surplus” is not sufficient. If there is no surplus and the delivery to Mexico is 1.5 maf/year, the Upper Division’s share is 750,000 af/year, resulting in a total ten-year delivery obligation of 82.5 maf. Since under Minute 323, Mexico shares in mainstem shortages, recent annual deliveries have been less than 1.5 maf. To keep the math simple, let’s call the current obligation (with no surplus) 82.0 maf. With a 7.48 maf release in WY 2026, the ten-year flow for 2017-2026 will be about 82.8 maf.

Keep in mind that the obligation of the Upper Division States to Mexico under the 1922 Compact has been a disputed issue since the Treaty was signed in 1944. The Lower Division believes there is no current surplus, thus the obligation is one half of the Treaty delivery. The Upper Division believes that since the Lower Basin is currently overusing its 1922 Compact apportionment, this overuse is surplus, and thus, must be delivered to Mexico. Following this thread, if the overuse is greater than 1.5 maf/year, the Upper Division would have no obligation to Mexico.

With an 82.8 maf ten-year flow at the end of Water Year 2026, the Upper Division States are still slightly above the tripwire with a cushion of about 800,000 af. The problem is what happens in the next one to three years. From 2015-2019 annual the annual Glen Canyon Dam releases were 9.0 maf/year. Note, the annual release from Glen Canyon Dam and the flow at Lee Ferry are not quite the same, the Paria River and leakage around the dam contribute another 100,000 -150,000 af/year to the flow at Lee Ferry (bonus flows). Because of the way the ten-year math works, at the end of WY 2027, the Lee Ferry flow for WY 2017 (~9.2 maf) will drop out and be replaced by the 2027 Lee Ferry flow, thus, to keep the ten-year flow greater than 82.0 maf, the 2027 flow will have to be at least 8.4 maf. AND, there are two more 9.0 maf releases in the pipeline, WYs2018 and 2019! That means that when those drop out of the sequence, the risk of the basin stumbling across the tripwire into litigation grows.

To stay above 82.0 maf, the total deliveries at Lee Ferry for the three-year period of 2027-2029, the annual release from Glen Canyon Dam will have to average about 8.8 maf/year (factoring in the bonus flows). Since 2012, the average unregulated inflow to Lake Powell is about 8.2 maf/year. After deducting 500,000 af/year of gross evaporation from the reservoir, the “net-of-evaporation” annual inflow is only about 7.7 maf/year. Going back to 2000, the net inflow is about 7.9 maf/year. Thus, to avoid going below the 82.0 maf tripwire, it will take either above average (post-2000) hydrology or continuing to draw down Lake Powell levels. If the hydrology is a bit drier than the post-2000 (or post-2012) levels, maintaining at least 82.0 maf/10-year may require drawing Lake Powell below minimum power. As Lake Powell levels approach minimum power, we approach environmental and power generation tripwires.

The fact that we’re on track for another year of below-average inflows to Lake Powell, another 7.48 maf/year annual release from Glen Canyon Dam, and on a trajectory to drop below a 1922 Compact tripwire adds another level of urgency for the basin states to break their current impasse over the how the system will be operated post-2026. The chances of Lee Ferry flows dropping below the 82 maf tripwire are high. The Colorado River Basin needs to be fully prepared before this occurs. With every 24-Month study, the basin’s litigation clock is getting closer and closer to that midnight hour.

Stable on the Colorado River: When “good” is not good enough

By John Fleck and Jack Schmidt

Stable isn’t good enough.

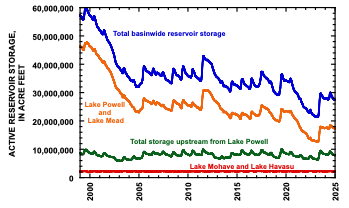

Preliminary year-end Colorado River numbers are stark. Total basin-wide storage for the last two years has stabilized, oscillating between 30 and 27 maf (million acre-feet), where storage sits at the start of 2025[1]. That is lower than any sustained period since the River’s reservoirs were built (Fig. 1). Stable is better than declining, but we did not succeed in rebuilding reservoir storage during 2024’s excellent snowpack but modest inflow. Although reservoir storage significantly increased after the gangbuster 2023 snowmelt year, we have not protected the storage gained in 2024 when inflow to Lake Powell was ~85% of normal from a 130% of normal snowpack. We can’t rely on frequent repeats of 2023; we must do better at increasing storage in modest inflow years like 2024.

Why is this happening?

Less water.

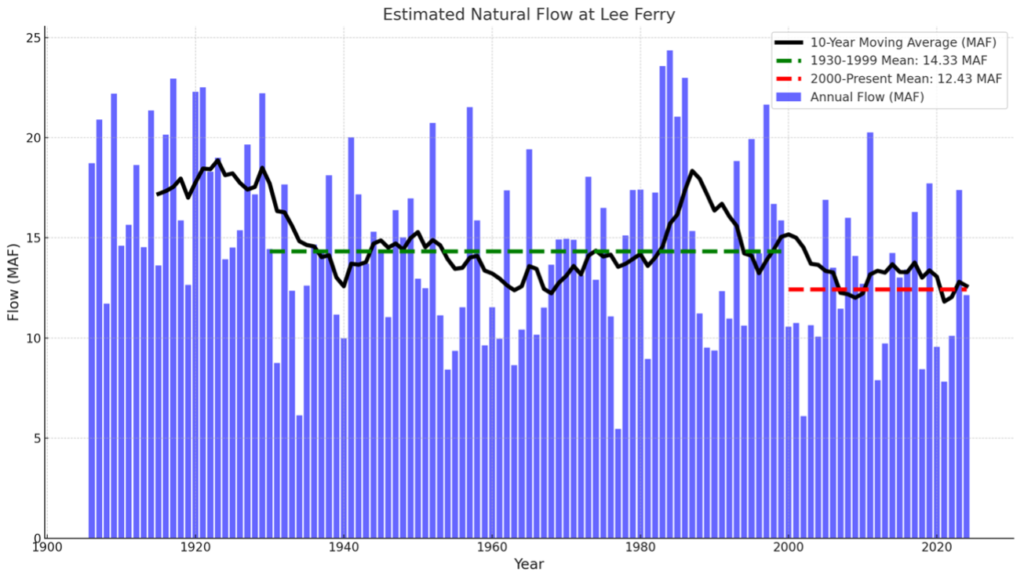

The phrase “the new normal” can be misleading, suggesting a new, more stable state for the climate. It’s not gonna be stable. But by one reasonable measure – total estimated natural flow in the Colorado River at Lees Ferry – Calendar Year 2024 was typical of the first quarter of the 21st century, with a preliminary estimate of 12.1 million acre-feet “natural flow.” Thus, the calendar year average annual natural flow at Lees Ferry between 2000 and 2024 has been 12.4 maf/yr, down from 14.3 maf for the period 1930-1999. An additional 770,000 af/yr in side inflows between Lees Ferry and Lake Mead add to the available water supply[2].

That we made the cuts needed to stabilize reservoir levels with a natural flow at Lees Ferry as low as 12.1maf would have been a substantial achievement in the wetter “before times.” Now, it’s table stakes. The most important point is that we absolutely did not rebuild storage in 2024, despite a 130 percent snowpack. We must do better in reducing total basin consumptive use.

Once again in 2024, we saw substantial water use reductions among the states of the Lower Colorado River Basin. Total U.S. Lower Basin main stem use of 6.08 maf is the lowest since 1985 (meaning the lowest since the Central Arizona Project came on line). California’s use, based on preliminary numbers published by Reclamation seems to be the lowest since 1950, and use by the Imperial Irrigation District seems to be the absolute lowest in a dataset that goes back to 1941. These are important achievements, to be celebrated.

With regard to the other two major U.S. areas of use – Lower Basin tributaries and the Upper Basin as a whole – we have no idea what 2024 consumptive use was. This is a problem. Lower Basin main stem use is quantified through Reclamation’s annual accounting reports and reported on a nearly daily basis during the course of the water year. River flows and reservoir levels across the basin are similarly reported in public, transparent ways. That’s how we’re able to provide the data you see above. Anyone can download and crunch the numbers. The general public can’t readily do that for consumptive use in the Upper Basin or Lower Basin tributaries.

As Elinor Ostrom noted in her classic book Governing the Commons, shared understanding of the resource is crucial to successful water management. Increasingly, areas of uncertainty have become contested ground, as the genuine technical uncertainties collide with the motivated reasoning of political actors across the basin.

With respect to the Upper Basin, we note that the rhetoric that Upper Basin water users suffer shortages in dry years has shifted to a broader claim that Upper Basin users always suffer shortages. We quote here from the Upper Basin states’ January 2 press release: “There are acute hydrologic shortages in the Upper Basin every year – there simply isn’t enough water in any year to satisfy current needs in the Upper Basin every year. The Upper Basin has made uncompensated cuts to their water users every year for the past 24 years.” Some of the data to support this assertion was presented at the December 2024 UCRC meeting, and we look forward to a more complete and transparent accounting of these data, because these data are crucial to a robust Colorado River management discussion. The Upper Basin’s experience of “acute hydrologic shortages … every year” is exactly what John Wesley Powell described in 1878 in the first edition of The Arid Lands Report. Nothing has changed, and the challenge of agriculture throughout the watershed has been well known for 150 years. We also note that consumptive use data throughout the basin has not been integrated with the important findings of Richter et al (2024) who documented the proportion of water used by different agricultural sectors. They estimated that 55% of all Colorado River water use supplies livestock feed.

We leave a discussion of Lower Basin tributary use for another post but note that in both the cases of the Upper Basin use and Lower Basin tributary use, the numbers are entangled in the current Upper Basin-Lower Basin feud, which makes serious efforts to think about how to manage water at the Basin scale, rather than simply defending parochial interests, much more difficult. It is important that the general public not employed by a state or water agency, and therefore not beholden to local parochial interests, help the basin community as a whole navigate these technical issues.

Conclusion

The stable reservoir levels at the end of 2024, despite another year of deep Lower Basin water use reductions, should be cause for alarm. Deeper cuts are needed. But without a shared understanding of water use elsewhere in the basin, we’re flying blind.

[1] Basin-wide reservoir storage reached a peak of 29.7 maf on 13 July 2023 and was subsequently drawn down to 27.5 maf by mid-April 2024. Inflow from 2024 snowmelt rebounded basin-wide storage to 30.0 maf on 6 July 2024, and storage was subsequently drawn down to 27.4 maf by 31 December 2024. Retention of storage in Lake Mead and Lake Powell has been somewhat better during the same period. Combined storage in Lake Mead and Lake Powell peaked in mid-July 2023 at 18.0 maf, declined to 17.1 maf by mid-May 2024, increased to 18.5 maf on 8 July 2024, and was 17.3 maf on 31 December 2024. Thus, storage in the two largest reservoirs at year’s end was slightly greater than it was at its spring 2024 minimum just before storage increased when significant snowmelt reached Lake Powell.

[2] This estimate is calculated as the difference between annual flow measured just upstream from Diamond Creek in western Grand Canyon and measured at Lees Ferry.

Water for Navajo is the latest victim of Colorado River Basin governance dysfunction

A dry place. Photo by John Fleck

Winters rights are no match for the current dysfunction of Colorado River Basin governance.

Shannon Mullane at the Colorado Sun has been on this, and last week had some useful details:

Advocates of a deal to secure reliable water for thousands of tribal members in Arizona raced to win Congressional approval until the final hours of the session in December.

They didn’t make it.

“We just ran out of time to address all the issues,” said Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources and principal negotiator for the state on Colorado River matters.

Part of the catch is the cost. This is a really expensive settlement, though it’s reasonable to point out all the other expensive water projects built over the last century with massive taxpayer subsidy to provide water to non-Indian communities. But, as Mullane (thanks, Shannon!) reported back in December, one of the main hitches is the way the deal is entangled in broader Colorado River Basin uncertainties about who can move what water where:

State officials have asked for clarity on how water will move across state lines. And Colorado River officials in Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming have concerns about how the settlement would allow water from their basin to be used farther downstream.

Finger-pointing for the failure to work out an agreement is appropriate, but ultimately doesn’t matter. The bottom line here is that the failure of the Colorado River governance community as a whole to work out these details means some of the most water-poor communities in the nation continue to not have water, while the people blocking the agreement do have water.

Let me say that twice, for emphasis: Communities that do have water are blocking access to water for their neighbors who don’t have water.

That’s not OK.

A functional Colorado River governance community would have been able to solve this. Its failure, rooted in parochial attempts by communities to protect their own water supply, is a concrete demonstration of how hollow talk about Tribal inclusion really is.

Do better.

Dying embers

Matt Pearce, formerly of the LA Times, shares the sadness I feel about the calling to which I devoted so much of my life:

One of the odd experiences of this week’s local disaster for me was that it was my first in years where I wasn’t working in a newsroom, a privileged position where information from your colleagues pummels you in the face through nonpublic channels like Slack. This time, I’m a civilian. And this time, the user experience of getting information about a disaster unfolding around me was dogshit.

Lousy Rio Grande snowpack, but the runoff forecast is not as bad as I thought!

The January NRCS Rio Grande runoff forecast is lousy: a mid-point forecast of 65 percent of average at Otowi (upstream of Albuquerque) and 37 percent of average at San Marcial (downstream of Albuquerque). Based on the current snowpack, I expected worse. Forecaster Karl Wetlaufer, in the email distributing the numbers, explains:

After a wet start to the water year conditions have become drier as of late in the Rio Grande basin. In general January forecasts are for below normal volumes across much of the basin with the exception of some headwaters points in Colorado. This temporal pattern of moisture accumulation has also led to a large discrepancy between water year precipitation and snowpack, as much of the precipitation for the water year was received before the primary snowpack began to accumulate. Forecast models utilize both precipitation and snowpack for forecast values may be higher than you would anticipate in looking at snowpack alone. Particularly in much of New Mexico. It is worth bearing in mind that early season precipitation adds to the soil moisture which can in turn aid in springtime runoff efficiency.

Wetlaufer also reminds us that there’s a lot of snowpack season ahead of us. The numbers above are the median forecast. The one-in-ten wettest side (10 percent exceedence) is ~115% of average at Otowi, and the one-in-ten dry (90 percent exceedence) is less than 20% of average.