By Eric Kuhn

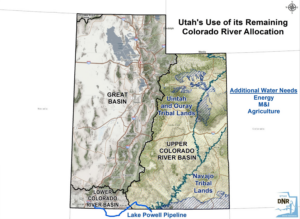

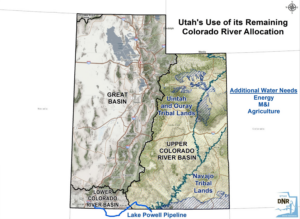

The Lake Powell Pipeline, moving Upper Colorado River Basin water to the Lower Basin

As the Colorado River Basin’s managers wrestle with thorny questions around the proposed Lake Powell Pipeline, a colleague who works for a Lower Colorado River Basin water agency recently asked a question that goes to the heart of the future of river management: With land in the Lower Colorado River Basin, why doesn’t Utah have a Lower Basin allocation?

The answer, arising from deep in the history of the Law of the River, goes far beyond the possible use of some of Utah’s Upper Basin water in the Lower Colorado River Basin’s Virgin River Valley. It strikes at the heart of important and as yet unresolved questions in the river’s future – about accounting for reservoir evaporation, and who bears the responsibility for, and benefits from, water flowing down the Lower Basin’s tributaries.

The lack of a “Lower Basin Compact”

The simple answer to my colleague’s question is that Utah has no apportionment of Lower Basin water because there is no Lower Colorado River Basin Compact.

The negotiators of the 1922 Colorado River Compact allocated water to the Upper and Lower Colorado River Basins with the clear intention that the states of each basin would return to the negotiating table to work out the details of how their share of the water would be allocated and accounted for. The states with Upper Basin interests completed the task in 1948, negotiating the Upper Colorado River Basin Compact. Notably Arizona, which is not an “Upper Division State”, but which has land in the Upper Basin, participated, and was allocated a share of the Upper Basin’s apportionment.

In the 1920s and ’30s, there were many attempts, all unsuccessful, to negotiate a Lower Basin compact. They came close in 1927 when the basin governors met in Denver for the specific purpose of resolving the differences between Arizona and California. The Senate used the deliberations from 1927 as input to the mainstem apportionments to Arizona, California, and Nevada provided for in the 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act. But the language of the Act clearly suggests Congress expected a Lower Basin Compact to be negotiated to flesh out the details, much as later happened in the Upper Basin.

That never happened, though, and in the absence of a Compact, the present-day apportionments we all know so well – 4.4 million acre feet for California, 2.8maf for Arizona, and 300,000 acre feet for Nevada – are based on the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the intent of Congress when it debated and passed the Boulder Canyon Project Act in 1928. But in the absence of the a careful process of negotiation to cover the full range of issues that needed to be considered (as happened in the Upper Basin), the Supreme Court’s decision was narrow. It only covered under contracts between the federal government and water users downstream of Hoover Dam – not for water consumed on the Lower Basin tributaries or on the Lower Basin’s portion of the mainstem above Lake Mead.

In the 1930s, William Donovan came close

In 1930 President Hoover appointed Colonel William Donovan as special mediator to negotiate a Lower Basin compact. Donovan came close, but Arizona and California just could not make one final compromise. In both the 1927 and 1930 near misses Utah and New Mexico would have received from the 8.5 million acre-feet apportioned by the 1922 compact to the Lower Basin “all water necessary for use on areas of those States lying within the lower basin” – (see Science Be Dammed, chapter 8).

In 1952 when Arizona filed its Supreme Court case against California, one of its initial goals was a Court ruling that would be functionally equivalent to a Lower Basin compact. Among its claims for relief was that the court find that Arizona had the right to use all the one million acre-feet apportioned to the Lower Basin under Article III(b) subject only to the “rights of New Mexico on the Gila River and Utah on the Virgin River.” As the case proceeded, Arizona changed its tactics. It amended its original claims for relief arguing that the case was no longer about the compact. Instead, it was only about the intent of Congress to apportion water under the 1928 act. The Special Master and Supreme Court agreed and ruled that the Colorado River Compact need not be interpreted to decide the case. Since the court’s decision was limited to the water used in and below Lake Mead and avoided the compact, it falls well short of a Lower Basin compact.

Would we be better off with a Lower Basin Compact?

The entire basin would be much better off with a functioning Lower Basin compact. The problem is that to get there, the five states with Lower Basin interests – Arizona, California, and Nevada (the “states of the Lower Division”), plus Utah and New Mexico, which also have watersheds falling within the Lower Basin’s boundaries – would have to negotiate through several difficult issues that have never been resolved and for the moment are conveniently tucked away. These issues include dividing up the one million acre-feet of III(b) water, the “bonus water” provision added to the compact late in negotiations to sweeten the deal for Arizona. In addition to addressing the Lower Basin needs of Utah and New Mexico, Nevada also needs a piece of III(b) water to cover its uses on the Virgin and Muddy Rivers. Water from the dry-up of previously irrigated lands in these two drainages supplies the Southern Nevada Water Authority.

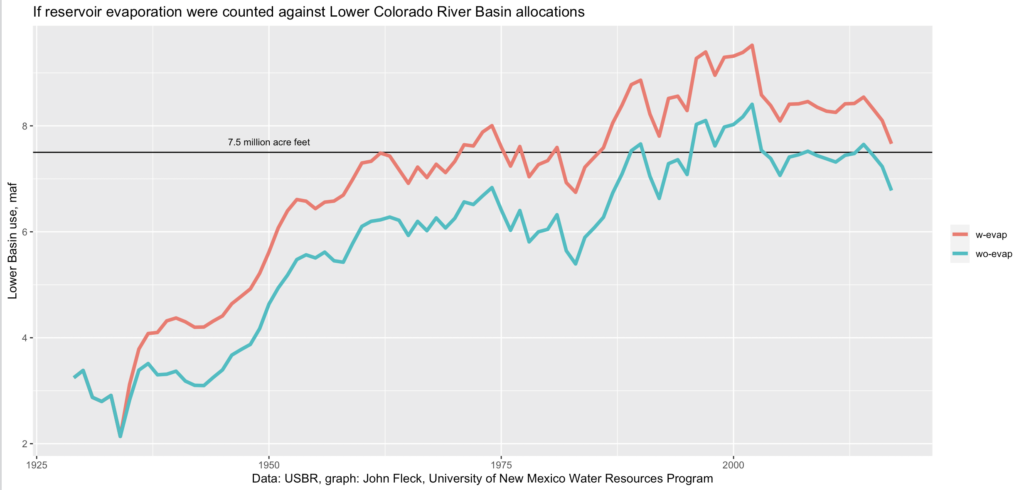

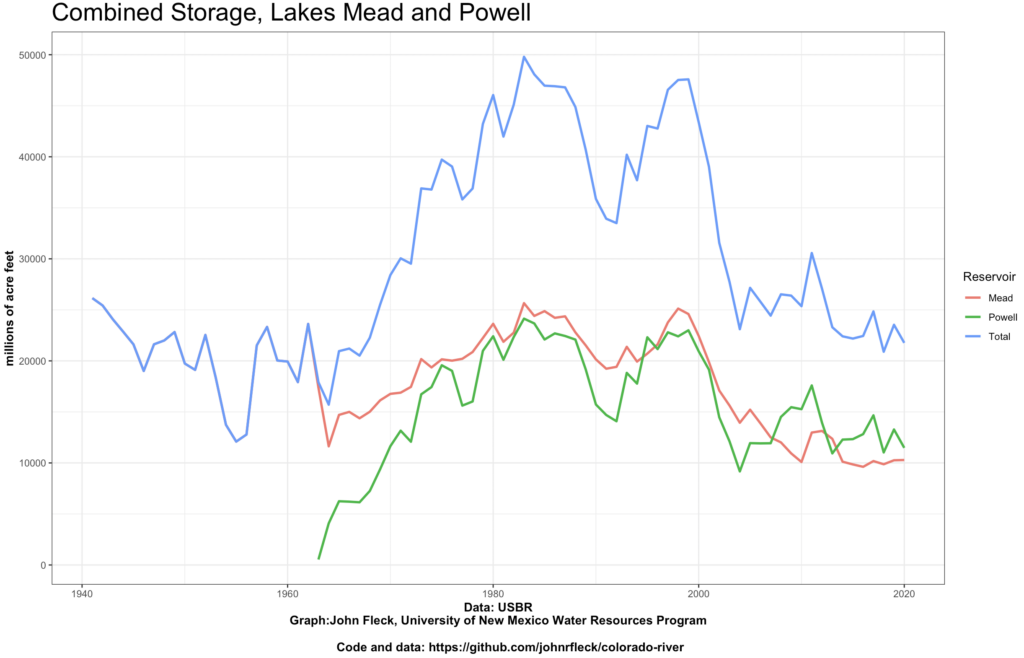

A second issue is dividing up the substantial evaporation use on the Lower Basin mainstem reservoirs. I have no doubt that the 1922 compact negotiators considered this evaporation a man-made beneficial consumptive use to be covered by the 8.5 million acre-feet apportioned to the Lower Basin, but it is not covered in the Supreme Court’s decision.

Third, there are difficult Lower Basin accounting issues to resolve, including how compact apportionments are to be measured. Yes, a century after the compact was signed, this fundamental issue has never been resolved (see Science Be Dammed, chapter 12). Another unresolved accounting question is how to address the depletion of groundwater hydrologically connected to the Colorado River.

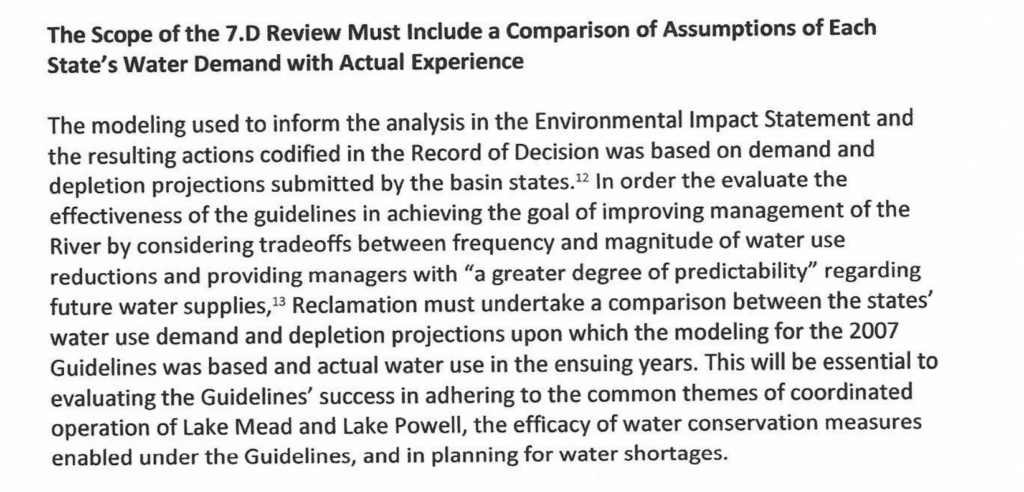

These accounting issues point to a bigger issue. The primary purpose of a Lower Basin compact would be to allocate among five states 8.5 million acre-feet of beneficial consumptive use – the amount apportioned to the Lower Basin by the 1922 compact. How would a compact address the reality that when tributary uses, reservoir evaporation, and hydrologically connected groundwater are considered, the Lower Basin is currently using more than 8.5 million acre-feet?

These major unresolved issues are why in Science Be Dammed John Fleck and I conclude that there is little incentive and major downsides for important playsers to a Lower Basin compact, thus it is unlikely to happen. The problem from my perspective as a former manager of an Upper Basin water agency is that through the 1948 Upper Basin compact, reservoir evaporation, hydrologically connected groundwater, and overuse are all addressed. Without a Lower Basin compact, important elements of the equity between the basins are missing.