On Apple Lane in Albuquerque’s Duranes neighborhood, City Well #4

Scot spotted it first, a pipe sticking up a few feet above the ground, a square locked box on top of it, behind a low fence on Apple Lane in Albuquerque’s Duranes neighborhood: City Well #4.

It was here on Jan. 31, 1957, that what we might think of as the first groundwater measurement of Albuquerque’s modern water management era was made. The depth to groundwater was 15.54 feet (measured, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, to the nearest hundredth of a foot). By early June, it had dropped more than 10 feet as the water supply wells in the surrounding Duranes field did their work to meet rising city water demands.

In a pandemic, masked Sunday bike rides with my friend Scot are one of the only human contacts left outside my immediate family and fucking Zoom calls, and after coming very close to pulling the plug on the rides, we set out this morning on a treasure hunt.

Here was the treasure:

Putting together some slides for a lecture last week, I’d noticed in the most recent report from Andre Ritchie and Amy Galanter of the USGS on Albuquerque groundwater monitoring a handful of wells with data going back to a single year – 1957. “What’s up with that?” I wondered.

A handy label confirmed that we had, in fact, found City Well #3. Southwest Corner, Los Poblanos Fields, Albuquerque

Four wells, helpfully labeled City Well #1, City Well #2, City Well #3, and City Well #4, were drilled that year across the floor of Albuquerque’s North Valley.

I’ve no doubt people were measuring groundwater here in some fashion before this time, but these four wells mark a turning point. One of the things I try to pay attention to, and encourage my students to pay attention to, is the question of why a particular piece of data is being collected. Data collection carries costs, and there’s intellectual profit in thinking about who collected it, and why. So I did some Googling, Scot helped with the old newspaper research (he has serious skills in that regard) and I stuffed a couple of folded sheets of paper into my pocket with maps giving the rough location of each of the wells.

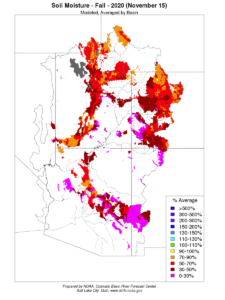

The mid-1950s were a critical time in Albuquerque’s water history. In the 1940s, the population of Bernalillo County (the greater Albuquerque area) had doubled, and in the 1950s, it nearly doubled again.

Newspaper stories from the period show a fear of running out of water, and trumpet the community’s success in drilling new wells. My favorite was a May 1954 headline bragging about pumping 38 million gallons in a single day – a record. “Despite the heavy use – which is perilously near the 40 million gallon daily capacity of the system – water officials said they received no complaints of low pressure,” the Albuquerque Tribune reported.

Soon, the Tribune reported, the new Duranes Well Field would add another 20 million gallon per day capacity, with a new reservoir and the ability to pump water up to the growing neighborhoods on the mesa to the east.

The tank you see in the background behind City Well #3 in the picture at the top of the post is the Duranes Reservoir, completed in 1954 to hold water pumped from the new field. As street name, Apple Lane, suggests, the field where it was built had once been an orchard. The old Duranes Acequia, one of the early irrigation ditches, still skirts the north end of the reservoir property.

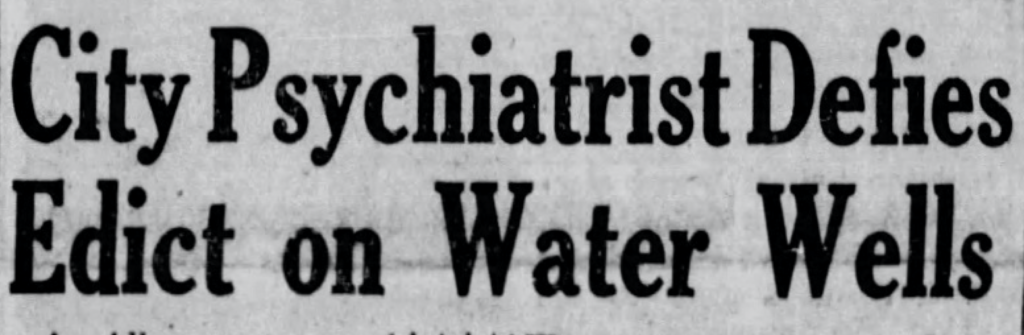

Not everyone was enthusiastic about all the new wells. In November 1956, the state’s top water regulator, Steve Reynolds, issued an order attempting to curb the city’s voracious groundwater pumping.

Since the 1930s, New Mexico had been a leader in recognizing the connection between groundwater and surface water – that when you pump from the ground, you end up depleting the flows of nearby rivers.

But to trigger the law, the state engineer had to issue an order, which is what Reynolds, cheeky bastard that he was, did in November 1956. Messy litigation ensued, with Albuquerque claiming that “as the successor to the Pueblo de Alburquerque y San Francisco Xavier, founded not later than 1706, it had the absolute right to the use of all waters, both ground and surface within its limits, for the use and benefit of its inhabitants”, to quote from the New Mexico Supreme Court’s 1962 decision in the case of Albuquerque v. Reynolds. Which Albuquerque lost.

We found all four of the 1957 wells – #3 at the southwest corner of Los Poblanos Fields, #2 where Sandia Rd. NW dead-ends into the railroad tracks, and #1 in the parking lot of Kasdorf Mfg., which makes “genuine walnut products for the awards and recognition industry”.

#2 was my favorite. What happened in the years after Albuquerque lost the lawsuit in 1962 is a story for another day, or maybe another book, but suffice to say that the water levels in #2 dropped for another 40-plus years before things finally turned around. Since 2008, it’s begun to rebound, rising 20 feet.

Sandia Rd. NW, where the well continues its service today, was one of the early streets in the area to turn over from the marginal farming once done there to suburban neighborhood. It sits today on the property line between a house and an apartment complex, a piece of Albuquerque history kept company by a trash bin, two old couches, and two discarded mattresses.

City Well #2, Sandia Rd. NW, Albuquerque, New Mexico