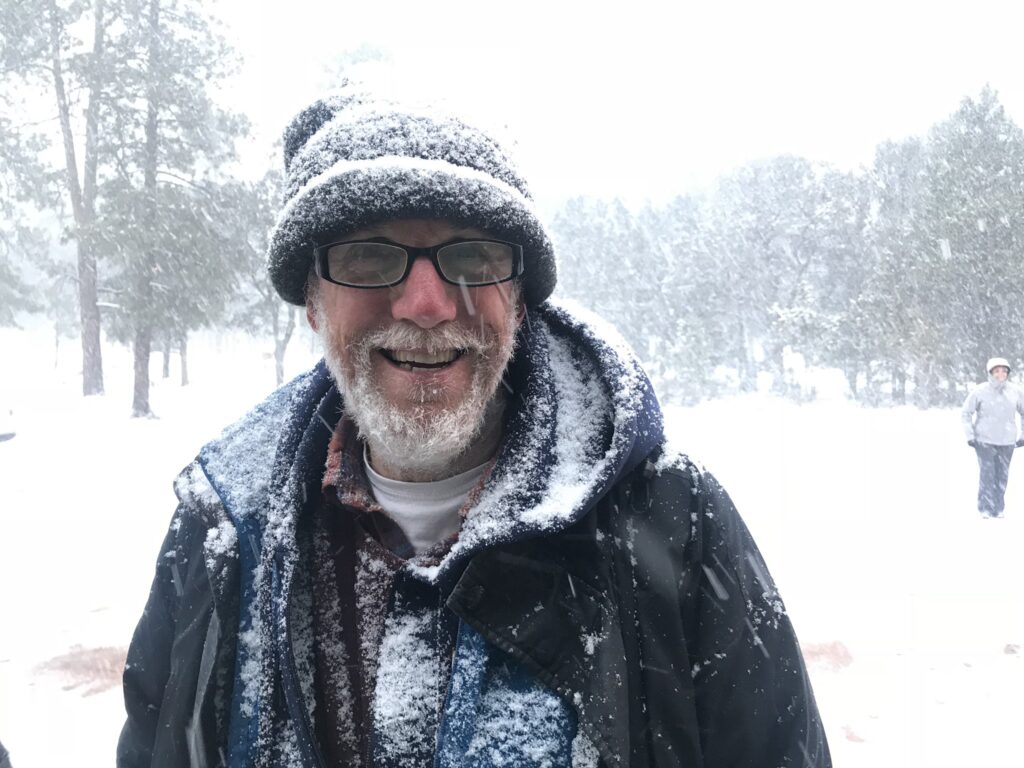

Tony Davis at the Grand Canyon, February 2018, courtesy Ry Rivard

On a Zoom call with a group of Colorado River brain trusters this morning, there was a realization that we’d all been talking in recent weeks to the same reporters.

Sometimes it’s someone new to the issues, looking for help with a single story. With dropping reservoirs, several pressing near-term political and policy questions, and a lousy runoff forecast, there’s a lot of that.

Often it’s one of the regulars – beat reporters who have been on this story for a while, who know its nuances well, and who offer their readers and listeners continuing coverage rather than a one-off.

In my journalism career, I did both kinds of work, but I always found far more value in the latter. It’s not simply that beat reporting allows the development and communication of more specialized expertise – although that’s important.

It’s that some kinds of stories demand repetition.

At its heart, the Colorado River story right now is pretty simple:

- The river was overallocated from the beginning.

- Climate change is making the problem worse.

- We have to figure out how to use less water.

Lather. Rinse. Repeat.

This is the antithesis of traditional newsroom culture’s definitions. “But we said that already,” the editor asks. “What’s new here?”

The value of repetition is a lesson I internalized from one of my Albuquerque Journal editors. I’d been writing about an environmental contamination issue here in Albuquerque, and at one point she said to me, “This is important, John. Find a way to keep it in the paper.”

We’d find some new “news peg” – a new set of sampling reports, a bureaucratic process step – and in the course of adding this new bit of information we’d also, by way of filling in the background, remind readers of all the old stuff. It was our way of saying, “Hey, look over here, this is important!”

This is why I loved Tony Davis’s story in the Arizona Daily Star over the weekend.

Less water for the Central Arizona Project — but not zero water.

Even more competition between farms and cities for dwindling Colorado River supplies than there is now.

More urgency to cut water use rather than wait for seven river basin states to approve new guidelines in 2025 for operating the river’s reservoirs.

That’s where Arizona and the Southwest are heading with water, say experts and environmental advocates following publication of a dire new academic study on the Colorado River’s future.

That fourth point is the news peg – “NEW STUDY SAYS“. And the study, by the Utah State Colorado River team, is great, a really important contribution to framing the issues we face going forward. But the three points before it are just versions of things Tony and the other Colorado River reporters have said before. Before. Before.

I think it’s accurate to say Tony has been writing about the Colorado River longer than anyone working today. I treasure my conversations with him – so smart about Colorado River issues, so smart about Arizona water issues, so smart about journalism issues. Every time I talk to him he’s already thinking two or three stories ahead. Tony’s a reporter’s reporter.

No one story solves the information problems of a busy audience being pulled in a million directions. It’s repetition that matters. “Oh wow, that Colorado River thing is in the paper again, it must be important!” Which is why the beat work by people like Tony is such an important service.

Lather. Rinse. Repeat.

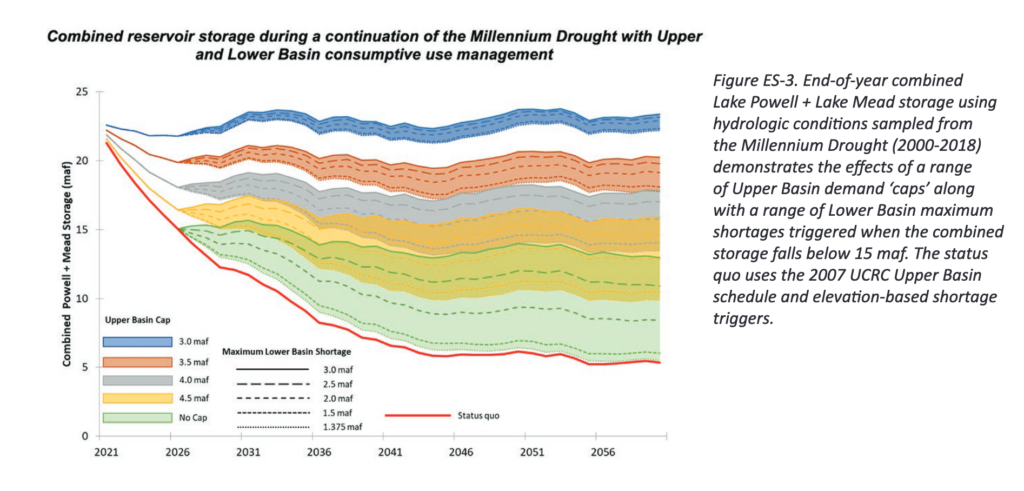

Stabilizing Colorado River reservoir levels under even moderate drought/climate change scenarios will require deeper water use reductions than basin managers have to date been willing to contemplate (at least publicly), according to a new analysis by researchers at the the

Stabilizing Colorado River reservoir levels under even moderate drought/climate change scenarios will require deeper water use reductions than basin managers have to date been willing to contemplate (at least publicly), according to a new analysis by researchers at the the