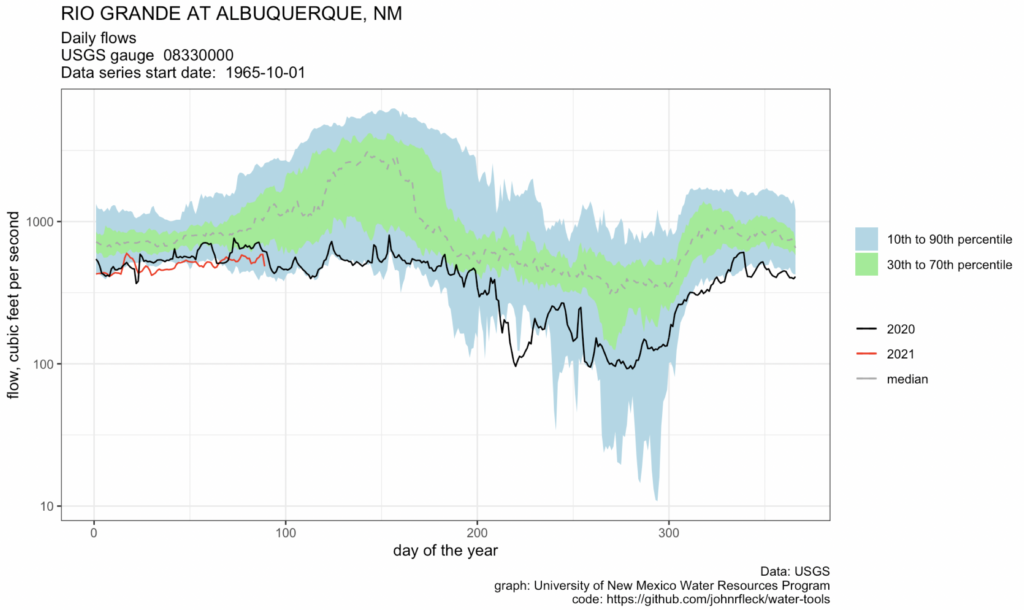

Rio Grande, Albuquerque, New Mexico; 1,430 cubic feet per second, May 6, 2021

Ima give this a fancy sciency-sounding patina: I walked a transect today across the ribbon of green the Rio Grande provides through the heart of Albuquerque.

I’m trying to think through what I have come to understand as the fundamental choice we face as climate change depletes the river.

We will have less green:

- Which green do we save, and which must we give up?

- How do we, as a community with different values, institutions, and interests, make the necessary choices?

- What are the roles of collaboration, law, and raw political power?

In my journalism and academic work, I’ve been caught up for a long time in some categories that, in Albuquerque, seem increasingly unhelpful – “agriculture”, “municipal use”, “the environment.” The categories line up pretty nicely with the government agencies, the rules and regulations, we use to manage the water resource, along with the conceptual categories of “natural” and “unnatural”.

But they’re not quite working for me right now.

A morning at the river

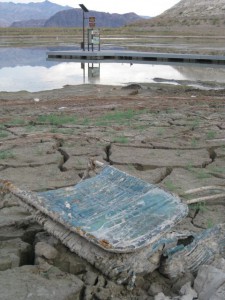

For a short shining instant, the Rio Grande through Albuquerque is up. We’re all scared shitless about the doom to come this summer as the water runs out, but in the dawn light today the cottonwoods were shimmering as I walked one of my favorite paths north of Albuquerque’s old Route 66 bridge.

I was too wrung out from stress-riding my bike this week, and stress-zooming my job, so I decided to skip my usual morning ride to the river. Instead I gulped the second cup of coffee and drove down to one of my favorite bike ride destinations along the Rio Grande. I realize gulping coffee and scarfing down my breakfast in order to jump in a car and hurry somewhere to relax is cognitive dissonance writ large, but I made it by sunup and the water, and the green, were a salve.

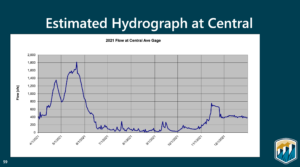

Projected Rio Grande flow at Albuquerque’s Central Avenue Bridge. USBR, April 2021

At the bridge, the river’s flowing 1,430 cubic feet per second as I write this, which will mean nothing to most of you but to me means a lot. The Bureau of Reclamation’s Annual Operating Plan, presented at a mid-April f’ing Zoom call (pdf here, technically I think Microsoft Teams because Feds, but still f’ing) projected decent flows through early June before the bottom drops out. Sitting on a bench by the river (see picture above) I could hear the drone of Route 66 cars in the background and the ripply sound of water at my feet. Enjoying it while I can.

A half mile north of the Central Avenue Bridge, the Atrisco siphon this morning was pushing out 80 cfs into the Arenal Main and the Armijo Lateral, a pair of distributary canals that substitute in this coupled human and natural system (we actually call them “CHANS”) for the role a braided river channel might have played in spreading life across the valley floor. Again, not a meaningful number unless you live in the South Valley, in which case it’s the lifeblood of your part of the CHANS.

Categories – unhelpful

My old categories – “agriculture”, “municipal use”, “the environment ” – aren’t quite connecting up for me now with the question I see about the distribution of green.

What we call the “bosque”, the riparian strip between the levees, is profoundly “unnatural”, the vestige of a flood control system that robbed the valley floor of high spring runoff but left a single strip of land through the city with a high enough water table for phreatophytes to thrive, at least for a time. Unnatural, whatever, I value it enormously, as do the black-headed grosbeaks who were the highlight of the bird list I made on my morning walk.

For the saltgrass marshes that used to spread across the valley floor, we’ve substituted small-parcel irrigation of land around houses – the word “agriculture” is right, but misleading. This is not Iowa, nor the Imperial Valley. Thousands of people do this, one at a time, and net cash farm income here is negative. But ah, the green. They’re clearly doing it for other reasons that we’ve not been very good at incorporating into our water policies.

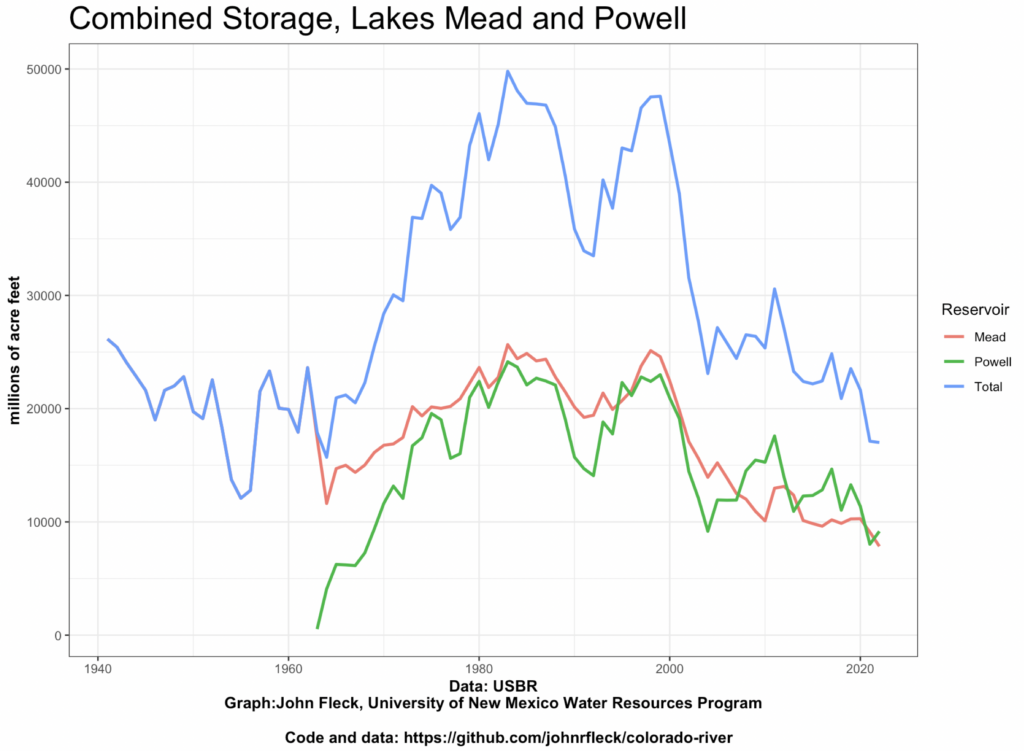

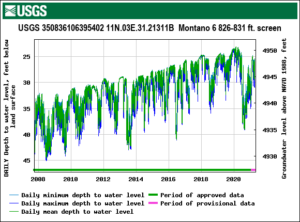

Just up the road, in an area we call “Los Griegos” that’ll likely be central to the next book, a city well field drilled in the 1950s still pulls water from the aquifer for use in the urbanized part of the city. These days its use is minimal, but with the community’s water utility in “drought reserve” operations last year, the Griegos field pumps pulled 3,000 acre feet of water from the ground for neighborhoods like mine. What water I use indoors ends up, via the wastewater treatment plant, back in the river. What water I use outdoors is spreading more green. As you can see from the graph, the aquifer in general has been rising in recent years thanks to Albuquerque’s success both in conservation and in shifting to use of imported surface water, but last year’s drought was a clear setback.

Just up the road, in an area we call “Los Griegos” that’ll likely be central to the next book, a city well field drilled in the 1950s still pulls water from the aquifer for use in the urbanized part of the city. These days its use is minimal, but with the community’s water utility in “drought reserve” operations last year, the Griegos field pumps pulled 3,000 acre feet of water from the ground for neighborhoods like mine. What water I use indoors ends up, via the wastewater treatment plant, back in the river. What water I use outdoors is spreading more green. As you can see from the graph, the aquifer in general has been rising in recent years thanks to Albuquerque’s success both in conservation and in shifting to use of imported surface water, but last year’s drought was a clear setback.

And it is worth remembering that the imported water (Colorado River Basin transbasin diversion) just means less green in that basin.

Sorry, Colorado River Delta. It’s all about shifting the green around.