Rio Grande at Albuquerque’s Central Avenue Bridge, 8 a.m. July 28, 2021

A robust July monsoon has allayed our worst fears about central New Mexico’s Rio Grande.

Is it really a “monsoon”?

Back in the days when my paid gig was writing newspaper stories, I loved writing about the monsoon, and every time I did I would get helpful feedback from readers anxious to explain that I was a doofus and didn’t know what I was talking about, a monsoon, no way!

While they may have been right about the doofus part, with respect to the monsoon part, yes way.

Here’s Ben Cook and Richard Seager by way of explanation:

The North American Monsoon (NAM) may be a poor relation of the majestic Asian monsoon but is nonetheless a real monsoon that provides important rainfall to Central America, Mexico and the interior parts of the southwestern U.S. (primarily Arizona and New Mexico). In Mexico and Central America the NAM is critical for water supply and agriculture since winter precipitation in these regions is so small. In the southwest U.S. winter precipitation, arriving at a time of low evapotranspiration, is critical to water supply but the NAM precipitation remains important for soil and groundwater recharge, ecosystems, rainfed and rangeland farming and for fire.

How has this year’s monsoon helped central New Mexico’s Rio Grande?

When last we visited on this topic two weeks ago, I’d just completed a swift bike ride to watch the river dry. Since then, we’ve had two weeks of wet.

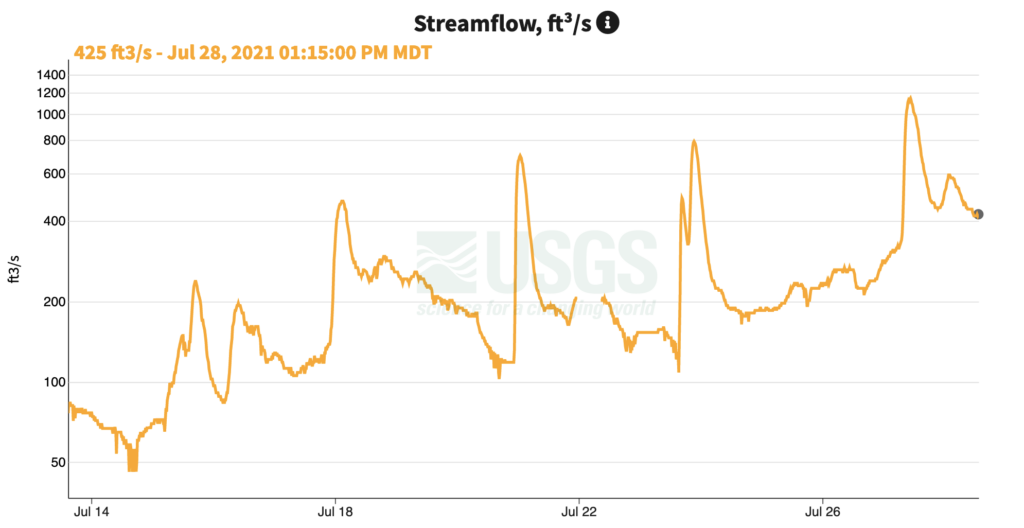

Each one of those little spikes represents runoff from a rain event somewhere in the watershed between the Central Avenue Bridge in Albuquerque and Cochiti Dam to the north. Our monsoon’s spotty that way – the “official” Albuquerque rain gauge at the airport has recorded just a third of an inch of rain during that time. But every couple of days it’s rained somewhere in the watershed feeding the river – sometimes a lot.

(It has been accompanied by tragedy. People with no home of their own often take up residence in Albuquerque’s flood control system. Three people died last week in one flash flood – see Elise Kaplan’s thoughtful effort to memorialize them. Our flood control infrastructure is great at protecting our city, but it has this dark side.)

The latest I have heard in conversation with water management folks is that the rains may have bailed us out of the river drying in the Albuquerque reach – we’re at this point unlikely to be writing about “the first time the Rio Grande has dried through Albuquerque since 1983”, which many of us have been doing.

But what about Elephant Butte?

The good news is that a lot of this monsoon water – flowing past Albuquerque and contributed by arroyos downstream – is making it to Elephant Butte Reservoir, which provides storage for downstream users in southern New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico.

The bad news is that Elephant Butte is really, really big, and really, really empty, and the monsoon inflows are tiny compared with what we need, which is a big winter->spring snowmelt.

A month ago, modelers at the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation were projecting Elephant Butte would bottom out at about 10,000 acre feet of storage in early August. It’s a 2 million acre foot reservoir. That’s just a half a percent full. That would have been the lowest since August 1954.

Updated model runs, incorporating the burst of monsoon moisture, now suggest Elephant Butte will bottom out at around 60,000 acre feet of storage sometime in the first part of August. That’s still just a hair above 1 3 percent full, which illustrates a central feature of the monsoon’s role in Rio Grande water supply: Compared to winter snowpack, monsoon rains’ contributions are tiny, only playing a minor role.

But coming at the right time, they nevertheless matter.

(Huge thanks to Carolyn Donnelly and Mary Carlson at the Bureau of Reclamation for modeling run data and helpful explanations. Tons of data in the right hand rail here.)