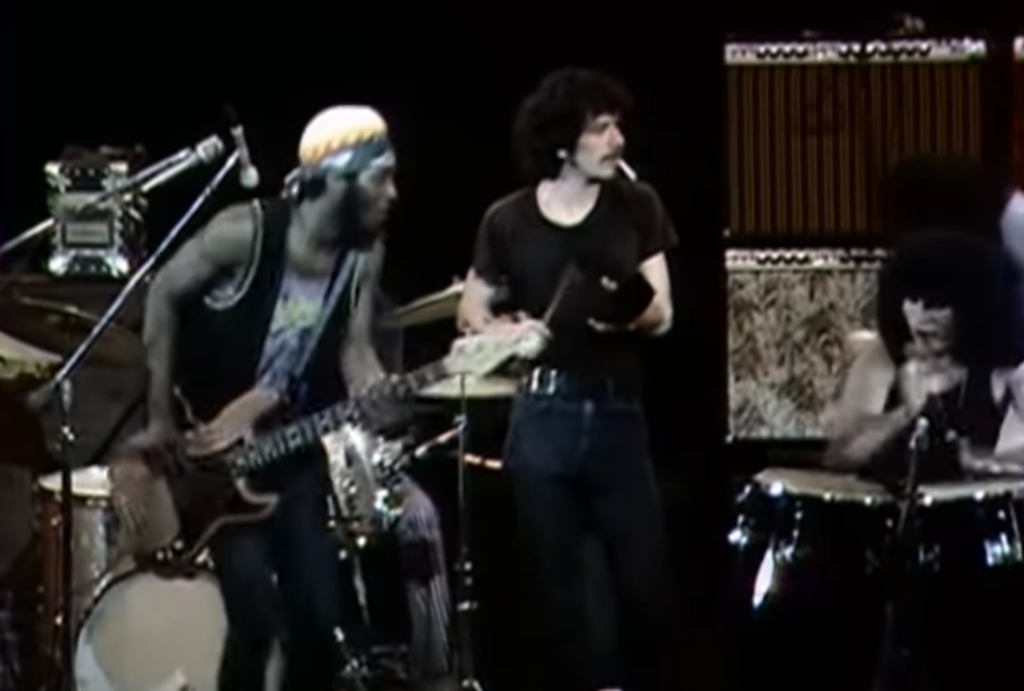

Mount Taylor in the distance, the Rio Puerco Valley in the foreground. Note growing number of water bottles on the bike frame.

In the Time of Pandemic, the ability to refill my water bottles has become an unexpected bike riding constraint. Worst case, if I couldn’t find a drinking fountain, I used to pop into a Kwik-E-Mart and buy a bottle. So, yeah, pandemic, amiright?

I hate those water pack things, and the discomfort of throwing extra bottles in those goofy back pockets on my cycle shirts. So I spent a bit of the afternoon yesterday (which was, I note for the record, a Saturday, if you’re losing track) installing a new bracket on my bike frame so I can carry more bottles.

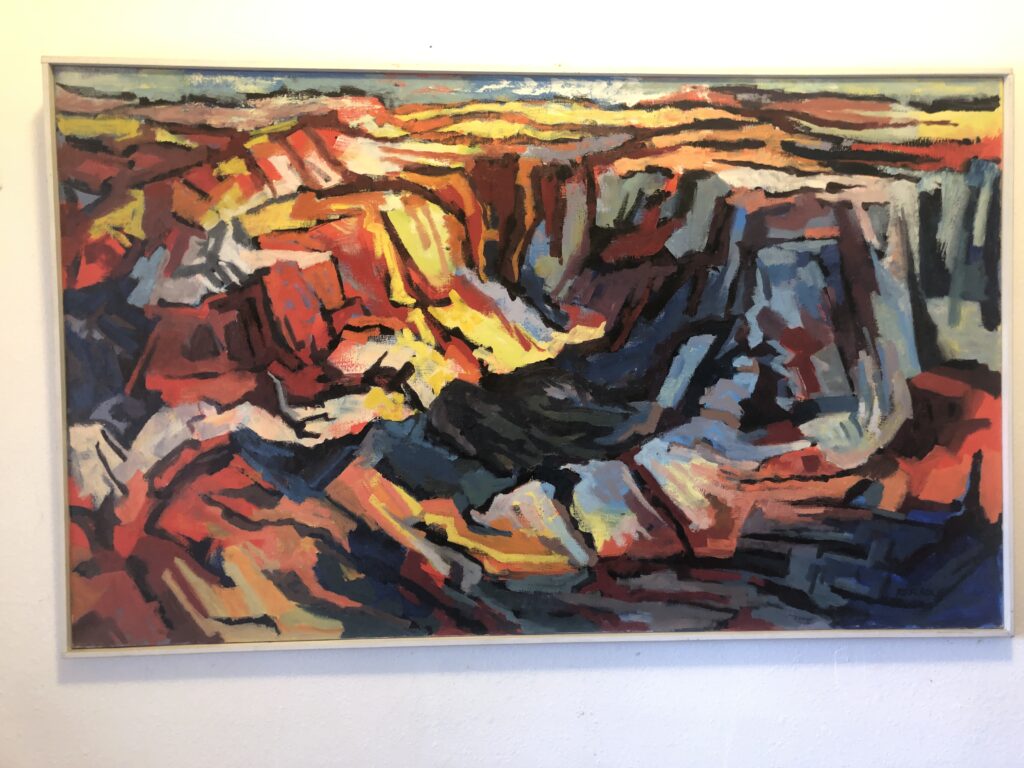

Thus it was this morning that, with a half gallon of water strapped to my frame and pockets overfilled with Lissa’s ferociously potent oatmeal cookies, I found myself on Shooting Range Road on Albuquerque’s farthest western fringe. The mesas on Albuquerque’s west side take two steps down to the river, and the uppermost bench is largely devoid of human habitation, save the old Double Eagle Airport, the “Compost del Rio Grande” where Albuquerque spreads its sewage solids out to dry (“rich in organic matter, nitrogen and trace minerals“), the city’s emergency winter shelter for people experiencing homelessness, and the shooting ranges.

Mostly its just wonderfully scraggly desert. Even when there isn’t a pandemic, it’s got no Kwik-E-Marts, so I’d never ridden out Shooting Range Road. But now I have cookies and a half gallon of water!

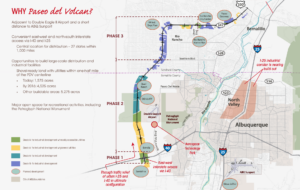

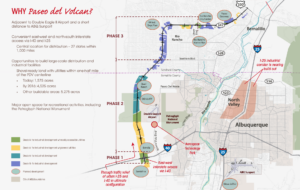

the fading dreams of Paseo del Volcan

Years ago, when I was young and racy, we used to ride out what was then called Paseo del Volcan (because it circles Albuquerque’s west side volcanoes). A few years back, they renamed it “Atrisco Vista” and planned a new “Paseo del Volcan”, a loop rode west of Albuquerque, studded with new housing developments and economic opportunity.

This was a fading idea before the 2008 economic shitstorm, and never unfaded in the years that followed. But lordy we’ve got some nice powerpoints and promotional graphics – “connectivity, access, economic growth“.

Here Lies Shorty

In the meantime, it’s a great place for Albuquerque to spread its shit to dry, and shoot. I found myself late this morning at the old Wild West action shooting range, complete with old timey cemetery up the hill from the shooting range – closed, sadly, because of the pandemic.

One of the fun things about these long rides along the vast open upper mesa is exploring Google maps quirks. Last month it was the Mystique Food Truck, and today’s outing included a uranium mine and a Wendy’s, out in the middle of the empty. I cannot tell you for sure that there is no uranium mine next to the drying sewage solids (it might be underground, yes?) but there for sure was no Wendy’s here – unless it’s underground too?

no Wendy’s there

For much of the first months of the pandemic, my mental quirk had been to stare at the cupboards and worry about running out of food. With our offspring handling the grocery shopping for their elders, this really hasn’t been much of a worry of late, so the quirk has transferred to worrying about running out of water on a long bike ride. Two-plus months in, the bike rides are getting a good deal longer, and the weather a good deal warmer.

So I spend hours on line pondering mounting brackets to carry extra bottles, and hunt for the largest bottles. By the time this project is over, I’ll be able to carry a gallon!

There are whole new areas of Albuquerque’s far west side to explore, with nary a Kwik-E-Mart or Wendy’s in sight. The only constraint now will be how many oatmeal cookies I can carry.