Koda, co-author with Bob Berrens and John Fleck, of the forthcoming book The Rio Grande and the Making of a Modern American City, to be published as soon as we can write it and find a publisher.

My co-instructor Bob Berrens and I added a slide this morning to our welcome lecture for first-year students in the University of New Mexico’s Water Resources Program, hoping to foreshadow two questions we’ll be asking the students over and over and over and over this semester:

Bob: That sounds great, how are you going to pay for it?

John: X sounds great, why don’t they just do X?

The welcome lecture includes all the usual “read the syllabus”, and “no this won’t be on the quiz, we don’t have quizzes”, and such, as we shove aside the bureaucratic detritus of academia so we can get down to the business of talking about water.

The headline for this year’s class (yes, I am an inkstained wretch, see blog title, our syllabus has a headline) sums up the dilemma:

There’s less water. What do we do?

There’s less water. What do we do?

It’s the ninth or tenth time we’ve taught the class together, depending on how you count, and we love doing it because we are good friends who have spent the better part of that decade talking about water in and out of class, we still don’t really understand all the things, and teaching helps us sort through our own confusions.

We have our lists of things we hope to share with the students – the challenge of market and non-market values of water, the strange land of municipal pricing, the even stranger land of agricultural water use in its many forms and flavors, the tools of water measurement, the wisdom of Elinor Ostrom and Ronald Coase in analyzing water governance structures, the story of the orange groves of Upland, California, where I grew up.

Through it all, as we’re building the scaffolding, we’re also asking the students to use that same scaffolding to begin to analyze a question. A month or so back, while walking with Bob’s dog Koda around Altura Park (which sits midway between our two houses), we settled on this year’s question.

There’s less water. What do we do?

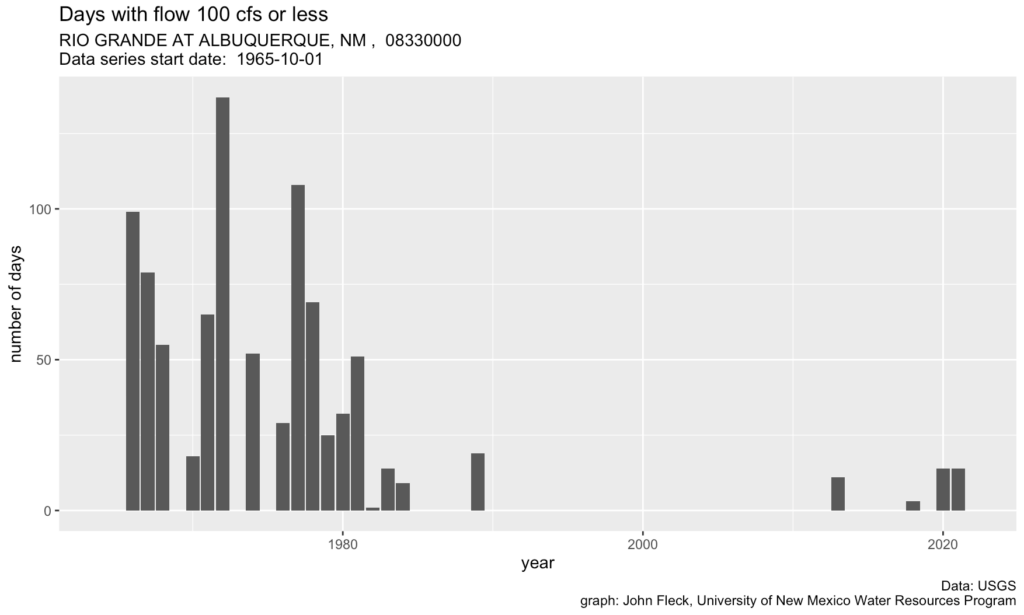

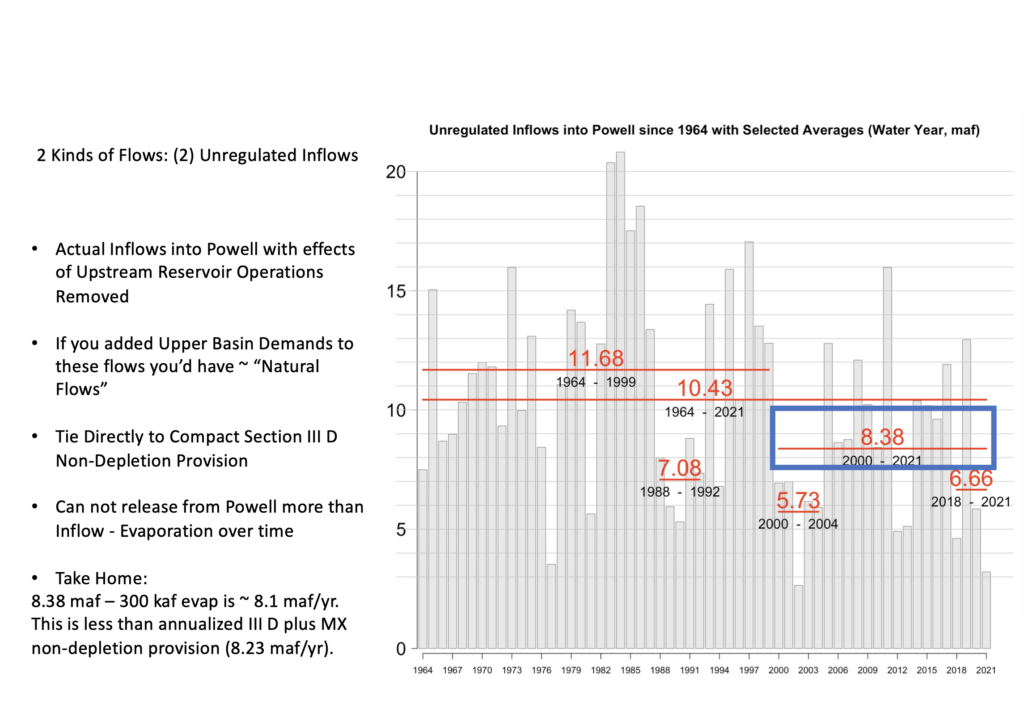

As the reservoirs behind Hoover and Glen Canyon dams on the Colorado drop to record lows, as irrigators in central New Mexico struggle to water crops after an early start and early end to their irrigation seasons, as I spend countless hours with reporters from across the country looking for help understanding all of this, as my own river goes dry, it remains the central question. And I do not know the answer.

I’ve got some schtick involving case studies I’ve written over the years about successful conservation and collaborative water-sharing agreements, and about the importance of being attentive to science, however inconvenient. I will happily share all of this with our students over the coming semester. I really believe it, and I think it’s all important, and I feel so privileged that students want to sit and listen to me yammer on about it for hours on end!

But I’m mindful of Bob’s and my questions, which really are important – how are we going to pay for the things that need to be done, and why haven’t they been done already?

Let’s assess the farmers to to pay for it.

The point of Bob’s question is the more obvious – many solutions we might contemplate are costly, and understanding how we pay for them (or fail to come up with a mechanism to pay for them) are at the heart of many of our dilemmas. We need to think through these questions carefully. This is central to the new book Koda, Bob, and I are beginning to write. Bob’s insights about financing mechanisms are one of his most important gifts to my thinking.

Why don’t they build a pipeline/canal to the Mississippi?

My question – why don’t they do “X” – is more obscure, because in one common usage it isn’t really even meant as a question. Often, a person posing it really means “X should be done“. But I’ve found it incredibly useful, going back to a long career in journalism, to really try to pose it as a question – to really understand the reasons X has not been done.

In some cases, upon closer inspection, I find they haven’t done X because it’s a really bad idea for reasons I hadn’t thought through. In other cases, I find that X has costs, or downsides, that I hadn’t thought through. In other cases I find obstacles that, however good an idea X is, must be overcome.

Sometimes (see above), X hasn’t been done because we have no way to pay for it. I’m pretty sure it was Koda who pointed out that Bob’s question is really a particular case of my more general formulation.

I pretty much never find that they haven’t done X because it never occurred to them.

Darkness at the park

At Bob’s suggestion (I have found these to be useful), I was rereading this morning a 1959 essay by Charles Lindblom called “The Science of ‘Muddling Through’“. It provides a great framework to explain why, the more time I have spent in the study of water policy and governance, the less clear the answers have become.

Lindblom suggests that our desires for an omnisciently rational policy making process, while widely expected, is impossible – because of bounded rationality, and lack of clarity about how to weigh relative values (shared and unshared). So we end up muddling.

During the pandemic’s darkest last winter, Koda, Bob, and I were walking around the park in the cold dark of night. Halfway down the park’s north side, Koda alerted – there was something in the park. We couldn’t see it, but we have come to understand that Koda is far smarter than we.

I guess that’s my hope for the semester, that Bob and I might walk down the side of the darkened park and get some help from our students in seeing what is there.