Cochiti Main Canal, just south of Peña Blanca, New Mexico. Oct. 30, 2021

Peña Blanca, NM – The Cochiti Main, winding through the village of Peña Blanca, was still flowing Saturday morning with some of the last of this year’s irrigation water destined for farms to the south.

I’m a bit jammed up in my effort to return to writing (see below for the “some personal news” portion of the post), so I loaded up a bike Saturday morning and drove north to what we might describe as one of the key “field areas” for The New Book.

Peña Blanca is an old Spanish village wedged between the indigenous communities of Cochiti Pueblo to the North and Kewa (formerly called by some Santo Domingo) Pueblo to the south. I’m actually far more interested in Cochiti and Kewa, but as sovereign nations they’ve closed down access during the pandemic, and a bike ride is a bike ride. So Peña Blanca it was.

The stray cow of

Peña Blanca. Photo by John Fleck, October 2021

Turning down Abrevadero Road I crossed the Cochiti Main and dropped down past alfalfa fields to the source of the day’s minor drama – a firefighter from nearby Cochiti on the phone trying find the owner of a stray black calf wandering on a street that is actually named (I do not kid in such matters) “Acequia Road”. The firefighter smiled at me as I rode slowly past, the calf gave but a brief glance before going back to doing calf things.

There is evidence here for my frequent claim that I am a “city kid”. When I explained to a friend, who grew up around manure, that it was my first such encounter in many years of cycling, he expressed surprise. But my city kidness is an empirical observation. I am comfortable asserting that I have never in my life lived within a mile of a cow.

According to historian Jacobo Baca, Peña Blanca in its modern form dates to a 1754 land grant by New Mexico Gov. Francisco Antonio Marín del Valle to Juan Montes Vigil. I say “modern” because the people of Cochiti Pueblo immediately to the north have occupied the area for what we like to call “time immemorial” – a time beyond the reach of memory, in some sense forever.

In the human history of this place, 1754 is the recent past.

It’s fair to say the land tenure in this area, like much of the Rio Grande Valley, is and has been a deeply contested thing, and I do not claim the expertise or standing to explain it here. Suffice to say the Pueblo communities have a robust history of contesting colonizers on their land, sometimes successfully, sometimes not, and some of the most interesting of those struggles have happened here.

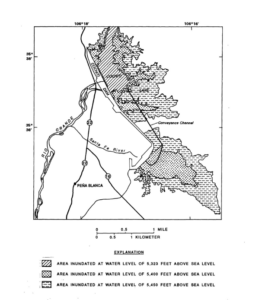

Cochiti Dam. From Paul Blanchard, USGS

Cochiti, Peña Blanca, and Kewa represent the Rio Grande’s introduction to what we in New Mexico call “the Middle Rio Grande”. The river once opened out of White Rock Canyon and spread across a widening valley floor – a beginning now dramatically and importantly inundated behind Cochiti Dam. Today a “recreation pool” floods the “time immemorial” summer homes of the Cochiti people. As I said above, the Pueblo people’s contestation of colonization has sometimes been successful and sometimes not. Cochiti Dam is one of the “nots”.

Today, rather than the graceful widening of a river slowing to meet its valley, we’re left with a concrete spigot at the base of a huge earthen dam.

Cultural implications aside, on purely water engineering grounds Cochiti Dam is some crazy shit. It runs nearly four miles from northwest southeast, plugging the Rio Grande, before making a sharp right turn for another mile to block the Santa Fe River. When they began storing water behind the dam in 1973, it raised the water table so much that the Santa Fe River downstream from the dam, once intermittent, became a perennial stream. The dam turned land on the valley floor, which the people to Cochiti had farmed for time immemorial, into a swamp.

It is impossible to understand the relationship between the Middle Valley and its river without coming to terms – hydrologically, institutionally, culturally – with Cochiti Dam.

Some personal news

bookshelf at the new office

I sorta quasi-officially finished up my five years’ tenure as director of the University of New Mexico Water Resources Program Oct. 22. I’m still helping the new director, Scott Verhines, with the transition and still teaching. But also undertaking the mental shift to the next thing.

I’m returning to a title and gig I had while I was writing Book Two – “Writer in Residence”, this time based at the Utton Center, a water policy group at the University of New Mexico School of Law.

The new office comes fully equipped with its own copy of Ira Clark’s Water in New Mexico, and I brought over the unkillable house plant (Sansevieria trifasciata) that Lissa gave me when I first moved into my last “writer in residence” office in the UNM Economics Department building. I’ve come close, but haven’t killed it yet, though I am happy to report that Utton Center Director Adrian Oglesby has offered to help water it.

I have found the restroom, and am making a leisurely task of becoming acquainted with the law school’s remarkable art collection.

The new gig is a chance to more fully focus on the thing that gives me joy – writing about water.

The WRP directorship was an awesome experience – working with grad students was definitely joyful. But it left me less time than I would have liked to think and write. (I guess I did write Book Three during my time as WRP director? But y’all know that Eric did most of the work, right?)

The New Book

This blog is my sketchbook. Writing in private has never worked for me – a craft honed by a life writing for newspapers is a craft that has public execution at its heart. I say that by way of explanation that, while the stray cow of Peña Blanca will almost certainly not be in The New Book, the challenge posed by making sense of Cochiti Dam might be at the book’s core.

It is reasonable to think that it was here, just downstream from the confluence of the Rio Santa Fe and the Rio Grande, that John Van Dyke, whose ideas are likely to play a role in the book, first encountered the desert river valleys that were at the heart of his strange and wonderful book The Desert. Standing off by the side of the road at Cochiti Elementary School Saturday morning, seeing the dam’s sweeping form as it dog-legged across the Santa Fe – that’s why I go to places, and then write about them.

After the Rio Grande ripped through Albuquerque in the flood of 1941, it is easy to understand the motivation of the dam-builders. If Cochiti Dam is the middle valley’s great sin, we must also consider whether the dam was some sort of salvation.

My co-author Bob Berrens and I are still not quite sure how to explain what the new book is about, but we’ll get there.

More sketches to come.

Second, it means that it is not helpful to continue to talk about closing the gate. There is a long history of people moving out here to the West and then wanting to turn around and close the gate. Unless you are a Native American and your family has been here since time immemorial, you do not have the moral high ground to close the gate. There’s something like 8 billion people on the planet. Our cities are going to continue to grow.

Second, it means that it is not helpful to continue to talk about closing the gate. There is a long history of people moving out here to the West and then wanting to turn around and close the gate. Unless you are a Native American and your family has been here since time immemorial, you do not have the moral high ground to close the gate. There’s something like 8 billion people on the planet. Our cities are going to continue to grow.