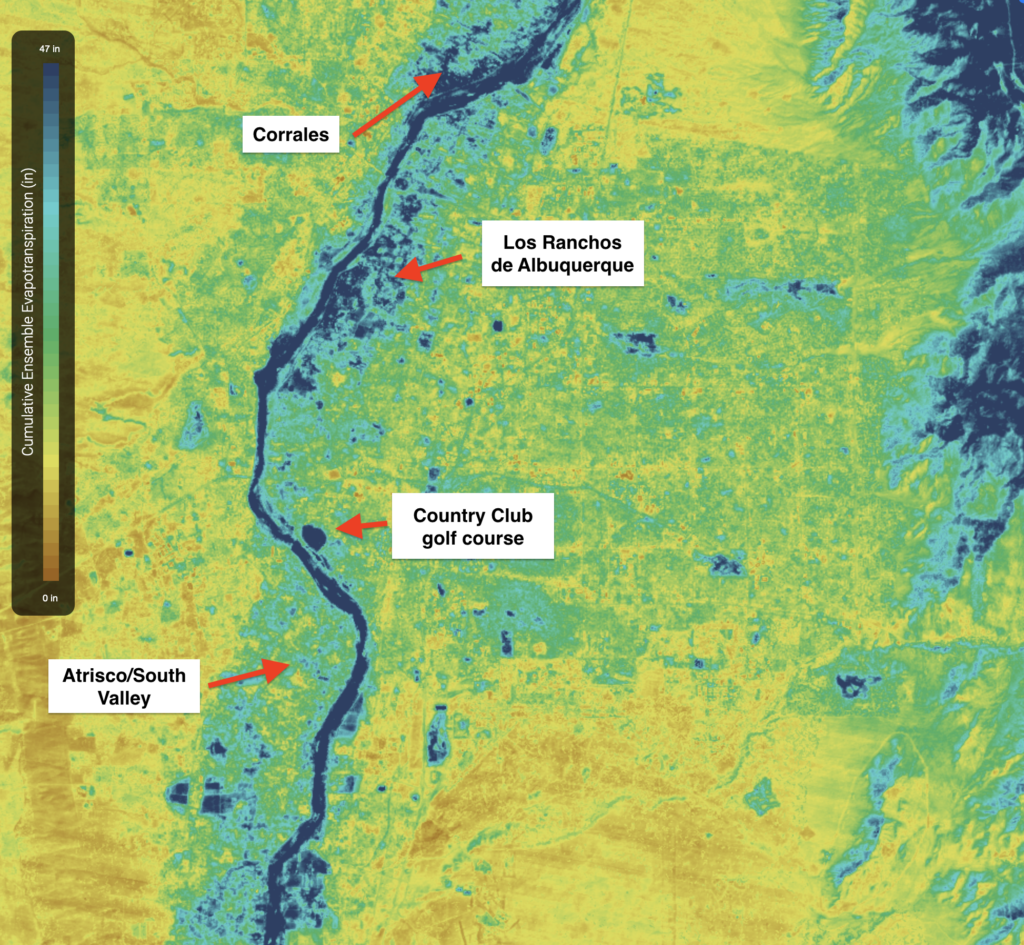

Albuquerque water use, via OpenET

I’ve been spending an inordinate amount of time the last few weeks pointing and clicking on the new OpenET project’s “data explorer”.

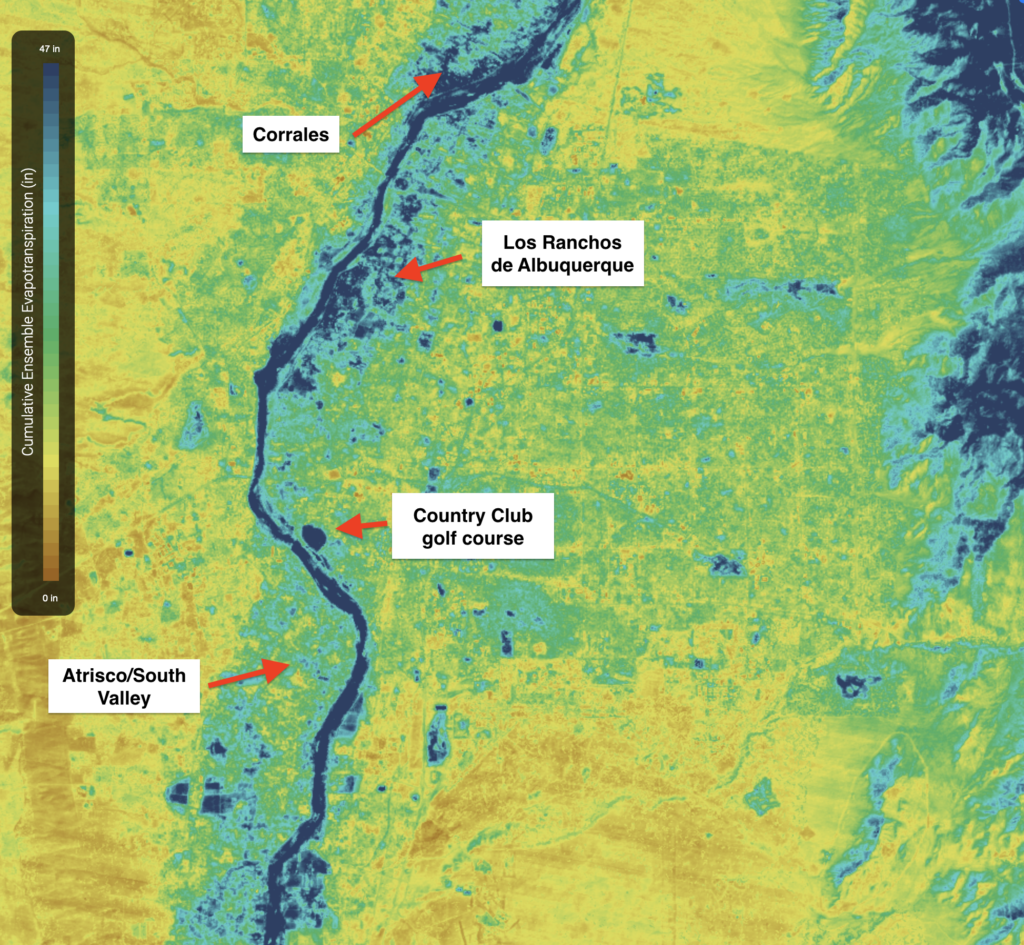

Using satellite data and magical algorithms, OpenET allows me to look at an arbitrary bit of land and retrieve an estimate of the amount of “evapotranspiration” – essentially outdoor water use – for recent years.

How green is Albuquerque’s Country Club golf course? How does the water use in the relatively affluent valley floor communities of Los Ranchos de Albuquerque and Corrales compare to the less affluent Atrisco and points to the south in what we call the “South Valley”?

Data wise, we have a pretty good handle on how much water Albuquerque’s largest municipal provider, the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority, is delivering to customers each year, and how much of that water is returned to the river from the southside sewage treatment plant. But sometimes when I look at their data, I feel like I’m trapped in the old joke where I’m drunk and looking for my keys under a streetlight. (“Is that where you lost them?” someone asks me. “No, but it’s the only place where there’s any light!”)

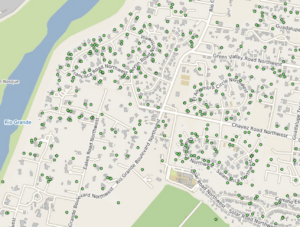

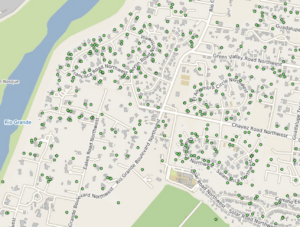

Domestic wells (green dots) in Los Ranchos de Albuquerque

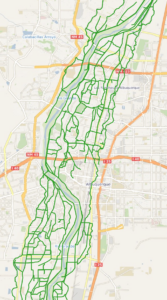

Consider, by way of example, a patch of Los Ranchos I’ve been looking at for a while as I try to make sense of Albuquerque water use. I’ve been drawn to Los Ranchos because its one of the greenest places in our desert city. In addition to municipal water for indoor use, which is metered, many of the homes have access to irrigation ditch water (and a tax break if they put that water to agricultural use). Irrigation delivery here is not metered. Many of the homes also have domestic wells drilled into the shallow aquifer, which are also generally not metered.

So, in summary – super green there, looks like people are using a lot of water. How much? We don’t know, it’s beyond my streetlight!

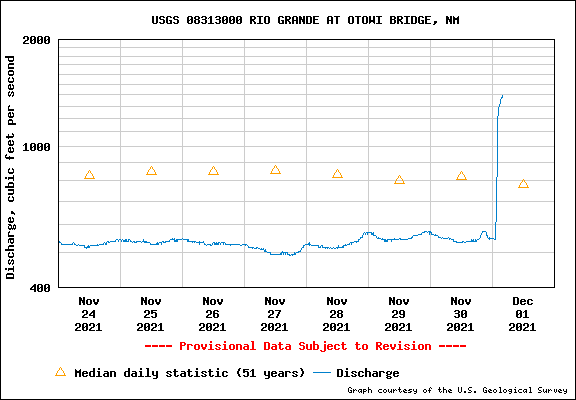

Enter OpenET, which allows one to highlight a polygon on a map and spit out consumptive water use, by month, back to 2016.

My little OpenET Los Ranchos test plot is about 450 acres between Rio Grande boulevard and the river, stretching between Montaño Road and the northern edge of a leafy be-lawned neighborhood called Tinnin Farms. This area of Los Ranchos is one of the more affluent areas in the greater Albuquerque metro area. By my rough “danger Fleck doing OpenET math” calculation, consumptive use of water added to landscapes in this area (above and beyond precipitation) amounted to about 1,300 acre feet of water last year.

Who gets to use what water?

In one of the papers I’m always pushing on my students, the late Elinor Ostrom highlights a set of key characteristics – “design principles”, she calls them – of successful common pool resource management regimes. Ostrom is importantly not arguing for any particular best solution to these problems. (The paper’s title is “Why Do We Need to Protect Institutional Diversity“.) But in her lifetime of work, the Nobel laureate identified key stuff that tends to show up in places where people have succeeded at the challenge of sharing a limited resource to maximize its benefits to a community.

Ostrom’s design principles ask a bunch of useful questions, and I’d like to paraphrase as they apply to my little toy example: who will be allowed to use what amounts of water, and when? How will rules over this use be monitored and enforced, and how will conflicts be resolved?

I would argue that in my little Albuquerque Rio Grande valley floor neighborhood, we lack a full set of these tools. We have one set of rules for irrigation water, a second set of rules for municipal water, and a third set of rules for domestic wells. For most of this, we lack enforcement mechanisms or fail to use those that the law might allow. The three management rulesets do interconnect in technical legal ways that might allow them to be integrated into a single management approach. Also, unicorns would be so cool!

In my book Water is For Fighting Over (not), I spent a good deal of time on what I think is one of Ostrom’s most important points – the need for a shared understanding of what the resource is and how it is being used. In her thesis work, she tackled the development of shared water management institutions in a place prosaically called “West Basin” west of downtown Los Angeles:

To solve a common pool resource problem, you first need a shared understanding of what the resource is. This sounds simple, but in the case of the West Basin, it was not.

This is one of the most important pieces of my Colorado River work – why my favorite basin peeps all seem to have these amazing collections of spreadsheets on their hard drives that they use to help sort out questions. But that’s one of those “drunk looking for keys under the streetlight” things. One of the reasons I love working on Colorado River issues so much more than the Rio Grande is because there’s so much more light!

This is why I’m so excited about OpenET. If it works – which means both that it has to be technically solid and also earn our trust – it can shed some of the light I think we need.