tintenfleck

Reader Christian Kuehnke writes:

Did you know that “fleck” in German means “stain” (like in inkstain) in English and “inkstain” would translate to “Tintenfleck” in German ? 😉

tintenfleck

Reader Christian Kuehnke writes:

Did you know that “fleck” in German means “stain” (like in inkstain) in English and “inkstain” would translate to “Tintenfleck” in German ? 😉

Reclamation’s ambitions writ large – the “Fall-Davis Report”

In complex multi-party negotiations like the Colorado River Compact process, it is rare that major progress or breakthroughs happen during one of general sessions. Instead, real progress is more often made during the more candid discussions between smaller groups of negotiators during breaks, after-dinner discussions, and occasionally sub-committees. Most of these discussions in these venues are not documented in formal minutes.

Thus it is with the development of the Colorado River Compact.

But in the shadows of those committee meetings in the early days of the Compact’s negotiation a century ago, we can see a few key features begin to emerge.

While Washington D.C. was being pounded by the Knickerbocker Storm on Friday January 27th and Saturday, January 28th, 1922, the Colorado River Commission met four times, twice each day. The minutes show that the Commission accomplished very little during these meetings. They had “general” discussions and heard from members of Congress, including Senator Key Pitman from Nevada and Representative Phil Swing from California’s Imperial Valley, both of whom would have significant roles in the development of the river. The real action was taking place in the water availability and water requirements committee.

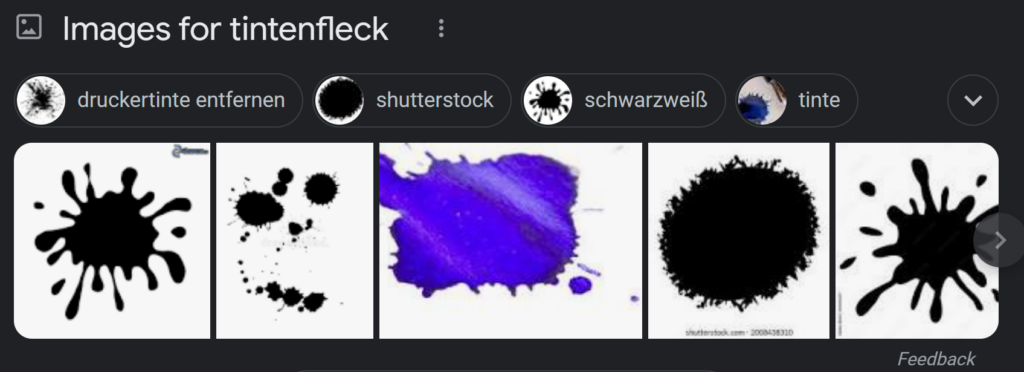

Hoover had directed Arthur Powell Davis to work with both committees. Davis invited the committees to meet at the Interior Department Building where they would have access to the authors and underlying data that went into the “Fall-Davis” report, a comprehensive study of development of the Colorado River Basin prepared by the Reclamation Service at the request of Congress.

Davis and Hoover were hoping the total water requirements for present and future irrigable acreage as identified by the requirements committee would be less than the water available as identified by the availability committee. There would then be a basis for apportioning water use among the seven states. Davis knew that based on the Fall-Davis Report, this result was possible. It all depended on whether the states would accept the data presented in the report.

Davis was hoping that a Colorado River Compact would lead to the authorization of the Fall-Davis Report’s signature projects, the All-American Canal, and a high dam in Boulder Canyon, which in turn would reenergize his struggling agency. Although the Reclamation Service had already achieved some major engineering feats such as the Roosevelt Dam on Arizona’s Salt River and the Gunnison Tunnel in Western Colorado, the agency had a fundamental problem. It was created by Congress in 1902 to help “reclaim” arid Western lands by providing reliable and affordable irrigation water, but farm economics were not working. Farmers receiving water from Reclamation projects were struggling to repay the federal government for the cost of building the projects.

Davis saw a new opportunity. A 700’ high Boulder Dam would produce a huge amount of hydroelectric power and there was a nearby market for the power, the fast-growing City of Los Angeles and its suburban neighbors. Hydroelectric power generation on Reclamation facilities would be in high demand in the West’s growing urban centers and the revenues it would produce would make projects both economically feasible and politically attractive. But, as Davis and his Reclamation Service colleagues would soon find out, power generation on federally owned facilities would bring in a new set of complications.

In prior appropriation states, power generation was a beneficial use, but not a beneficial consumptive use. One of Carpenter’s major concerns was that the water rights created by these large projects would command most of the flow of the river, interfering with upstream uses for irrigation and domestic purposes. Further, by the early 1920s there was already stiff competition for developing power in the canyons of Western rivers. Just a few months before that January meeting, a private company intent on developing hydroelectric power, Southern California Edison, provided funding for the USGS to install a river gage at a location on the Colorado River most of the compact commissioners had never heard of, Lees Ferry, Arizona.

The goal of committees was to complete their assigned tasks and report back to the full commission on Monday morning, January 30th.

Stay tuned.

Previously: A century ago, Colorado River Compact negotiations begin

Tony Davis had a great story in the Daily Star over the weekend on the allure of desalination of ocean water as Arizona struggles with shrinking Colorado River supplies.

Tony’s excellent work on this question susses out the problems:

A few key bits.

First ASU’s Kathy Ferris:

“We have to start taking care of our own house before we can be asking people to put money into new supplies,” said Kathy Ferris, a former Arizona Department of Water Resources director and an Arizona State University research fellow. “We’re not doing that. It’s too hard to say no, too hard to say we’re not going to do business as usual. Instead of trying to clean house, it’s easier to say we will go out and find more water and keep doing what we’ve been doing.”

USC’s Amy Childress:

Amy Childress, a civil-environmental engineering professor at the University of Southern California, has spent 20 years researching various processes using membranes for desalination, wastewater reclamation and water treatment in general. Asked about the potential for desalination by Arizona, she said, “I guess the key thing is, before going to ocean water desalination, qe have to ask have we done all the conserving we can do? Have we maximized wastewater reuse? Are there are opportunities to import that could be easier?

“I didn’t hear that whole plan out of the Arizona governor. I just heard something that seems like a quick fix, and I don’t think his plan is a quick fix,” Childress said.

A note on the journalism….

If you’re reading this, you’re probably someone who cares about western water issues in general, and likely the Colorado River Basin in particular. Tony’s work (along with that of quite a few a other folks working in the basin) is incredibly important to our shared understanding of the issues we face.

I don’t know if the link above will work for non-subscribers. I’m a paying subscriber to the Star. I know it’s hard for an individual to pony up to pay for all the publications doing this, but if you have the money to contribute to this ecosystem, do it. Subscribe to the Star, or subscribe somewhere.

If you’re one of my readers at the well-funded institutions working on these issues, get your institution to pay for a subscription! Journalism like this isn’t free to produce.

As the Colorado River Compact Commissioners gathered in Washington a century ago, a storm settled over the nation’s capital. Photo courtesy Smithsonian

Herbert Hoover’s words a century ago were chosen with care. Might it be possible, he wondered, for the state officials gathered around him that day “to agree upon a compact between the seven states of the Colorado Basin, providing for an equitable division of the water supply of the Colorado River”?

It was Thursday January 26th, 1922, at 10:00 AM, as the eight members of the Colorado River Commission met in Washington, D.C. gathered for the first time at the offices of the United States Department of Commerce. Over the next 11 months they would negotiate the details of the Colorado River Compact which they signed on November 24th, 1922.

“It is hoped that such an agreement,” Hoover added “… will prevent endless litigation which will inevitably arise in the conflict of states rights.”

Hoover, then the Secretary of Commerce, had been appointed by President Warren Harding to be the commissioner from the United States and lead the effort. In addition to Hoover, each state sent a commissioner appointed by its governor:

Hoover’s opening statement was carefully prepared.

While there is possibly ample water in the river for all purposes if adequate storage is undertaken, there is not a sufficient supply of water to meet all claims unless there is some definite program of water conservation.

In the language of the day, “conservation” meant something very different than its modern usage. It meant, quite simply, building dams to “conserve” water that would otherwise be “wasted” to the sea. But the enormity of the dams contemplated left an equally enormous institutional task – developing the rules needed to allocate, and therefore share, the river’s waters.

As to the federal role, Hoover mentioned four interests:

“The sole object of the Federal Government,” Hoover said, “is to secure development of the river in the interest of all.” After his opening statement, Hoover was formally elected Commission Chairman.

Each of the state commissioners gave an opening statement.

Hoover first turned to Colorado’s Carpenter, acknowledging his role in the creation of the commission. Agreeing with Hoover, Carpenter stated “the prime object of the creation of this Commission was to avoid future litigation among the states.” He added that “facts are always the basis of legal problems and hence the facts must be studied.” The need to avoid litigation and study the facts was a common theme to the statements of all seven state commissioners.

The commissioners then heard from Arthur Powell Davis Director the U.S. Reclamation Service and nephew of the legendary John Wesley Powell. Davis, who began studying the Colorado River Basin in 1895, impressed the commissioners with his knowledge of the Colorado River. He emphasized Hoover’s conclusion that with conservation the river had a sufficient supply of water to irrigate all lands that could be “favorably reached.” Davis suggested the Commission could successfully apportion the river’s waters among the seven states based on the number of irrigable acres in each state. Over the next six meetings, they would pursue this approach without success.

The Commission then heard from representatives of the Army Corps of Engineers, the Federal Power Commission, and finally the U.S. Geologic Survey. In a short statement, Nathan Grover, Chief of the Hydrologic Branch, told the Commission that the resources of his agency were at their disposal.

What he did not mention was that his agencies’ Colorado River experts, including E.C. LaRue, did not share Davis’ optimistic view that there was enough water for all. Instead, they would have urged the Commission to be much more cautious and conservative in allocating the river’s waters.

Before the meeting ended, the Commission appointed committees to look at the legal issues, determine the water supply available, and ascertain the demands for water. They also tabled a proposal by Arizona’s Norviel to create a permanent commission. By the end of the first meeting, it was clear that four individuals would dominate the Commission. Herbert Hoover, the confident and self-assured mining engineer, took command of the effort from the first meeting, but too often chose expedient results over a thorough understanding of the facts. Delph Carpenter, the brilliant legal strategist and father of interstate water compacts, fearing the power of centralized government and the societal changes being driven by new technology, fought for state sovereignty in an increasingly complex interconnected world. Winfield Norviel, the tenacious Arizona Water Commissioner, understood that unlike the six other states, the Colorado River system was the only source of surface water for Arizona’s future, but his negotiating style alienated the other commissioners. Finally, Arthur Powell Davis, the hands-on engineer who understood that a peace pact among the states would open the door to the development of a new generation of massive water projects his agency would build and operate. Like Hoover, he wanted to avoid the Commission getting bogged down on the facts. Now, with Grover’s acquiescence, he controlled the facts the Commission would use.

The first meeting ended on a positive note. Although the Commission would soon find out how challenging it would be to turn broad concepts into agreement details, the optimistic view of the water supply put forth by Davis, Carpenter’s legal discipline, and Hoover’s pragmatism would ultimately prevail.

As an omen of the future turmoil facing the river, that evening Washington D.C. was hit with a record snowstorm. A Nor’easter lashed the region, dumping over 30 inches of snow on the city, enough that the weight of the snow caved in the roof of the Knickerbocker Theatre, killing nearly 100 people. The storm became known as the Knickerbocker storm.

The Commission held two short meetings on Friday January 27th, then got together again on Saturday January 28th to begin the real work of hammering out a compact.

back when the Salton Sea was rising

A friend shared this, from the Sandia Lab News, circa 1955:

New Dyke Will Give Salton Sea Test Base Protection Against Rapidly Rising Water

The steadily rising water level of the Salton Sea in southern California is presenting a problem for the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission in seeking to safeguard test facilities operated by Sandia Corporation on the shores of the Sea.

Details here.

Yes.

But that’s not stopping me!

The Jan. 1 forecasts, courtesy of Angus Goodbody of the NRCS, for flows at Otowi (the head of New Mexico’s Middle Rio Grande Valley) and San Marcial (the tail) are for “normal” flows, where “normal” is defined now by the median of flows from 1991-2020.

The reason it’s definitely too early to be optimistic is that it’s just January! The remaining months in the winter snow accumulation season will either be wet, or they will be dry, and that will make all the difference. As Anne Marken, Water Operations Division Manager for the Middle Rio Grande Conservancy District, explained to the district’s board at yesterday afternoon’s meeting, “There’s a lot of winter left”.

There are a couple of good signs, though.

First, soil moisture in the headwaters region is substantially better than the previous two years, when dry soils and shallow aquifers took a big cut of the snowmelt before it ever got to the rivers. This is in part a result of a better 2021 monsoon season. (Click on the picture for a link to NRCS’s cool (new?) data map thingies).

Second, it’s actually snowed. The snowpack is not great, and has been concentrated along the western edge of the basin’s upper reaches, but it’s a pretty good start.

But see Marken’s “lot of winter left” comment.

For “normals” for this sort of analysis, the water management/forecast/climate community uses the mean and/or median over a 30-year window. This shifts every ten years, and for 2022 we now need to become accustomed to the 1991-2020 time window, shifted for this year’s forecasts from the 1981-2010 window we’ve been using.

In dropping the relatively wet 1980s in favor of the relatively drier teens, we’ve got a drier “normal” against which to compared.

NRCS is also shifting its normal forecasting, the numbers Goodbody publishes each month, from using the mean for the reported “normal” to the median. Statistics nerds will understand that the median better reflects the central tendency for skewed datasets like runoff, but I am not one of those people so thinking through the difference and applying it to my runoff intuitions makes my head hurt. Thankfully the NRCS’s Goodbody (I think of him as our “forecast data concierge”) shared a great new tool for comparing the two time periods and two different measures of central tendency.

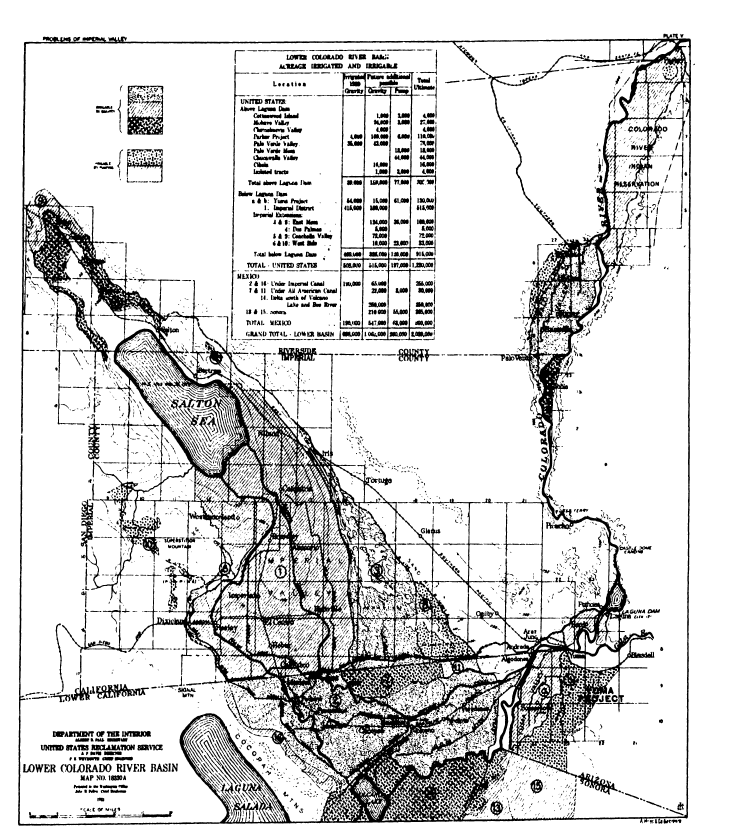

my 2021 rides in the heart of Albuquerque

In September 2019, my friend Scot and I did one of our more memorable “what happens if we turn here” bicycle rides.

In our endless search for what I call “longcuts” – the safest route, rather than the shortest – we followed a concrete flood control channel called the North Pino Arroyo up through Albuquerque’s far northeast heights.

As long as it’s not raining, it’s a super safe route, because no cars!

It also came with fascinating side effect. Below grade, lined with neighborhood back fences, the ride deprived us of our usual geographical cues – as close to being “lost” as is possible in a city with a mountain looming to the east and a river to the west.

We emerged in a park at the arroyo’s uphill terminus, with a general sense of where we were, but only the vaguest of ideas as to the specifics. We have a “no iPhone maps” rule on our rides, so the only way to get our bearings was to keep riding.

It was delightful.

“To become completely lost,” Kevin Lynch wrote in his 1960 book The Image of the City, “is perhaps a rather rare experience for most people in the modern city.”

I ride a lot, and I map all my rides. I’ve done that for years, since the first affordable, portable bike-mounted GPS gizmos became available. I used to ride a bunch of favorite roads and trails over and over, but in recent years, I’ve used the technology and a couple of cool web tools to think about where I haven’t ridden yet.

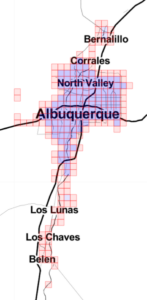

2021 Albuquerque tiles ridden

One game, which goes by the name “tiling”, divides the world up into mappable tiles – think an entire globe covered with bingo squares. It’s based on Ben Lowe’s Veloviewer, one of a number of great indy web-based software platforms for this kind of stuff. (See Ride Every Tile for a window into the strange and wonderful world of tiling – my obsession is modest compared with some of the European tilers.)

The other game, which I began playing this year, uses Craig Durkin’s Wandrer. Wandrer ingests all your old GPS rides and gives you a map of roads you haven’t ridden. You can even download a map onto your bike GPS gizmo to see streets around you as you’re out riding.

This leads to a lot of cul-de-sacs and resulting dog-related adventures.

I’ve always been a bit wandery in my riding, and Veloviewer and Wandrer provide a fascinating structure around the thing. I’ll often plan a ride with a vague goal of an unridden tile and a map of unridden roads in the area. But I rarely end up doing what I intended. And why not? It’s a bike ride!

This year I’ve ridden:

When I finally settled on setting the next book here in my “Middle Valley” rather than on the Lower Colorado River, one of the reasons on the “plus” side of the ledger was the ability to hop on my bike and ride to my “field area”. All this bike riding, what my friend Maria Lane labeled #geographybybike, involves the construction of intuitive maps of the landscape, hydrographic and human. The time from side yard bike shed to Rio Grande is 35 minutes – less if I need it.

Picking up new Veloviewer tiles and Wandrer miles creates a bit of a framework for expanding that mental map.

That’s true and all, but also maybe just a layer of excuse?

The neuroscientist and urbanist Robin Mazumder wrote a piece in 2019 that really captures why I ride. It’s about what psychologists call “flow”:

According to Jeanne Nakamura and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, flow involves the following elements:

- Merging of action and awareness

- Intense and focused concentration on what one is doing in the present moment

- Loss of reflective self-consciousness

- A sense that one can control one’s actions; that is, a sense that one can in principle deal with the situation because one knows how to respond to whatever happens next

- Distortion of temporal experience (typically, a sense that time has passed faster than normal)

- Experience of the activity as intrinsically rewarding, such that often the end goal is just an excuse for the process.

It’s not uncommon for me to return from a ride and have Lissa say, “You were gone a long time!” And I know that I was, because I have a watch and a phone and a GPS gizmo that all have been telling me this the whole time, and as a safety measure I’m always attentive to keeping Lissa posted on when she should expect my return.

But it doesn’t feel like a long time. The unfolding of a bike ride, the endless series of decisions (“What happens if I turn here?”), a gloriously unplanned “loss of reflective self-consciousness”.

When I started to write this post, I had a vague destination in mind, involving our mental maps and the benefit cycling provides to mine.

As often happens, that’s not quite where I ended up.

fallowed vineyard, Albuquerque, New Mexico, December 2021

My newest hobby – running down the water story for random patches of Albuquerque.

From Sunday’s bike ride, a fallowed vineyard, a bit more than an acre in size.

It’s at the base of the sand hills on the east side of the Rio Grande Valley, just down the hill from a Ford dealer.

Per OpenET, it hasn’t been irrigated since at least 2016 (that’s as far back as I can look currently).

Doesn’t look like it has access to ditch water (it’s uphill from the closest irrigation, the Alameda Lateral). The nearest well is a state-approved yard well across the street, drilled in 1967.

Healthy crop of tumbleweeds this year. Per county assessor records, that seems to have been sufficient to claim agricultural property tax break.

But here’s the best part:

The three closest streets are named “Vineyard”, “Muscatel”, and “Tokay” (an Anglicization of “Tokaji” – wines from a region called Tokaj in Hungary and Slovakia).

Clearly, further research needed.

Lissa, an able book research field assistant (by which I mean she happily listens to my yammering, asks the best questions, and indulges the vital forays into the field to see stuff), joined me on a drive yesterday afternoon to the Barelas Bridge, one of seven Rio Grande crossings in the river’s Albuquerque reach.

There’s an odd little cluster of buildings on the bridge’s west end that look a little bit like an old roadside motel, but older and smaller and somehow more puzzling. Also, now, boarded up.

1931 Sanborn map of west end of Barelas Bridge, courtesy Library of Congress

The 1931 Sanborn map of Albuquerque (am I the only one who spends evenings lost in the Library of Congress collection of Sanborns?) describes it as a “tourist camp”. They began sprouting up along the nation’s developing network of “highways”, as auto tourists began spreading out across the country. I first ran across a reference to them in a lovely little bit of work by Van Citters Historic Preservation, a review of the area done as part of a Bernalillo County public works project:

[I]n the mid-1920s, as automobiles became more accessible to the American public and recreational travel grew, many small, private, locally owned “tourist camps” were being built on US 85 and 66 both on the outskirts of Albuquerque and along those corridors within town. Tourist camps typically a collection of stand-alone structures or rooms that would be rented for the night and often had communal bathrooms and kitchens (although the earliest tourist camps consisted of actual camp sites in public parks). Over time they became known as “tourist courts,” and after World War II they were typically under a single roof and began to look more like modern motels. In general, these camps operated well into the 1960s. They provided an increasing array of amenities, such as heat, electric fans, and private bathrooms and kitchens.

In 1931, the Sanborn maps identify six of them along the streets that made up the western approach to the Barelas Bridge, along with filling stations and an auto repair shop. By the 1940s, they dominated the area’s streetscape economy.

I’m down this rabbit hole because, for the new book, Bob Berrens and I are trying to run make sense of how Albuquerque as a community solved the many collective action problems posed by living on the floor of a river valley. Nothing unique to Albuquerque. To quote Steven Solomon:

How societies respond to the challenges presented by the changing hydraulic conditions of its environment using the technological and organizational tools of its times is quite simply, one of the central motive forces of history.

We’re mostly thinking about the challenges around that time period posed by the need for flood control and drainage, and to a lesser extent irrigation. Those will almost certainly be the primary focus of the book. But bridges! Such a fascinating collective action problem, in the time when the whole idea of collective governance at the city scale was being invented.

Barelas was an oft-used ford across the river until 1898, when the first bridge was built.

The 1908 Sanborn map of Albuquerque includes what at the time was the major Albuquerque crossing of the Rio Grande in the Albuquerque reach, simply labeled “County Bridge”.

It connected the villages of Atrisco on the river’s west side to the city’s downtown and, importantly, the yards of the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad – the valley’s major employment center.

Santa Fe New Mexican, Sept. 5, 1907

At that time it was mostly wagons that used the bridge – and sheep – Bob found the excerpted newspaper story to the right, from the Santa Fe New Mexican. 23,500 sheep! (Lissa: “I wonder how many dogs that took.”)

But as the newspaper coverage of a 1912 washout made clear, the Barelas Bridge was a vital piece of community infrastructure.

The County Commission gave Herculano Garcia permission to operate a temporary ferry under the condition that he not charge more than 5 cents per passenger.

Alfalfa crops on the west side of the river sat, “spoiling on the ground” (ABQ Morning Journal, June 28, 1912) unable to get to market.

But most importantly, perhaps, for the city’s economy, railroad workers who lived on the Atrisco side of the river couldn’t get to work.

The back-and-forth over fixing the bridge, as with much of what was going on in Albuquerque at the time, suggests that providing the infrastructure needed for a growing city was the core collective action problem the community faced.

I’m still sorting out what happened next, but I think we’ve got a classic case here of other people’s money. It’s a theme in all these stories – as with much of the developing West, Albuquerque never quite could afford the stuff we needed to graduate to city-ness, so we turned to the federal treasury for help. More work needed here, but I think the key is the 1916 Federal Aid Post Road Act, which provided federal matching money for stuff like highways and bridges.

Not sure where all of this goes. I remain fascinated by bridges as an example of collective action problem-solving, though it’s orthogonal to the main “drainage and flood control and sorta irrigation a little bit” theme of the book.

Lake Mead, December 2021, by John Fleck

In the wake of a Colorado River Water Users Association meeting that was by turns exuberant (We got to see one another for the first time since the Before Times!) and stark (The reservoirs are nearly empty!), Anne Castle and I have a new paper out this week in a special issue of the journal Water with some suggestions for what needs to happen next.

Our key bits:

Our conclusion:

The past three decades of Colorado River basin-scale water management resemble the children’s game of “Red Light-Green Light.” When the child designated as the “traffic light” calls out “green light,” competitors are permitted to run forward toward the finish line. When the traffic light calls out “red light,” they must stop. Anyone who does not stop in time is sent back to the start.

In the Colorado River Basin, climate has played the role of a traffic light. When it delivers dry years, rapidly dropping reservoirs create a “green light” condition in which attention and concern may shift the river’s management from a condition to be monitored to a problem to be solved. The “red light” turns back on when a good snowpack delivers above-average flows to the reservoirs and refills depleted storage. The river game’s “green lights” and “red lights” create a classic opening and closing policy window, as described by Kingdon.

This phenomenon can be seen most clearly in the transition from inaction in the 1990s to action in the early 2000s. The river’s policy management community, fully aware of the possibility of future difficulties, discussed a range of potential policy actions to respond. However, full reservoirs created a “red light” condition. As the reservoirs dropped in the early 2000s, the light flashed “green,” a federal mandate was issued, and important, difficult policy steps were taken.

The hydrologic conditions of 2020 and 2021, together with dwindling water storage reserves, create a “green light” opportunity. However, unlike the common traffic signal, the green lights are brief when compared to the time requirements of negotiation. A favorable water year or changes in river decision makers could cause the light to suddenly turn red. State and federal water officials should seize this opening, cognizant of its likely limited duration, and cement new agreements that steer river operations in a more sustainable direction. Well-timed and explicit federal direction may be necessary to catalyze the already ongoing discussions. Failing to capitalize on the green light now means even more depleted reservoirs and a narrowing of available options for the future.

A huge thanks to Brian Richter for inviting our contribution to Water’s special issue on Advances in Water Scarcity and Conservation.

The paper is Fleck, J.; Castle, A. Green Light for Adaptive Policies on the Colorado River. Water 2022, 14, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14010002