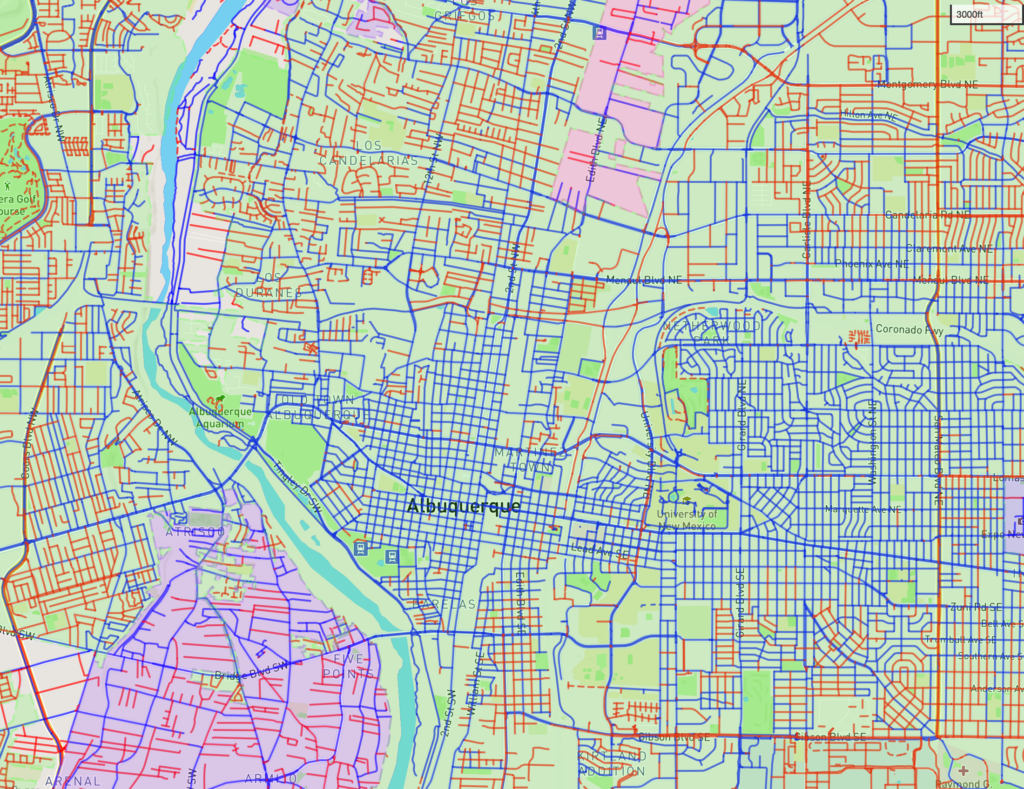

Red – the roads not yet ridden, courtesy Wandrer

“Well, you have your compost!” – L. Heineman

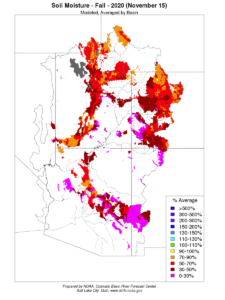

We got 5.88 inches of rain this year at the “official” Albuquerque airport weather station, which for perspective is essentially a one-in-six dry year based on over a century of records. But we got 7.05 inches at our house. Plus, as Lissa pointed out, I have my compost.

Yes, my compost. This morning I found a plate of peels Lissa had lovingly preserved from her evening tangerine snack.

Treasure!

It has become a neighborhood project. I converted an old stock tank we’d been using as a pond, and my neighbors Alison and Larry contributed a compost tumbler they weren’t using and bags of leaves (“We’ll leave them under the trees on the south side of the yard if you want any,” Alison texted. Of course I wanted them.)

Leaves go in the tank, and after a starter of leaves the tumbler gets the kitchen scraps (the better to protect them from what might be a backyard squirrel, lurking in the night).

After twirling the tumbler, I always peer in and take stock of the little crawly things doing their compost duties, a tiny ecosystem, a little miracle. The life force, an old friend once told me with a tone of Catholic reverence, is strong.

As you know, some bad stuff happened in 2020. I’ve got nothing much to add there, beyond the fact that Mom didn’t die. “There are things which are within our power,” Epictetus wrote, “and things which are beyond our power.”

Kewa Station, March 1, 2020

In retrospect, I can see the collapse already beginning in March, when my friend Scot and I rode the Railrunner, New Mexico’s commuter train, up to the Kewa station two thirds of the way to Santa Fe, with our bikes. We’ve an informal rule that we don’t put our bikes in a car and drive to a place to ride – gotta ride out the door. But we’d been experimenting with public transportation as a range extender – first Albuquerque city buses, then the train.

Scot’s a bike touring veteran, but the 50 miles back from Kewa (plus the 4 1/2 from my house to the station to catch the train) had been a stretch goal for me.

I don’t specifically remember tumbleweeds, but the station had a tumbleweed-blowing-across-the-highway western movie feel. Train pulled off, lone auto picking up a rider pulled away, and we had the whole place to ourselves – colonizers on Kewa land.

There was a stop at the irrigation diversion dam at Angostura, and this being the Time Before there was a taco stop in Bernalillo. It would be another two weeks before last tacos – two weeks etched in memory – a crazy quick weekend at Hoover Dam to film a documentary, that last Thursday meeting with my students, the awkward start of a spring break that never ended, melting into one endless Zoom class.

The thing within my power

In the manner of Epictetus, the bike has become the thing within my power, and I have in response ridden it a lot.

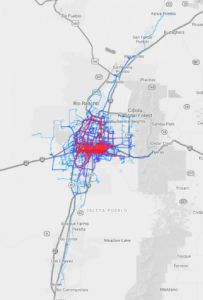

As I have written before, I’m no longer zoomy. At 61 years of age, I ride now for place – #geographybybike, as my friend Maria Lane (an actual geographer) dubbed it. This year that has been 6,396 miles, slowly, an hour-and-a-half a day on average, almost entirely in and around Albuquerque. That is, for me, a crazy lot of miles, far more than I’ve ever ridden in a year.

Early on, as the pandemic shrank my world, the riding was frenetic. With so little within my control, I obsessed over the tools I needed to mount more water bottle cages on my bike, poring over the maps and my old GPS ride archives in search of the places I had not been. Epictetus overkill. With the taco truck option epidemiologically foreclosed, I’d coordinate with Lissa to make her magical quesadillas, looping home for a lunch break before heading back out for more miles. That compressed the geography further, kept me closer to home even for the longest of rides.

Closer to home, a comfortable tether.

By summer the frenzy had calmed, and I settled into a rhythm – ride most very day, with a not-quite-so-long Sunday ride, a tentative return to riding with Scot and lunching at the taco trucks.

This fall I discovered the wonderful Wandrer, a tool that allows you to upload all your old GPS traces, building a map of the roads you haven’t yet ridden. I’ve GPS’ed every ride since 2007-08-ish, and was delighted to find all the roads yet to ride.

I have, in other words, found a comfort in the things within my power – lines on a map which only I can draw, one pedal stroke at a time. Compost in the garden.

I didn’t mean to write a blog post about bicycling. As I start to work on a new book, I’ve offered my collaborator, by way of explanation of process, what has long been an amazingly useful metaphor:

You’re standing at the edge of a mountain stream, too wide to jump, too cold to comfortably wade. It’s strewn with rocks, and you start across, one rock at a time, hoping you can imagine a route a few hops ahead, but unsure of the exact path. That’s the way writing is for me, mostly joy, sometimes I fall in and get really cold and wet.

I started today with my morning weather data, then Lissa suggested compost. So I hopped onto the first rock, then, the second.

2020 bike riding had been in the back of my mind – or to follow the metaphor, a jumble of rocks midstream. Epictetus has been a handy rock since the first time I read him 40 years ago. (I was surprised to run a search and find I’ve never used him before.) There’s a pile of rocks over to the left that you may read about eventually, involving Lake Mead’s elevation and total Lower Colorado River Basin water use, etc. Another pile to the right that involves path dependence and the institutions of water management. Not touching that one – I’m sure to fall in.

Census of Agriculture

Metaphors do the most useful work as they are breaking down. The stones aren’t so much laid out in the stream in front of you – they’re things you find, tossing them ahead to make it easier to cross the stream.

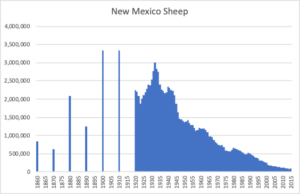

As near as we can see the path across the stream at this point, the new book will be about the Rio Grande and the making of modern Albuquerque. It’ll probably talk about sheep, and a remarkable guy named Max.

I’ll be finishing my time as University of New Mexico Water Resources Program director this summer, to free up more time for said book. I hope to still have a role at the university, working with water students and faculty, perhaps teaching, and wandering ’round the Duck Pond on sunny post-pandemic afternoons. (Plus I’m writing a book, university library privileges, amiright?)

And Scot and I have already been poring over the maps for tomorrow’s New Year’s Day ride, new lines on a blank 2021.

No taco trucks, but Lissa made oatmeal cookies.

2020 in a nutshell (I did at one point, when the weather was warm, figure out how to mount four water bottles on the frame)