Cities.

Farms.

The natural environment.

All of it.

We can do it in an orderly way, or devolve into chaos.

That’s it. That’s the blog post.

Cities.

Farms.

The natural environment.

All of it.

We can do it in an orderly way, or devolve into chaos.

That’s it. That’s the blog post.

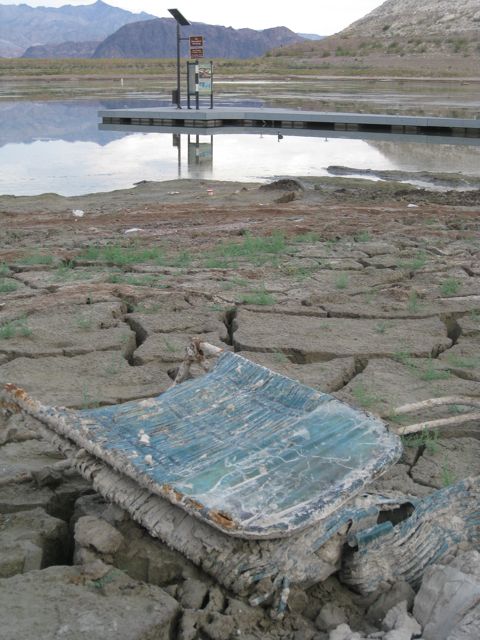

Cracked mud at Boulder Harbor, Lake Mead, Oct. 18, 2010

It has become a Frequently Asked Question of late here at Inkstain World Headquarters:

John, you’ve frequently been quoted in the past expressing optimism about the future of the Colorado River Basin.

Dude, Lake Mead is so low they’re finding dead bodies.

Are you still optimistic?

My answer, of course, is “yes”.

It’s in my contract.

“the harbinger of doom”

Some years ago, I wrote a book called Water is For Fighting Over (and Other Myths About Water in the West). It hasn’t made me a whole lot of money, but it was generally well received. The New York Times called it “illuminating“, and radio talk show host Ross Kaminsky called it “fascinating”.

In it, I laid out a novel argument: Despite the water management and development mistakes of the past – overbuilding our cities and farms in the desert, in the process growing increasingly dependent on an increasingly unreliable water supply – we aren’t screwed.

Why?

I laid out what I and most of my family members agreed was a fairly compelling case about successful water use reductions and collaborative governance that, I argued, have created a framework for sharing rather than fighting over water.

It was a defense of the adaptive capacity of human communities. “When people have less water,” I wrote, “they use less water.”

When WIFFO came out in 2016, it was a bit of a novelty. “Hey, there’s this guy Fleck who doesn’t think we’re screwed! Let’s invite him to come speak at our conference!”

There I would be, in some hotel conference room in Las Vegas (it always seemed to be Las Vegas) offering up my charts and graphs of water conservation success, and stories about people coming together like happy kids on the elementary school playground whose moms had packed yummy treats in their lunchboxes. Treat shortage? No problem, we’ll share what we’ve got before we head out to play Foursquare.

I’d make self-deprecating jokes about my old newspaper self hunting up pictures of cracked mud for my drought stories, grabbing the front page by ominously hinting at our impending doom. (True story: One of my editors used to delight in calling me “the harbinger of doom”, a golden ticket to the front page.)

And then one of those annoying climate scientists would get up (it always seemed to be Brad Udall) with their charts and their graphs about long tail risks of rapidly declining river flows. It was an exercise in uncertainty – climate change my be this bad or it might be that bad. And I would bury my head in my hands. Some climate change, some reduction in river flows, I would think to myself. We can handle that with the tools I had just described. But out toward the scary edge of Brad’s graphs?

I could see how climate change could outpace the tools I had described. Out there, we’d be screwed.

In 2016, when WIFFO came out, the combined storage of Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the two primary water supply reservoirs on the Colorado River, was about 22.4 million acre feet. At the end of this water year, it’s projected to be down to about 13.1 million acre feet.

That’s a decline, on average, of 1.5 million acre feet per year.

For the six years I’ve been out on the hustings hawking my book and its optimistic message, we’ve been using, on average, 1.5 million acre feet more per year than the river has provided.

1.5 million acre feet per year is six Las Vegases. It’s 30 Albuquerques. It’s more than half the farming in the entire Imperial Valley, year after year after year.

If I was my critic, I’d have to point out that dude, Lake Mead is so low they’re finding dead bodies.

It’s a fair cop.

One of my favorite lines in Water is For Fighting Over isn’t mine. It came from my beloved editor Emily Turner, to whom I owe so much, and landed in the last paragraph of the book.

I was talking about the risk of headlines of doom. Emily was the one who, riffing off of the “not really something Mark Twain said” theme of the book’s title, found the bolded bit below:

[I]f you are able to sidestep the crisis narrative and recognize that your community can thrive with less water, then the fight with your neighbors seems less necessary and the risks of water wars and a crash diminish. It’s time to stop fighting over water and turn our attention to another adage Mark Twain likely never said: “The secret of getting ahead is getting started.” When we start talking, we can learn to share our beloved but dwindling Colorado River in a changing world.

This is the heart of the thing I didn’t understand when I wrote that book. “Getting started” is harder than I thought.

“Getting started” is a weird way of thinking about this, because the body of that book, all 250 pages of it, is a whole bunch of very successful work done in the two previous decades to conserve and share water. But next steps are always harder than the last, and they’re hardest when the reservoirs still have water in them.

That’s the thing about the six years since Water is For Fighting Over came out. For the first four of those six years, the reservoirs were relatively stable – two up years, two down years, leaving them basically where they were when I first sat in those Brad Udall talks with my head in my hands. The reservoirs weren’t inexorably dropping.

Basically the entire drop in the system that is now revealing Lake Mead’s dead bodies has happened in just two years.

We could wish that it wasn’t so hard for water managers to tell their users, “Y’all need to fallow those fields and tear out those lawns now because things might be bad in future years.” We all wish now that we had done stuff like that five years ago and built a buffer so that when the bottom dropped out of the system in 2021 we had a bit more of a cushion.

But we also could wish that carbon emissions didn’t warm the atmosphere. Both seem to be boundary conditions here, and wishing human politics and human nature were different than they are seems no more helpful as a policy recommendation than wishing that greenhouse gases weren’t fucking everything up so badly. That’s the reality we need to start from.

Sorry, dear readers, this post is already far too long. But it’s my blog.

I’m trying to think through a talk I’ve been asked to give next week to a bunch of Colorado River people at the Law of the River CLE in Santa Fe – looking forward, where do we go from here, what does the next hundred years of the Compact hold for us, etc. The reality of my forty years as a writer of newspapers and other things (eek I am old!) is that I a) don’t know what I think about something, really, until I try to write it, and b) the writing doesn’t really work unless it’s done in public.

I’ve never been one for journaling. So thanks for hanging in, dear readers.

The wisecracking schtick at the top, before I shifted to my ominous Rod Serling voice, included my joke about how it’s my job to be optimistic, that it’s in my contract.

I have no contract. I made that up.

But despite all the Sturm und Drang, I am optimistic. Because the tools are all there. All the things I wrote about in Water is For Fighting Over can be scaled up when they have to be. It would be nice if we’d scaled them up sooner, but now that we’re pretty much out of water, we’ll have to, and we will.

The most important and useful thing I’ve helped write recently was this paper with Anne Castle, where we drew on the academic literature of what I might call How Stuff Actually Gets Done, rather than the literature of How We Wish Stuff Got Done. We argued that the river’s current plight has opened a window of opportunity for strong actions that might not otherwise be possible.

The current state of dramatically decreased overall flows has opened a window of opportunity for the adoption of water management actions that move the river system toward sustainability.

In working on that paper with Anne, we tried to mindful of Bob Lalasz’s admonition to folks like us that “the times call for as much solution specificity as you can muster”. We did that – Colorado River water managers should check out the supplemental tables.

The solutions point in two directions – from the top down, and from the bottom up.

From the top down, rejiggering the river’s rules so that there is clarity about how much less we all need to use to bring the system to sustainability is the key. I’m not sure of the answer – do we need to cut 15 percent out of the system? 20? Do we need a system that’s more flexible and robust so we’re have a plan for whatever climate change throws at us. (My answer: yes.)

I’m confident that my friends at the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority, who so capably bring Colorado River water to my shower head each morning, would prefer not to have to cut a whole bunch more than we already have, and I’m also sure they have a pretty good legal argument about why the cuts shouldn’t fall on us.

But as I’ve written more than once, pretty much everyone is lawyered up with arguments about why the cuts should fall on those other people and not them. And there’s not enough water for all of the lawyers to be right.

And I also am confident that every single water user on the system, if forced to, could find a way to have a rich, vibrant community with less water than they’re using now.

Including me.

When people have less water, they use less water.

That’s why I’m optimistic. Somebody has to be. We have to model what success might look like.

Thanks for sticking with me, see y’all in Santa Fe next week.

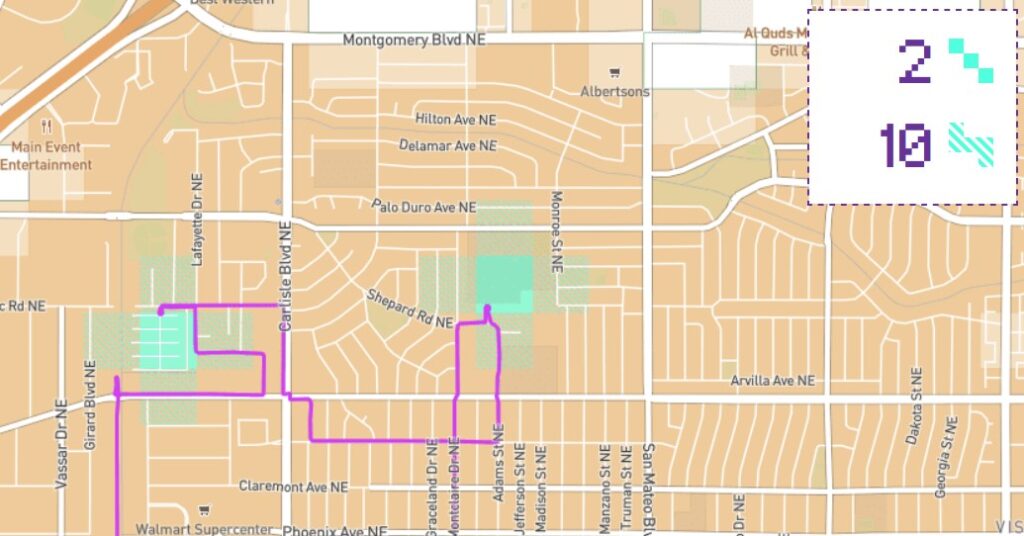

“numbers go up”, Squadrats version

I’m feeling old and tired, so Squadrats, a new (to me) GPS mappy bike game, arrived at a good time.

There’s a video game culture catch phrase, “numbers go up”, which describes the incentives designers have to give you ways to make some number go up, to lure/hook you into playing ever more. (Think “streaks” in Duolingo.)

For years, I’ve played such a game with my age, celebrating my birthday by riding said age in miles on a bike to celebrate. But this year, 63 became a beast.

The ride was epic. I did it early, feeling good on a random Sunday a few weeks before the big day, I showed up to the morning meetup for the weekly Sunday ride with my friend Scot and said, “I wanna do the birthday ride today.” We already had planned out a long ride, and Scot’s always up for long bike riding fun, so off we went. It had everything – dirt, levee roads, water management chaos, and tacos.

It was full of things going wrong – the least of which was a GPS bike computer crash, the greatest of which was an actual bike crash.

The bike crash happened at low speed, a wheel caught in a pavement crack on a little climb, and felt minor at the time. I got up, brushed off, rode a bit to see how I felt, which seemed OK. Scot and I went back and forth about options to get me to a nearby bus to get home, but I was having fun, dammit, and it was my birthday! So I rode on, another 25 miles to finish the 63. A little stitching together of a borrowed GPS track from Scot’s ride to overcome the GPS malfunction confirmed the 63-ness, and the numbers had gone up!

But nearly three weeks later, my rib cage still aches from landing hard.

I am old.

The “numbers go up thing” has always been part of the cycling game for me – miles, GPS tracks. It’s fun! I’ve never been particularly fast – during the years I raced bicycles I was arguable the slowest bike racer in Albuquerque. (I am neither particularly physically gifted, nor have I ever “trained” particularly hard.) The map games are a great alternative, incentivizing time on the bike and geographical exploration.

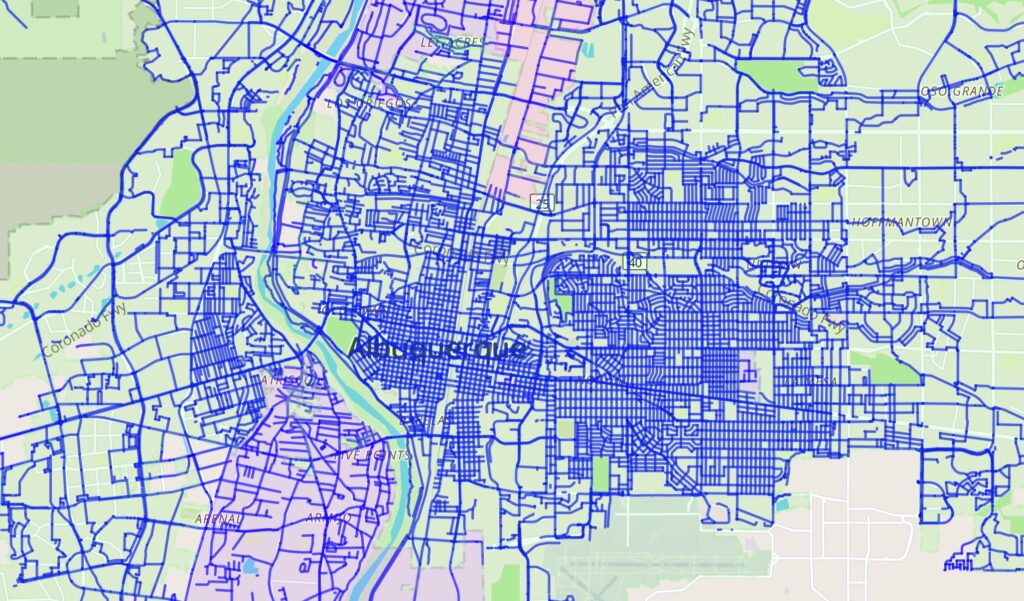

In blue, streets I have ridden in the central part of Albuquerque, courtesy Wandrer

I play Wandrer, which tracks unique streets, trails, etc., that I’ve ridden (I’ve ridden 1,821.5 miles of the 5,446 miles in Bernalillo County, where I live). But “tiling” is the most fun.

The game originated with a guy named Ben Lowe, a cyclist and software developer in the UK who runs the Veloviewer web site. As he explained in a 2016 post:

The VeloViewer Explorer Score and more specifically the Explorer Max Square has acquired a bit of a cult following since its introduction to the site back in March 2015 despite me not having fully explaining what it is all about until now! The Explorer Score rewards those people who explore new roads/trails rather doing the same old loops. Providing non-performance based motivations has always been one of the main goals of VeloViewer and this one really looks to tick that box.

That – “non-performance based motivations”, i.e., slow old person stuff – has John Fleck written all over it.

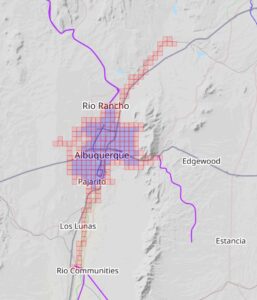

tiling Albuquerque – my 2020 pandemic riding map

I got hooked on tiling back in 2020, when pandemic riding became (?was it always?) a mental health anchor. That year, as you can see by the map, I basically covered all of Albuquerque, absent a single pesky square in the middle of Petroglyph National Monument, where cycling is prohibited. (I eventually hiked in this year to get it – any “activity” with a GPS track counts.)

The tiles are ~2/3 of a mile on a side, and you color one in by riding (or walking, hiking, running, whatever) through any bit of it with a GPS on.

Tiling has became a niche but epic game, especially popular among crazy long distance cyclists in Europe, where the density of the road network makes it possible to color in massive areas of one’s map if one has the time and legs.

But for aging me, the game was losing its luster because it was becoming increasingly difficult to get new squares on my lifetime map. You can see the way I worked up and down the Rio Grande back in 2020, and my current map covers the river all the way from near Cochiti in the north to well past Belen in the south. So getting more river squares has been a big part of the game. My “new bike” was basically set up for tiling, with tires that can run on dirt and a rack and bags to carry food for longer rides. But I’m old and slow and lazy, and each new square is increasingly difficult, requiring either very long rides, catching a bus or train to the start point, or throwing the bike in the car.

I hate throwing the bike in the car, much preferring “out the door” adventures.

Enter Squadrats.

bagging the Aztec Village mini-tile

With GPS units for riding super cheap these days, and the Strava platform’s API making it easy to upload and move your ride tracks about, the technology side makes it increasingly tractable both for riders and developers. Squadrats takes the game and breaks up each big Veloviewer tile into 8 mini-tiles. Suddenly I’m afforded with tons of opportunities to make my numbers go up on short rides by going back to little tiny chunks of Albuquerque I’ve missed. This morning I was feeling punky after getting my Covid booster shot, but still had the oomph for a short ride up to the Aztec Village mobile home park, where I’d determined that if I rode up to their security gate, I’d be barely inside one of the mini-tiles I’d missed.

The hook for me was this ride shared by Jonathan France, one of the crazy-wonderfulest European tilers, describing the work needed to get the mini-tile encompassed by Westfield Mall in London:

The Westfield mini-tile is easy to get into, but almost impossible to get a GPS signal in. The service roads and entrances on all sides let you get near but not in with a signal. I fudged it eventually by entering the car park and standing near a sky light long enough to get a signal.

France’s lifetime map is amazing. Here’s London, his home base. The dark orange bits are a densely connected network of mini-tiles (basically the largest collection of tiles that he’s ridden that are surrounded on all four sides by tiles that he’s also ridden – “clusters” in the Veloviewer lingo, or “Yardinhos” in Squadrats). Light orange are areas where he’s ridden some, but the network isn’t quite so dense, with holes scattered through it.

Jonathan France’s London tiling map

France is a bit of a role model for me – a guy in his 60s who likes to ride his bike, for a long time, slowly. The photo essays that accompany his rides are lovely (there’s a social media aspect of this). I’ve adopted his Strava tagline:

“seeking out the #SlowWays”

On my birthday ride, I got 25 new mini-tiles.

Ideas on Earth were badges of friendship or enmity. Their content did not matter. Friends agreed with friends, in order to express friendliness. Enemies disagreed with enemies, in order to express enmity.

Kilgore Trout, in Lingo-Three, as quoted in Vonnegut 1973

Armijo Acequia (AKA Ranchos de Atrisco Ditch). A functioning irrigation canal in the middle of Albuquerque which dates to the 1700s. Note batting cages at the upstream end of this stretch of ditch.

I love living in a town with a ditch bearing the name of co-workers.

I love living in a town with a ditch that’s been continuously, tenuously irrigating this land since the 1700s.

I love dodging traffic by turning down a “Dead End” street, knowing that only means cars, that bikes can pop out on the ditchbank and keep going.

I love the realization that this is the spot where the Armijo disappears under the Batter’s Edge batting cages.

I love living in a town where our embrace of modernity includes putting in a culvert so we can keep irrigating this rich, green, shaded landscape while also refining our baseball skills.

Get a load of that duck.

Important observation from Jack Schmidt, Utah State Colorado River guy, on the new constraints on Colorado River management as Lake Powell and Lake Mead drop:

“We’re in crisis management, and health and human safety issues, including production of hydropower, are taking precedence,” said Jack Schmidt, director of the center for Colorado River Studies at Utah State University. “Concepts like, ‘Are we going to get our water back’ just may not even be relevant anymore.”

Audubon’s Jennifer Pitt, one of the most stubbornly optimistic actors in the Colorado River Basin, wrote this Friday:

[F]ederal officials project that within two years, the water level in Lake Powell could be so low that it would be impossible for water to flow through the dam’s turbine intakes. When that happens, it’s clear the dam will no longer generate hydropower, but it’s also possible the dam will not release any water at all. That’s because the only other way for water to move through the dam when the water is low is a series of outlet tubes that were not designed, and have never been tested, for long-term use.

What happens if little to no water can be released from Lake Powell? Water supply risks multiply for everyone who uses water downstream. That includes residents of big cities like Las Vegas, Phoenix and Los Angeles, and farmers and ranchers in Arizona, California and Mexico who grow the majority of our nation’s winter produce, as well as numerous Native American tribes. Some of these water users have alternative supplies, but some—including Las Vegas residents, Colorado River tribes and most farmers—do not. Day Zero for these water users might not happen immediately as Lake Mead, the reservoir fed by Lake Powell still has some water in it. But without flows from upstream to replenish it, Lake Mead would also be at risk of no longer being able to release water.

There is also the river itself. Think of it—no water flowing through the Grand Canyon. No water flowing in the Colorado River for hundreds of miles downstream from Hoover Dam. That’s an ecological disaster in the making for 400 bird species and a multitude of other wildlife, exceeding the 20th century devastation of the Colorado River Delta.

Watching the back-and-forth among the U.S. Department of Interior and the seven Colorado River Basin States over Glen Canyon Dam operations over the last few months, I’d been thinking that we’ve dropped into an area where the rules developed in 2007, and tweaked in the years since, no longer apply.

In short, if we use the reservoir operating rules the states and federal government negotiated back in 2007 (tweaked more recently by the ill-named “Drought Contingency Plan”), we drive Lake Powell below the level at which Glen Canyon Dam can generate electricity. Our only choice is to throw out the rules.

But speaking on the sidelines of the Stegner Center Colorado River Compact symposium last month, one of the smartest Colorado River lawyers I know corrected me. Because the rules were written in way that leaves Interior with an escape hatch. It’s Section 7.D of the Interim Guidelines:

The Secretary will base annual determinations regarding the operations of Lake Powell and Lake Mead on these Guidelines unless extraordinary circumstances arise. Such circumstances could include operations that are prudent or necessary for safety of dams, public health and safety, other emergency situations, or other unanticipated or unforeseen activities arising from actual operating experience. (emphasis added)

I still think my earlier observation has an element of truth. The decline in reservoir levels has dropped us into an area where the rules that were developed – a complex nested set of “if this, then that” rules where the this’s and that’s refer to elevations in Lake Powell and Lake Mead and annual releases from upstream to downstream – no longer work. By invoking the “extraordinary circumstances” clause – as Assistant Secretary Tanya Trujillo did in her April 8 letter to the states, and as the states did today in their letter written in response – the parties are agreeing to suspend the if-then’s and improvise.

But the ever-clever drafters clearly new bad shit was possible, and they were ready with the “extraordinary circumstances” clause.

I retain my admiration for the collaborative process of the seven states and Reclamation here. Holding everyone together for this rapid-fire reservoir management improvisational octet has been a truly impressive feat.

But given what has transpired, it’s worth looking back to the original purpose and need of the 2007 guidelines. In the supporting documents developed for the ’07 guidelines, Reclamation explained their purpose thus:

This action is proposed in order to provide a greater degree of certainty to United States Colorado River water users and managers of the Colorado River Basin by providing detailed, and objective guidelines for the operations of Lake Powell and Lake Mead….

“Greater degree of certainty”? In 2022, 15 years later, not so much.

At this point, no one knows what the fuck happens next.

For years, the Colorado River management community has ignored, or at the very least sidestepped, a problem that has effectively sent more Upper Basin water downstream to help fill Lake Mead. But with the reservoir system operating on razor-thin margins, this “bonus water” – seeping through the sandstone cliffs of Glen Canyon, rather than being released through Glen Canyon Dam’s penstocks – could become a significant issue soon.

That leakage adds up. 150,00 acre feet per year is 1.5 million acre feet every ten years – enough, had it not been sent downstream to Lake Mead, to have pushed the Lower Colorado River Basin into shortage four or five years ago.

On April 8th, Assistant Secretary Trujillo formally informed the Colorado River Basin States that the Bureau of Reclamation would like to make a mid-year correction to the operation of Glen Canyon Dam, reducing this year’s annual release from 7.48 maf to 7.0 maf. This action coupled with additional releases from upstream reservoirs is deemed necessary to help prevent Lake Powell from falling below the minimum power elevation. Clearly, if aridification continues, more proactive measures will be needed including revisiting the issue of how annual releases are managed considering what basin insiders refer to as the Lower Basin “bonus water”.

The 2007 Interim Guidelines include storage tiers that are used to set and adjust the annual releases from Glen Canyon Dam. These annual releases, however, are not the same as the flows at Lee Ferry, the compact point. There are two sources of water between the dam and Lee Ferry; the Paria River which has an average annual flow of 20,000 af/year and groundwater inflows below the dam which, since 2010, have averaged about 150,000 af/year. The negotiators of the 2007 Interim Guidelines considered the Paria (this is the reason the flow levels are 7.48 and 8.23, not 7.5 and 8.25), but did not consider the groundwater inflows for the simple reasons that the data were not then available and there had always been an assumption beginning with the promulgation of the first Long-Range Operating Criteria in 1970 that releases from the dam and the flow at the Lees Ferry gage would be the same. Former UCRC Executive Director Don Ostler coined the term Lower Basin “bonus water” to label these groundwater flows.

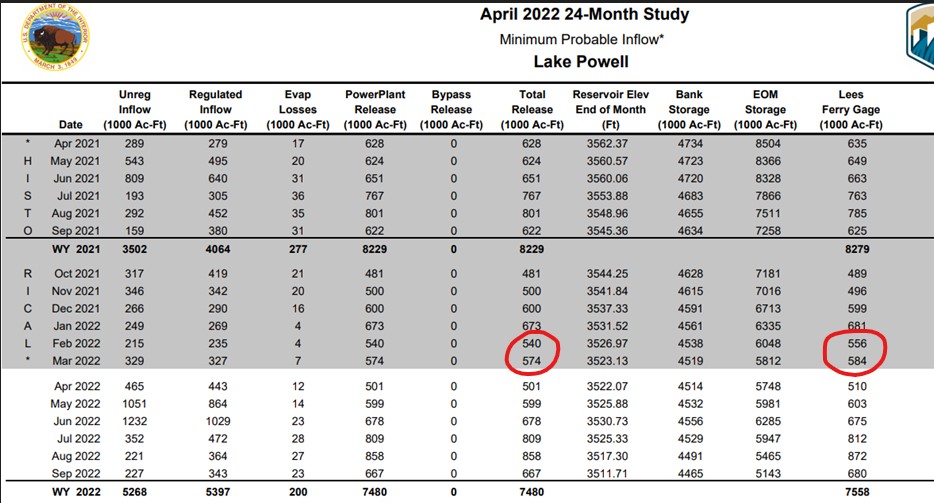

The 24-month studies show both the monthly releases from Glen Canyon Dam and the monthly flow at the Lees Ferry gage (about 1.5 miles upstream of the Lee Ferry compact point). Shown below is an excerpt from the April 2022 24-month study:

“Bonus Water” flowing past Lee’s Ferry

I’ve highlighted the total releases from Glen Canyon and the Lees Ferry gage flows for February and March 2022. In February the flow at the gage was 16 kaf greater than the release from the dam. In March the difference was 10 kaf. If one checks the 24-month studies back to 2010, the average annual difference between the gage and the dam release is nearly 151 kaf.

The annual amounts of bonus water vary considerably from month to month and year to year. There is a weak correlation between the annual regulated inflow to Lake Powell and the annual amount of the bonus flows and the monthly flows show a seasonal pattern, monthly bonus flows are the highest in mid-summer and lowest in late fall.[1] In 2019, the last wet year, the bonus flow was 270 kaf. For the 2021 drought year it was only 50 kaf. While 150 kaf/year may only be a small fraction (1.8%) of the normal annual release of 8.23 maf/year, over ten years it’s a big deal, 1.5 maf is over three times the 480 kaf reduction ordered by Assistant Secretary Trujillo. Had this 1.5 maf stayed in Lake Powell, its storage elevation today might be 20-25’ higher.[2] Further had it not been delivered to Lake Mead, a Tier I shortage may have been necessary 4-5 years ago forcing the Lower Basin to further ramp up their conservation efforts much earlier.

After the 2012/13 two-year drought, Ostler raised the issue of the groundwater bonus flows with technical representatives from the USGS, Reclamation, and the other states. The USGS looked at the gage issues and concluded that while not perfect, the accuracy of the Lees Ferry River gage and the ultrasonic flow meters used at the dam are state of the art. The bonus flows are not an artifact of gaging error. Further, a visual inspection of the river below the dam showed numerous springs and weeps. Despite these finding, there was little interest by the Lower Basin States or Reclamation representatives for using the Lees Ferry gage to manage monthly releases from Glen Canyon Dam.

The movement of reservoir water into bank storage, through the sandstone then back into the river below the dam is obviously a very complicated hydrogeology problem. Factors include the hydraulic conductivity and fracturing of the rock surrounding the dam and reservoir (mainly Navajo Sandstone), the storage level in the reservoir, whether the reservoir is filling or draining, and others such as local precipitation. We may not understand the fine details of how the groundwater gets to the river below the dam or how much of it originated from the reservoir. But what we know with certainty is that the water is in the river at the Lees Ferry gage – the Compact measurement point – and it is flowing downstream to the Lower Basin.

While the easiest path forward may simply be to wait and address this matter as a part of the renegotiations of the 2007 Interim Guidelines, why wait four years (or more if the current package of Interim Guidelines and DCPs is temporarily extended)? The Secretary has the authority to operate Glen Canyon Dam to meet an annual target flow at the downstream Lees Ferry gage. Unless we get an unusual series of wet years, refilling Lake Powell and the upstream CRSP reservoirs is going to be a struggle. Using this approach could keep an extra 600 kaf in Lake Powell over the next four years. It’s more water than what might be squeezed out of Blue Mesa and Navajo Reservoirs under drought operations.

It won’t solve the basin’s basic math problem. Only a reduction in total demand to match the available supply will do that. But it will better balance the burden on each basin.

[1] Based on the 12-year period of 2010-2021, average monthly bonus flows are the highest in August at 23.8 kaf and lowest in November at 4.9 kaf. The correlation between annual regulated inflows and annual bonus flows (WY) has an R squared of .59 which is significant at the P<.05 level.

[2] This is actually a much more complicated question. Under the 2007 IG tier structure, as my colleague Ben Harding has concluded, Lake Powell storage has “memory,” Changes in storage in one year carry forward and impact future years. For example, in both 2020 and 2021 Lake Powell was in the Upper Elevation Balancing tier. The releases were 8.23 maf, but had there been more water in Powell, they could have been as high as 9.0 maf depending on the storage level in Lake Mead.

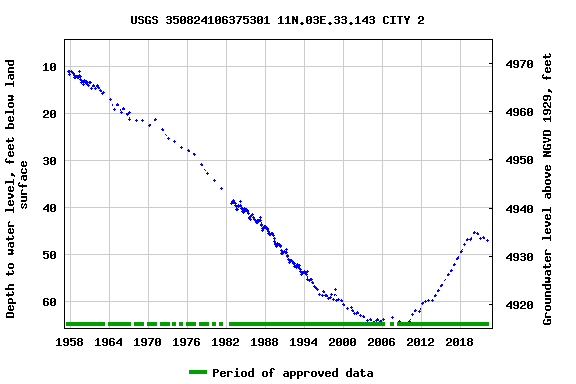

Losing groundwater in Albuquerque

At the eastern end of Sandia Road NW in Albuquerque is a ratty but important piece of Albuquerque’s water management history – City Well #2. Maintained now by the US Geological Survey, City #2 was installed in the late 1950s, a pivotal time in Albuquerque water management.

The community’s population was booming. To meet the new demand, the city’s water department was drilling groundwater wells all over town. Newly appointed State Engineer Steve Reynolds saw a problem, and was trying to put a lid on expanding groundwater depletions by requiring the city to offset any future impacts of pumping by retiring surface water rights.

Litigation shenanigans ensued.

City Well #2, with couch, photo by John Fleck, November 2020

Four groundwater wells were drilled in the summer of 1957 to begin monitoring what the heck was going on beneath the ground – a novel water management approach in the go-go years of the 1950s, when population all over the West was growing rapidly and communities were sinking groundwater wells with reckless abandon.

We’ve been monitoring the four wells – by Los Poblanos Open Space, in Los Duranes, by the tracks near downtown, and this one on Sandia NW – ever since, with the faithful USGS technicians making two measurements a year, early spring and late summer. It’s a wonderful dataset, telling a rich story.

When I first visited City #2 in the winter of 2020, it was flanked by a trash bin and an old discarded couch.

It also was beginning to show the effects of lower river flows.

The impact is largely indirect. When the Rio Grande is down, Albuquerque shuts down its San Juan-Chama diversions, pumping groundwater to meet municipal needs. We’ve been doing that for the last copuple of years, and you can see the impact in the graph above. After a steady rebound of more than a decade, our aquifer has begun dropping again. Whether this is an ominous sign of trouble ahead, or simply The Plan – use the aquifer as a drought reserve in times like this – is a point of debate. (I tend to come down on the side of the latter, notorious optimist that I am.)

Google streetview suggests the couch has since been removed, which I guess can be counted as progress.