The Chamisal Lateral, a shady oasis in Los Ranchos de Albuquerque.

In a sad but important way, the disastrous 2022 water year has been a gift to the writer, and I’m spending as much time as I can in reporter mode, sussing out the stories of this remarkable year.

In the new book we’re writing, Bob Berrens and I are trying to make sense of the decisions Albuquerque has made over the last century to live on the Rio Grande Valley floor – we shape river, and the river shapes us.

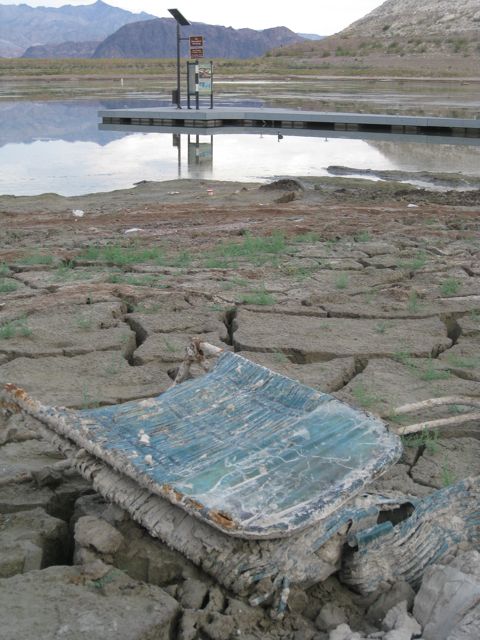

2022 is a test. There is less water, a lot less. What will we do? What will this place look like as climate change makes years like this less exception and more norm?

This morning’s bike ride took me through the middle of my hypothesis, a transect across the hydrogeography of Albuquerque – up the river valley through the community of Los Ranchos de Albuquerque, then out onto the riverside trails.

Los Ranchos was leafy and green. The riverside woods were parched, and the river itself, the part flowing between the levees, is at the lowest it’s been at this point in the year since 1989.

For those alarmed by the dropping river, and perhaps struck by the contrast with the buccolic, tree-lined Chamisal Lateral in the picture above, it’s worth considering why things are this way. Because it occurred to me as I enjoyed the shady lanes of Los Ranchos and then looked on at the dull agony of a drying river that this system is, in fact, working as designed.

We have a set of rules, encoded in state legislation and state and county implementation policy and therefore (I guess?) reflective of our collective values as a community that are designed to keep Los Ranchos green while allowing the river to go dry.

Rules as Water Management Design Principles Case 1: Domestic Wells

In 1953, the New Mexico legislature passed its first domestic well statute:

By reason of the varying amounts and time such water is used and the relatively small amounts of water consumed in the watering of livestock, in irrigation of not to exceed one [1] acre of noncommercial trees, lawn or garden; in household or other domestic use, … the state engineer shall issue a permit to the applicant to so use the waters applied for.

The statute has changed over the years a bit, but its basic principle still applies. If you want to drill a domestic well at your house, you get to.

The New Mexico Office of the State Engineer does have the authority to declare something called a Domestic Well Management Area “when hydrologic conditions require added protections to prevent impairment to valid, existing surface water rights”, but that has not been done here. (Source, p. 33)

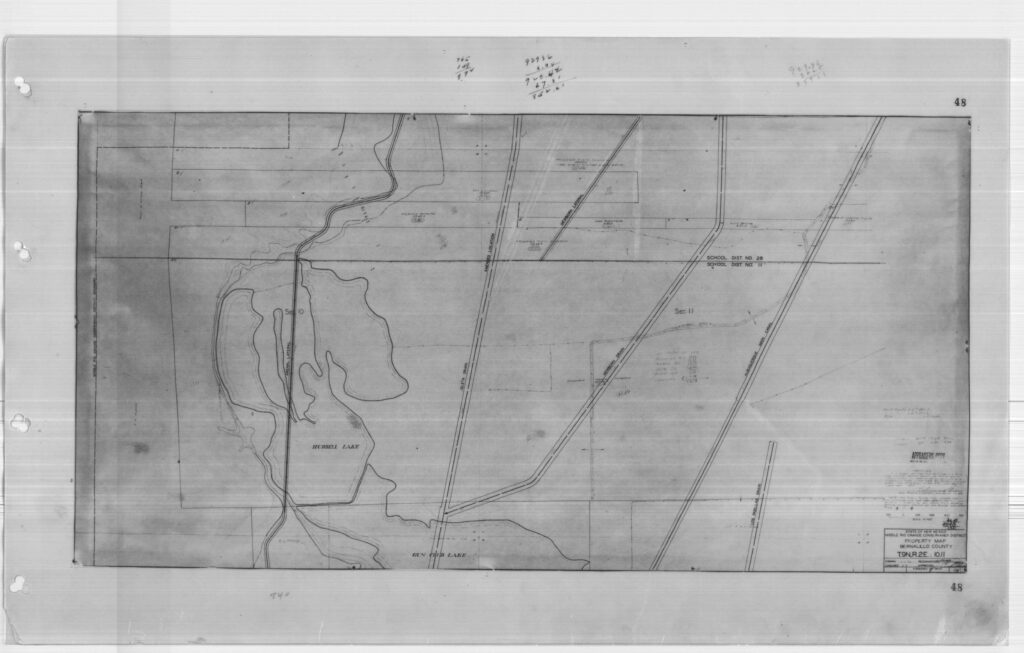

The result is a valley floor pockmarked with domestic well permits, allowing people to use water from the Albuquerque Bernalillo County Water Utility Authority for indoor use, and water their lovely yards from a shallow domestic well. But remember, those shallow aquifers are in direct connection with the river. This is basically water coming straight out of the river.

If our rules are a codification of our values and intentions, it seems here that our intention is to keep the valley floor green in times of drought. If it isn’t, we need to change the rules.

Rules as Water Management Design Principles Case 2: The Agricultural Tax Break

Our crazy smart UNM Water Resources Program student Annalise Porter recently finished a relevant piece of work on the agricultural property tax break irrigators get on the valley floor here in the greater Albuquerque metro area. Annalise defended in the spring, and is writing an expanded version of the project for a paper for publication. Soon! I think it’s really important stuff.

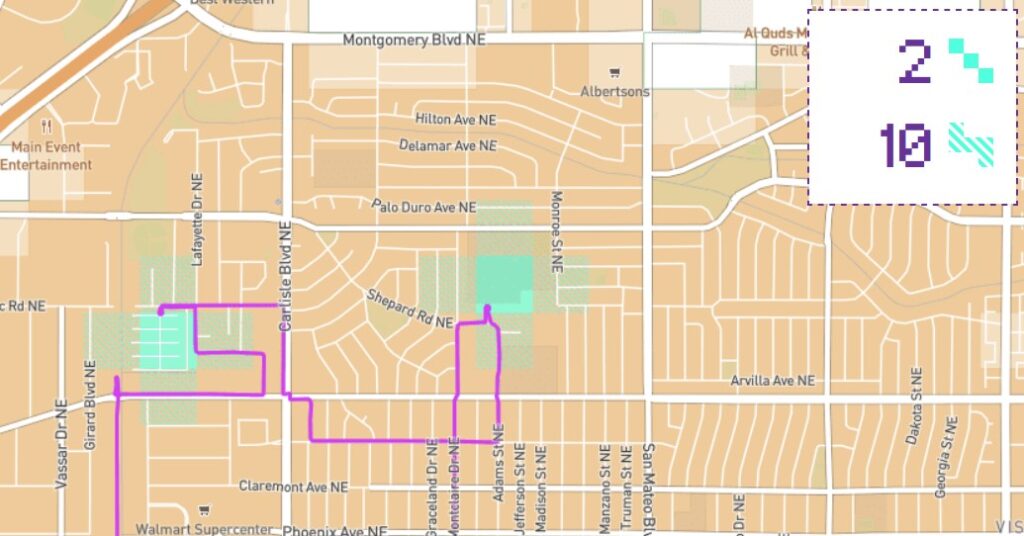

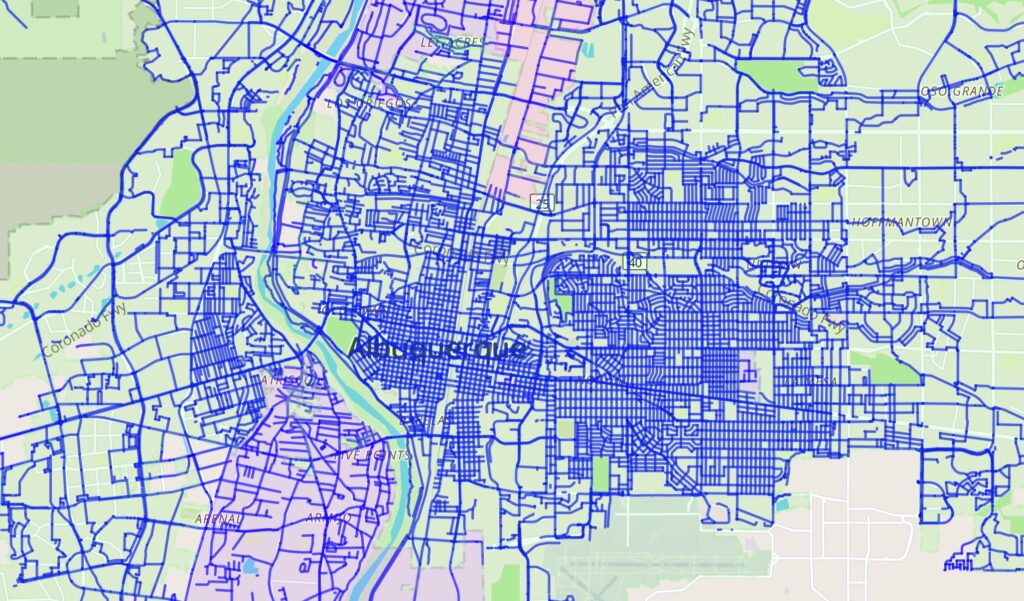

I rode down street after street today of affluent Los Ranchos homes colored pink on my version of Annalise’s maps – horse pastures, hayfields, one in sunflowers, all getting the tax break. This is not commercial agriculture, or “subsistence farming”, as one court ruling suggested was the intention of the 1967 state statute. These are hobby farms.

We have a set of rules – a state statute, implemented by our local county government, that is providing a financial incentive for this use of water, which Annalise estimates at ~10,000 acre feet per year in Bernalillo County.

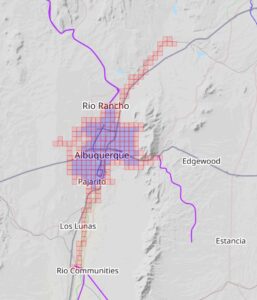

Ribbons of Green

The title of the proto-book is Ribbons of Green, after a line in John Van Dyke’s oddly dishonest masterpiece The Desert. In our work, Bob and I are playing with a theme – that we make progress by thinking of “the river” as more than the narrow strip that flows between the levees. Our notion of the river includes the water we move out across the valley floor – the ditches, the shallow aquifers from which we pump to water valley yards, a culturally and biologically rich and complex system lain across a valley floor where an unencumbered river once spread spring floodwaters on its own.

It is interesting to think about what the ribbons will look like five years from now, or ten. Between the levees, in the river’s main channel, the die seems cast – we’ve apparently decided as a community that we’re fine with letting it dry. Maybe Texas will have a say in what comes next – sooner or later our Rio Grande Compact obligation to get water downstream to Texas will require us to put more water into the river channel, perhaps reducing the Los Ranchos blanket of green in the process. Or reducing the green somewhere. Riverside bosque? Farms?

Perhaps the struggle to help the dwindling Rio Grande silvery minnow, our Endangered Species icon, will lead to more water in the river and less in Los Ranchos (or less somewhere).

On my book research bike rides (such a racket!), I have come to stop random ditch walkers and yard waterers and engage them in idle conversation. In general, they love the green, have little idea where the water is coming from, and are delighted with the current situation.

The Compact or the Endangered Species Act as drivers may ultimately change things, but they are something different from our community values. As seen in the Water Management Design Principles above, we seem fine with spreading the green outside across the valley floor while letting the part of the river between the levees, its main channel, go dry.

If it were otherwise, we’d have different rules.