Tag team.

There was a playful glee, like he knew he was getting away with something, something frowned upon yet worth doing, with Richard Parker’s “development days.”

Richard and I were youngsters, 30-something kids who had been handed the keys to a metaphorical roadster, and we wanted to see how fast it would go. I looked up to him as an experienced elder, though I realize in reading his obituary this morning that he was four years younger than I.

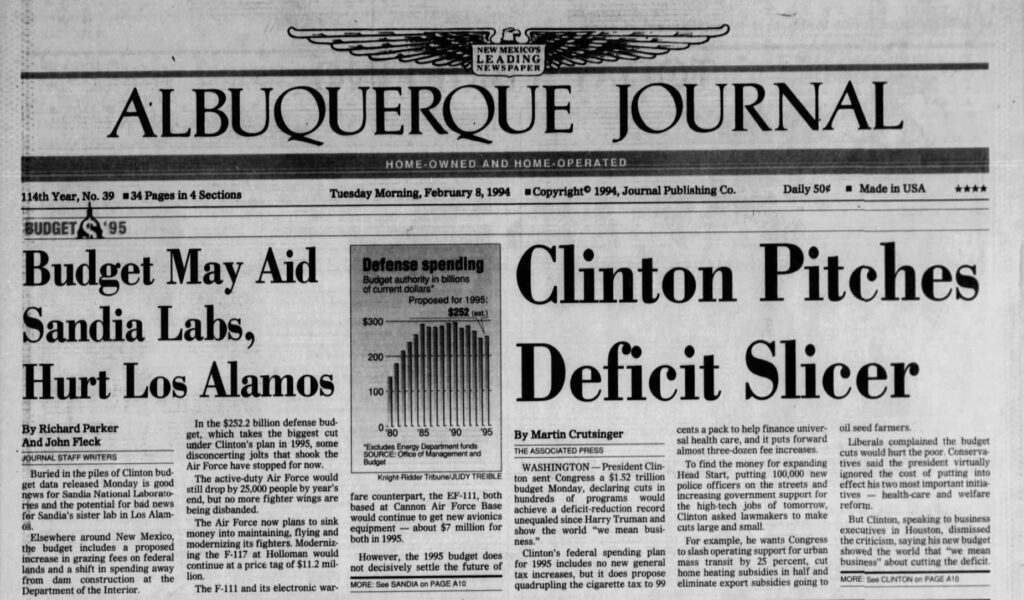

He was in D.C., the Albuquerque Journal’s Washington correspondent, when I was learning the craft of journalism three decades ago on the Albuquerque side of what amounted to a shared beat covering the cauldron of federal defense policy. New Mexico is a military-industrial colony, and the flow of federal funding to design and maintain nuclear weapons, to fly jets and sometimes drop bombs, to clean up Cold War environmental messes, was a fiercely challenging journalistic training ground.

When I would visit D.C. (those were the days of newsroom travel budgets), Richard would take me to bars with ridiculously expensive cocktails. I don’t drink.

The metaphorical roadster was the big printing presses in the back, and a distribution system that involved people staying up all night printing up whatever we had to say and then driving around town throwing it on a hundred thousand driveways. A hundred thousand driveways! Senators and their staffers read every word we wrote. Senators!

The mentoring – did it work that way, was Richard mentoring me? – involved the impish confidence with which Richard would seize a story. I watched and modeled, learned that our job was to decide what the story was and let our editors know, not wait for them. We needed to drive the roadster, but (and here the metaphor breaks down) make our bosses think that they were at the wheel.

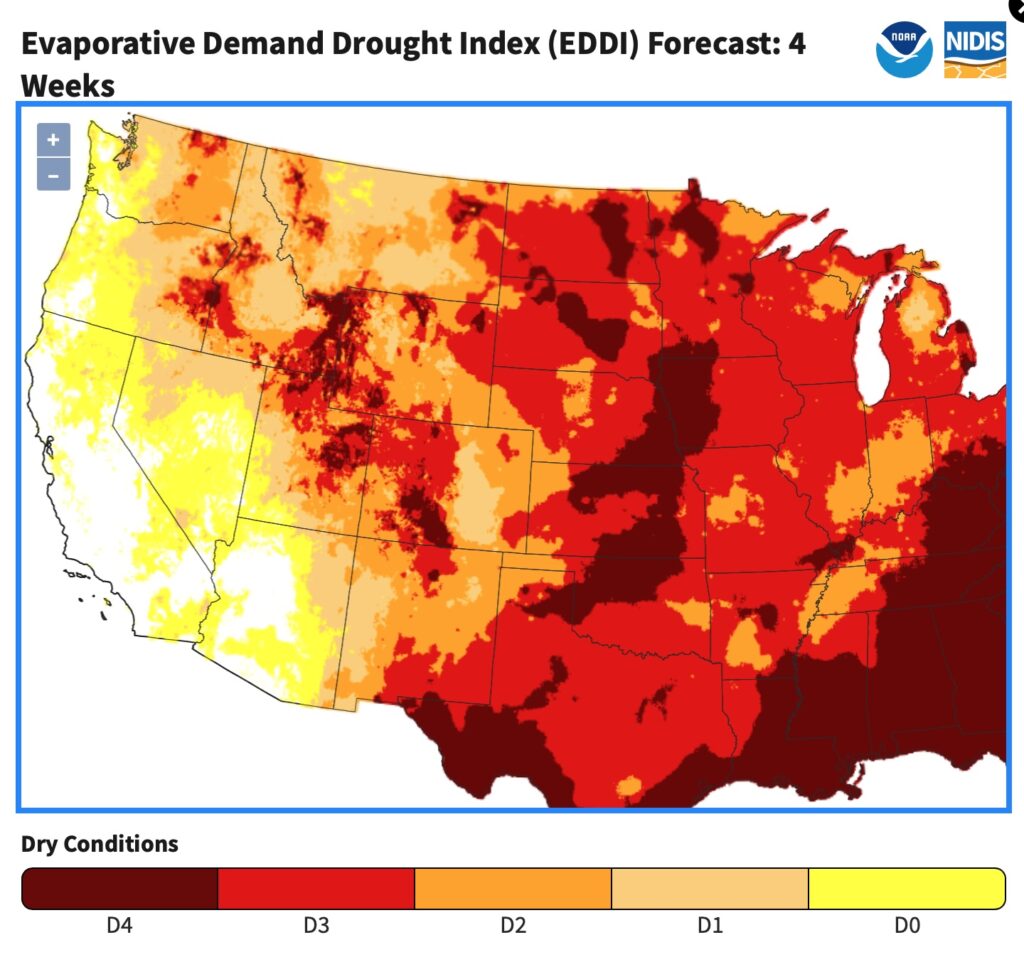

I loved federal budget release day with Richard, the rush of a pile of new documents with tables of data and an obligation to our community to help make sense of it all – “disconcerting jolts that shook the Air Force have stopped for now,” “a shift in spending away from dam construction at the Department of the Interior.” It was a dance, a lovely dance.

“Development days” were Richard’s way of blowing it all off to think about stuff. Or maybe he was just going to the National Gallery to see the Matisse cutouts, I dunno. He was half a continent away, it was the time before mobile phones, it was hard to keep track of him, which he used to full advantage.

The Crossing

Richard Parker

Richard had long since left D.C. and returned to his beloved borderlands. We’ve stayed in sporadic touch in the decades since, but we didn’t remain close. I’m lousy at that.

Last fall Richard sent me the pdf of the page proofs of his new book The Crossing: El Paso, the Southwest, and America’s Forgotten Origin Story, but a pdf is no way to read an old friend’s book, so I’ve been waiting for my copy of the book.

The El Paso Matters obituary (thanks, Diego) makes clear Richard knew he was dying, but he made it to Literarity, an El Paso bookstore, to sign copies of the book.

I look forward to reading it.