One of the guys at the Las Vegas Marina yesterday was sounding optimistic. Sure, the lake level’s low, he said, but they expect it to start rising soon. Plus, he said he heard they expect it to eventually come up another 60 feet. He shrugged as if to say, “Dunno, but that’s what I heard,” as if he didn’t quite believe it himself.

For the record, the latest Bureau of Reclamation projection has Mead dropping another 6 feet in the next year. We haven’t even started the winter snow season, so it’s too early to do anything other than shrug at the projection, but that’s what it says.

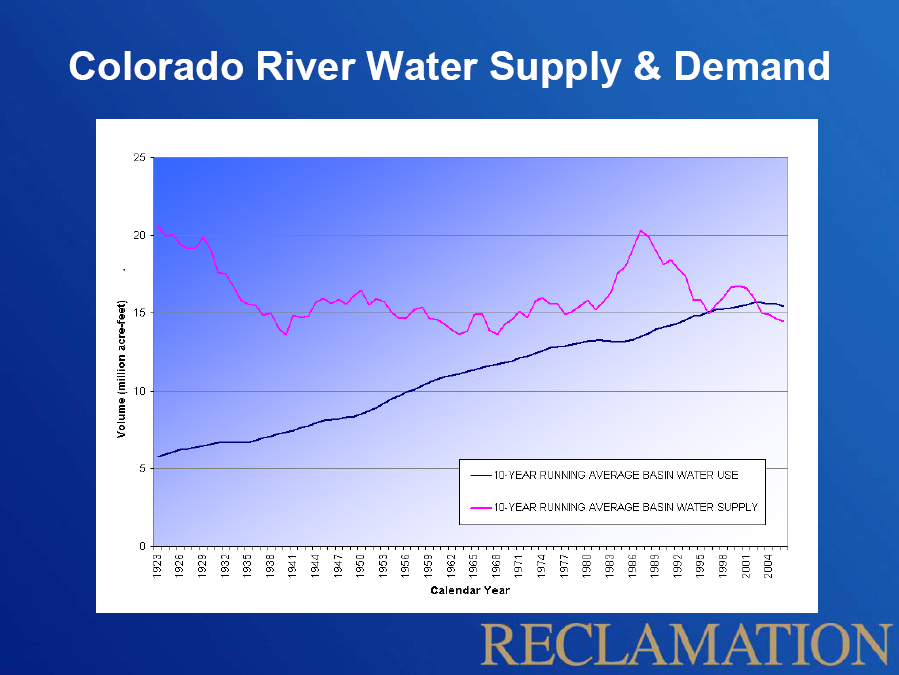

The reason, of course, is that for the last decade, demand for water on the Colorado River has exceeded supply. This is a telling graphic that’s been making the rounds this year as we all watched Lake Mead slip toward its current historic low. (Click the image for a bigger version.)

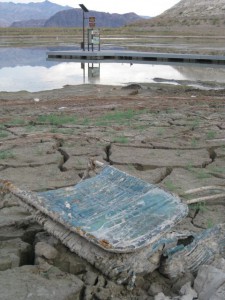

Another way of looking at the situation is out at the end of what used to be the boat ramp at Boulder Harbor, another of the former boating sites on the western edge of Lake Mead. I stopped by this afternoon on my continuing tour of places the lake used to be.

The boat ramp’s closed. What’s left of the harbor can’t be more than a few feet deep at this point. There were literally hundreds of coots poking around in the muck, and I watched an osprey fish (successfully). The strangest bird was a white domestic goose, who squawked loudly when I got too close, but couldn’t be bothered to actually flee. The coots did flee, but in a lackadaisical way that suggested they were not all that concerned that I would eat them.

The narrow inlet to the harbor is nearly dried up, and with a few more feet of lake level drop, Boulder Harbor will dry up completely.

If the guy I talked to yesterday at the marina is right, of course, Boulder Harbor will rise again, and the power boats will return. Sixty feet would be sweet indeed.