One of my Twitter friends (I wish I could remember who to share credit) pointed out how much this photo, taken last month by an unnamed member of the International Space Station crew, tells us about rivers and human society:

The View of Mead From Upstream

Folks on the Colorado River upstream of Lake Mead are sounding a little nervous.

Dennis Webb had a very nice piece in the Grand Junction Sentinel over the weekend taking stock. Meet Colorado rancher Carlyle Currier:

When he hears that Lake Mead’s water level is at a historic low, he worries about the degree to which Powell may be relied on to stabilize Mead’s water supply.

That Lake Powell supply is water that Colorado and other states in the upper basin of that Colorado River scarcely can afford to let go, Currier said.

Currier and others involved in water policy in western Colorado see Lake Powell as a bank account for upper basin states, ensuring their ability to fulfill their water delivery obligation to lower basin states under the terms of the 1922 Colorado River Compact.

Lower basin states are using more Colorado River water than they are entitled to under the compact — a rate that has proven to be an unsustainable during a decade of drought and has drawn down Lake Mead.

“If we are required to allow too much water to meet the needs of the lower basin … and those that benefit from Lake Mead, well, that puts us in jeopardy of lowering Lake Powell too much and getting us in real trouble if we do have another severe drought like 2002,” Currier said.

It’s not a far-fetched fear. Recall the folks I talked to at Lake Mead last month, who argued that the solution to their lake’s problems was to release more water from Lake Powell upstream. While the current legal structure makes that difficult beyond efforts to equalize the contents of the two reservoirs so that they can, in theory, share both surplus and shortage, it’s a common line of argument.

Current contents:

- Lake Powell: 15.2 million acre feet

- Lake Mead: 10.0 maf

Stuff I Wrote Elsewhere: The “Festering Issue” of NM Domestic Wells

From the morning paper, a quick look at the New Mexico Court of Appeals decision on the state’s domestic well statute (sub/ad req):

New Mexico’s law giving homeowners the right to drill their own water well is legal and does not unfairly harm other water users in violation of the state constitution, according to the New Mexico Court of Appeals.

The court, in a decision issued late Friday, overruled a lower court decision that the domestic well law violated the state constitution because of harm such well drilling could have on nearby water rights holders.

The Appeals Court ruled that the state engineer, the state’s top water official, has sufficient administrative authority to manage water resources in such a way that pre-existing water rights are protected.

But this really deserves more than a quick look, because there’s a nuance in the decision that telegraphs what might be happening next:

The Appeals Court ruled that the Legislature created the statute requiring the state engineer to issue domestic well permits, and that it is therefore up to the state engineer and the Legislature to fix any resulting problems in the administration of water rights.

“The present case is a showcase of the festering issues involving senior water rights owners, the Legislature, and the State Engineer,” the court ruling said. (emphasis added)

In other words, appeal or not, we haven’t heard the last of this.

Stuff I Wrote Elsewhere: NM Water Rights Ruling

My education in economics included a lot of discussion of the importance of clarity in property rights regimes. You’ve got to know who owns what.

New Mexico water law in this regard is a tangled mess. In large areas of the state, we lack formal adjudication of water rights. We do know some things about who is entitled to use how much water, but the very important question of the priority of those rights – who is first in the water use pecking order when there is a shortage – is undetermined.

I had a story in this morning’s paper (sub/ad req) about an important NM Appeals Court decision that frankly does little to clarify the situation, other than throwing out what some had hoped would provide a short cut to resolving the uncertainty. Turns out the short cut was illegal:

The ruling throws the water rights problem, which has left a shadow of uncertainty about allocating the scarce resource in arid New Mexico, back into the hands of the state Legislature.

It can take decades for courts to sort out water rights entitlements in New Mexico river basins. During serious drought, the problem is that in many parts of the state, there is no mechanism for determining who is entitled to water and whose use will be curtailed.

That problem is particularly acute on the stretch of the Rio Grande between Cochiti Dam and Socorro, where farm communities and the Albuquerque metro area have an uneasy coexistence when it comes to water.

“In the middle Rio Grande, you have huge uncertainty,” said Peter White, a Santa Fe water lawyer who was not involved in the case.

Who Needs to Understand Drought?

Ed Polasko had a great comment on one of my recent Lake Mead posts that I thought was worth elevating. I was riffing on the lack of public understanding, even in the face of Mead’s dropping levels, of the drought and water use problem facing the West. Ed’s response:

For the average Joe/Mary, drought will only matter when they turn on their bathroom faucet and no water comes out, or when the water bill quadruples (or increases ten fold). Everyone else who now “gets it” is a either a water manager, environmentally enlightened, or a climate wonk. That’s where we are and always will be.

It’s a great point. Until we reach thresholds like those Ed describes, there is not likely to be broad public awareness here in the affluent U.S. about these issues. And the whole point of policy response is to find ways to avoid those thresholds. So the conversation inevitably will be among those water wonks that Ed describes.

Energy and Water in the California Desert

Osha Gray Davidson, writing about yesterday’s Blythe Solar Power Project announcement, highlights a key issue:

[T]he project will now have a much smaller “water footprint” thanks to a decision to use air cooling, which consumes no water, at the cost of somewhat reduced efficiency.

Cynthia Barnett, a noted water expert and author, calls the Blythe plant “crucial.”

“It shows that the U.S. recognizes the link between water and energy,” she says. “Every form of energy is water intensive — not just solar. But Blythe is a good sign for the future. It shows we can generate renewable energy without over-using water.”

Powell and Watersheds in the 21st Century

John Wesley Powell, the 19th century explorer, scientist and visionary who first tried to map and explain the West’s water resources, famously argued that government jurisdictions should be established based on watershed boundaries.

He was ignored on this point (as he was on others). But I’ve been playing recently with an argument that elaborates on this theme – that we’ve in a sense expanded the boundaries in the West of what counts as a “watershed” enormously, at least in the context of way Powell was thinking of it – a geographically bounded space based on a common water supply.

Stockton water writer Alex Breitler noted the connections last week in a comment on dropping levels at Lake Mead.

Here in the West, that space now runs from the Colorado River Basin east, across the continental divide, to include the front range communities and places like Albuquerque supplied by inter-basin transfers. To the west, it reaches across the Imperial Valley farm district to Southern California, which is then interconnected via pumping from the Sacramento Delta to the major watersheds of Northern California.

Here’s Breitler, with a nice map to aid your thinking:

Here’s Breitler, with a nice map to aid your thinking:

Southern California water districts, including Metropolitan which serves LA and San Diego, rely on the Colorado River for a portion of their supply.

Notice the California Aqueduct, also feeding So Cal. That water is pumped out of the Delta near Tracy.

So… if Colorado River storage on Lake Mead dries up, well…

“That means they’ll want to pull more water out of the Delta,” San Joaquin County water resources coordinator Mel Lytle said at a meeting this week.

River Beat: The Investment Perspective

Investors need to take long term water supply risks into account as they think about municipal bonds, according to a new analysis by the environmental-investor group Ceres published this week:

The report shows that some of the nation’s largest public utilities may face moderate to severe water supply shortfalls in the coming years, yet these risks are not reflected in the pricing or disclosure of bonds that public utilities rely on to finance their infrastructure projects. There are about 50,000 public water utilities in this country serving an estimated 258 million Americans. The electric power sector is enormously water-intensive – it accounts for 41 percent of the nation’s freshwater withdrawals.

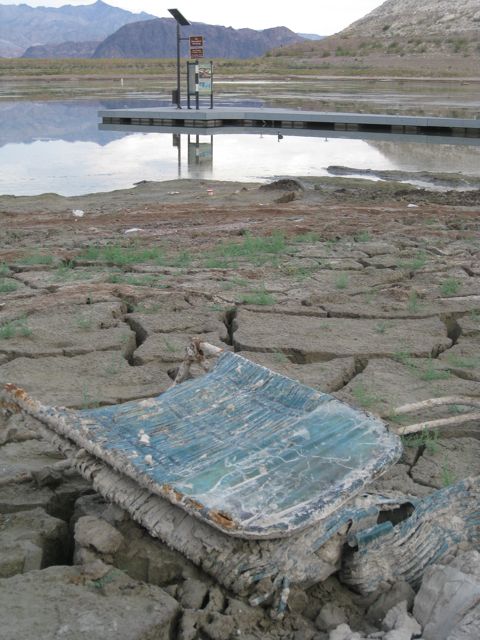

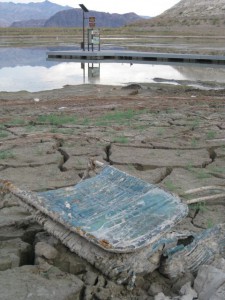

Lake Mead, October 2010

“Water scarcity is a growing risk to many public utilities across the country and investors owning utility bonds don’t even know it,” said Mindy Lubber, president of Ceres, which authored the report. “Utilities rely on water to repay their bond debts. If water supplies run short, utility revenues potentially fall, which means less money to pay off their bonds. Our report makes clear that this risk scenario is a distinct possibility for utilities in water-stressed regions and bond investors should be aware of it.”

The report comes as Lake Mead draws attention for dropping to historic low levels, and the first serious discussions are underway about a shortage declaration on the Colorado River. From the Ceres report, some examples of where the risk lies, including Los Angeles:

The Los Angeles Department of Water & Power’s water system bond received the highest risk score of all water utilities, based on tight restrictions on local water supplies due to environmental regulations and prolonged drought. The municipal system, the nation’s largest, is also highly reliant on vulnerable water imports, including the Colorado River. The utility’s water bond was rated “AA+” and “Aa2” by Fitch and Moody’s, respectively, earlier this year.

And the greater Phoenix area:

The Phoenix and Glendale, AZ utilities—systems with high reliance on increasingly expensive and potentially volatile out-of-state water imports from the Colorado River—also received high water risks scores.

The report also notes that the risk applies to the power sector, both because of dwindling hydro power from Hoover and other dams as water levels drop, and also because of the need for water to support new sources of power:

The Los Angeles electric power system‘s risks are driven in part by reductions in power generated at the Hoover Dam due to low water flows in the Colorado River Basin. The system may also see reduced power deliveries from one of its major coalfired power plants in Utah, due to heavy competition for dwindling cooling water flows.

(h/t Lisa Song)

Hoover Dam

Mom says I drew a picture of Hoover Dam when I was five and gave a “report” on it in kindergarten for “what I did on my Christmas vacation”. As mom tells the story, the teacher was impressed with the rigor and detail I offered. I was an exceptional child. At least that’s how mom tells it.

To be honest, the only thing I remember is a sense of foreboding. I remember the view from the Arizona side, driving down the switchbacks until we got to the overlook, getting out and looking down at the massive intake towers. In the winter of 1964-65, they had begun holding water upstream, behind the newly completed Glen Canyon Dam. So the levels were low, and it must have looked very much like it does in this picture, which I took last night. All I remember is the fact that, from a child’s vantage, point, that was scary frickin’ far down there! I don’t remember looking down into the spillway, but I must have.

And I remember the tour guide telling us that Hoover Dam has enough concrete in it to pave a road all the way from San Francisco to New York, or some such. So I guess my childish fear of the abyss somehow mixed with a sense of wonder.

The “San Francisco to New York” isn’t part of the tour schtick any more. At least it wasn’t when I took it last night. But the sense of wonder, the triumphalism of Hoover Dam, remains.

Stuff I Wrote Elsewhere: Meanwhile, Back on the Rio Grande

While I’ve been away, my friends back in Albuquerque were kind enough to print a bunch of copies of my ruminations on La Niña and the Rio Grande and throw them on people’s driveways this morning (sub/ad req):

[M]ore than La Niña is at work this year, according to Glen MacDonald, a climate researcher at the University of California Los Angeles.

Beyond La Niña, in the equatorial Pacific, researchers like MacDonald have been watching two other large-scale ocean patterns that also seen to have their own influences on North American droughts.

One is a long-term, persistent pattern of warmer water in the north Pacific. The second involves vast stretches of warm water in the north Atlantic. This year, they all seem to be lined up alongside La Niña, ganging up in a worst case scenario for drought in the Southwest, MacDonald told me.

When all three are in sync, according to MacDonald, “the propensity for drought indeed extends east from California right across your region to Texas.”

The most famous case of oceans in sync like this was during the heart of the drought of the 1950s — New Mexico’s worst in the last century.