By Eric Kuhn and John Fleck

When the Colorado River Compact Commission adjourned two days previously, on Nov. 20, 1922, two major Colorado River Compact issues had been left unresolved; the amount of water that would be apportioned to the Lower Basin and how the compact would address the need for storage to protect the Imperial Valley from flooding and stabilize river flows. The commission had also identified potential solutions to both.

The view from afar

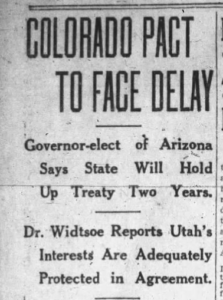

Salt Lake Tribune, Nov. 22, 1922

The view from outside the tense, cloistered negotiations being held at Bishop’s Lodge outside Santa Fe remained optimistic. In a widely publicized telegram to President Warren G. Harding, Commission Chairman Herbert Hoover (who was then Harding’s Secretary of Commerce) described the unprecedented nature of the nearly completed task:

It is worthy of note that this is the first occasion when more than two states have come together under the direct provisions of the constitution established through this method the solution of interstate difficulties outside the courts.

But in a blunt case of dueling public telegrams, Arizona’s Governor-elect, George W. Hunt, warned that getting seven state buy in remained an uphill slog. Arizona, he wrote, would not sign onto a compact until its rights to water, and infrastructure, to meet the state’s ambitious irrigation plans were clarified.

Even as the negotiators closed in on a deal at Bishop’s Lodge, Hunt’s increasingly strident rhetoric made clear that what came after the negotiations would not be easy.

The Lower Basin’s extra million acre feet confirmed

The commissioners and their advisors had spent a busy Tuesday caucusing and having individual discussions about closing the deal and agreeing to a compact. They made considerable progress.

Hoover opened the 22nd meeting with a discussion of Article III, the apportionment of the use of water between the two basins. Arizona’s Winfield Norviel had tentatively agreed to compromise alternative #4 from the solution list that Nevada’s James Scrugham had suggested. The Lower Basin would be given the rights to increase its uses by an additional one million acre-feet per year making its total apportionment 8.5 million acre-feet.

Hoover then took the commission through seven subparagraphs of Article III. In addition to a new Article III(b) providing the Lower Basin with the additional million acre-feet, the drafting committee had decided to change the language of Article III(a), instead of limiting appropriations, the compact would be apportioning beneficial consumptive use between the two basins. Hoover noted that because they couldn’t agree on a common definition of the word, they had decided to avoid using the term “appropriation” in the compact. Wyoming’s Frank Emerson had raised another concern, he wanted the compact written so that the common person could understand it.

Article III(a) apportions in perpetuity to each basin “for its exclusive use, 7,500,000 acre-feet per annum, which shall include all water necessary for the supply of any rights which may now exist.” Norviel asked why the division is being made between the two basins, not the two divisions. Hoover responded, “the division we confine purely to a political division and the basin to a physical division.” Hoover then read Article III(b), “The lower basin is given the right to increase its beneficial consumptive use by the further quantity of one million acre-feet per annum.” The commissioners suggested several potential wording changes, but decided to agree to it for the moment, then come back to it for further wordsmithing.

Water for Mexico and the expectation of “surplus”

Moving on Hoover noted that the provision dealing with water for Mexico had been moved from a separate article (IV) to Article III(c), but the concept was the same. Water for Mexico would first come from the surplus. If the surplus was insufficient, then the deficiency would be equally borne between the two basins and the States of the Upper Division would deliver one half of deficiency at Lee Ferry in addition to that provided in paragraph III(d). Again, individual commissioners made suggestions for wording changes, but the commission agreed to the paragraph in concept.

Article III(d) remained basically unchanged from previous drafts; the States of the Upper Division would not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75 million acre feet every ten years nor below a flow of four million acre-feet annually. At this point in drafting, the commission assumed that the water accounting year would run from July 1st to June 30th.

They then moved to Article III(e), which prohibited the States of the Upper Division from withholding and the States of the Lower Division from requiring the “delivery of water which cannot reasonably be applied to beneficial, agricultural, and domestic uses.” James Srcugham raised the question of how this applied to mining, milling, and such uses. Hoover suggested they deal with that in the definition of “domestic”

The remaining discussion focused on Articles III(f) and (g), the provisions setting out the details for the future apportionment of the surplus pool. While several commissioners were confused by the initial wording, the concept was that under III(f) a further apportionment could be made of the water unapportioned by paragraphs III (a), (b), and (c) after July 1st, 1968, and when either basin had reached the total beneficial consumptive use set out in III(a) and (b). Paragraph III(g) provided that any two states or one state and the president of the United States could give notice to the other states to trigger the next apportionment round. The next agreement would also be subject to ratification by the legislatures of each state and Congress.

There was general agreement except for the date when the new apportionment round could be triggered. Arizona’s Norviel wanted a shorter period, no more than 30 years. The upper river commissioners wanted a longer period. They would end up compromising on a 40-year period.

Authors note: today given the reality that the flow of the river is much smaller than what was assumed in 1922, these two articles are almost never discussed, but to the commissioners that negotiated the compact in 1922 they were essential to the political compromises necessary for unanimous agreement on the compact, illustrating how important the overestimate of the river’s flow, discussed in our book Science Be Dammed, was to the negotiators’ ability to come to agreement.

Whither storage

With the caveat that more drafting was needed, Commission had reached agreement on Article III, a major accomplishment. The question of how deal with storage remained unsettled. Hoover planned to address this issue in the next meeting, their 23rd, scheduled for that afternoon. In the remaining morning session, Hoover turned to the issue of navigation and a provision proposed by his federal legal advisor, Attomar Hamele.

There was agreement in the room that the Colorado River was no longer navigable, and navigation should not interfere with other beneficial uses. But what if Congress did not agree? In fact, both Hoover and Hamele were predicting that many in Congress would not agree. Hoover’s solution was to suggest that if Congress did not agree, the remaining provisions of the compact would remain, and the pact would not have to be renegotiated. James Scrugham suggests a committee to draft such language.

Hamele suggested a compact provision that protects the rights of the United States. He pointed out that project works built and funded by the United States were the largest source of irrigation water in the basin and many more were being planned and that these projects needed full protection. If he had stopped there, he may have succeeded, but he went on to tell the commissioners that the United States also had a claim to the unnapropriated waters in the basin. To that, all eight commissioners objected. After a difficult discussion, Hoover concluded “an expression reserving the unappropriated waters destroys the entire basis and sense and purpose of this whole commission.” Nevada’s Srugham added that with such a provision none of the seven states would ratify the compact. The discussion ended.

After a long break, Hoover convened the 23rd meeting at 3:45 PM. He immediately turned to the new Article VIII which he hoped would address the Californians need for a storage provision. After the meeting Hoover and McClure had convened with the Californians most had left Santa Fe angry and disgusted. Hoover, recognizing his mistake, convinced J. S. Nickerson, President of the Board of the Imperial Irrigation District to stay and assist McClure.

After a discussion and wordsmithing of the drafting committee’s proposal, Hoover read the proposed article VIII; “Present perfected rights to the beneficial use of the waters of the Colorado River System shall constitute the first charge upon the water hereby apportioned to that division of the basin in which they are situated. All uses which may be perfected subsequent to the effective date of this compact shall be satisfied exclusively from the remaining water apportioned to that division of the basin in which they are situate and shall have no claim upon any part of the water apportioned to the other division of the basin. Whenever works of capacity sufficient to store 5,000,000 acre-feet of water have been constructed on the Colorado River within or for the benefit of the lower basin, any rights which the users of water in the lower basin may have against the users of water in the upper basin shall be satisfied thereafter from the waters so stored.” The drafting committee had also proposed adding the remedies language to the end of paragraph VIII (combining paragraphs VIII and IX).

The commissioners, except New Mexico’s Steven Davis, were OK in concept, but thought the language was very confusing. The Commission would end up discussing numerous drafts before the article was finalized. Steven Davis, although appointed by Hoover to help with the drafting, was now an unwilling participant. He told the others he strenuously objected to the third sentence of the paragraph. Davis, a New Mexico Supreme Court Justice, found the legal logic flawed. If the concept was that perfected rights that existed before the compact could not be impacted by the compact, how could that same compact limit them by requiring that they be satisfied by future stored water? Davis added that he would not, however, vote against the article and interfere with the unanimous approval of the compact. Carpenter preferred the storage trigger be 1,000,000 not 5,000,000 acre-feet but understood the lower river would not go that low.

A 4 million acre foot flow minimum?

Recognizing that Article VIII needed more work, they went onto other matters including a broad discussion of article I, the purposes of the compact. Before they adjourned, Hoover raised the question of the four million acre-feet annual minimum annual flow under Article III(d). Now with Articles III(e) and VIII, was it still needed? Winfield Norviel responded that he was still in favor of it. Hoover then adjourned the meeting until Thursday at 9:30 AM, but requested the drafting committee continue their work in an evening session.