A month of warm, dry weather left Lakes Mead and Powell with 24.8 million acre feet of water at the end of November, 169,000 acre feet less than had been forecast a month earlier.

The crux of the Colorado River Compact lies in Article III (d):

The States of the Upper Division will not cause the flow of the river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75,000,000 acre-feet for any period of ten consecutive years reckoned in continuing progressive series beginning with the first day of October next succeeding the ratification of this compact.

With Glen Canyon Dam to regulate flow, that translates to 7.5 million acre feet per year delivered past Lee’s Ferry from Upper to Lower Basin. Add in the Upper Basin’s share of water for Mexico, and you have an average annual release of 8.23maf.

If things are “good” (a relative term in the arid western United States), there might be a little bit of extra water, which looks like it might be the case this year. The complex of reservoir operating rules call for “balancing”, using a Byzantine set of formulas. This year, the rules suggest a likely release of 9 million acre feet – an extra 730,000 acre feet above and beyond the Lower Basin’s Compact-guaranteed share.

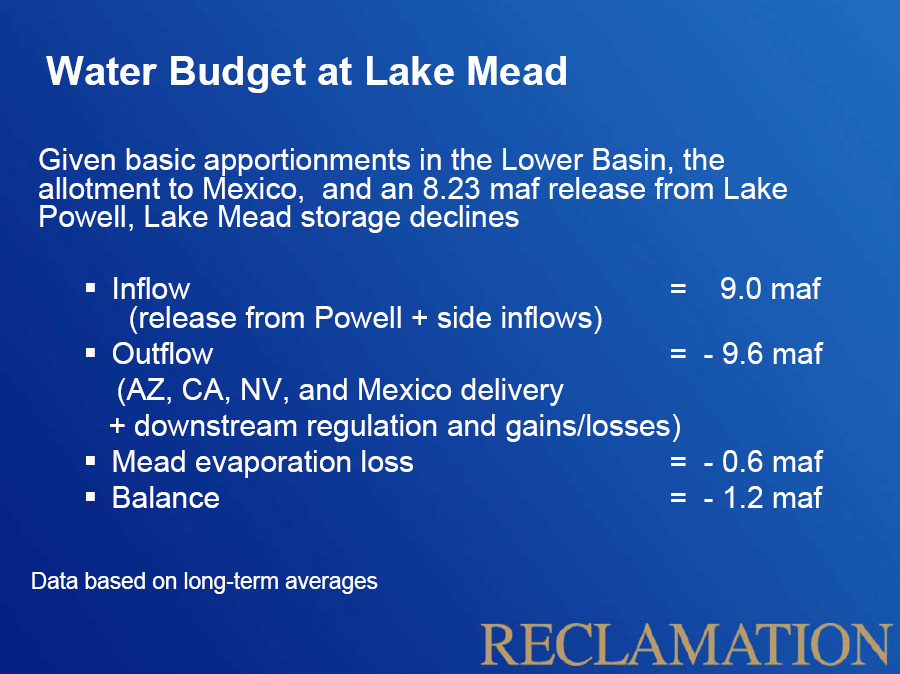

And yet if you look at the latest “24-month study”, the monthly Bureau of Reclamation reservoir operating forecast, you’ll see that Lake Mead, despite getting a shot of bonus water, is forecast to drop another 7 feet in elevation in the 2010-11 water year.

Here is a reminder of why:

Unless the Upper Basin states deliver additional water above and beyond that guaranteed under the Colorado River Compact, Lake Mead will keep declining unless and until Lower Basin states reduce their consumption.

With numbers like that, 60,000 acre feet seems chump change. That’s the shortfall in Lake Powell at the end of November, with reservoir levels 6 inches below the month-ago forecast:

The November 24-Month Study projected that Lake Powell would end November at an elevation of 3630.85 feet above sea level. The elevation of Lake Powell at the end of the day on November 30, 2010 was 3630.31 feet above sea level. This 0.54 foot difference is equivalent to about 60,000 acre-feet of storage in Lake Powell.

Lake Mead ended the month with a surface elevation of 1081.94, down from a month-ago forecast of 1083.25. That translates to 109,000 acre feet less water.

References:

That’s snow pack as of Friday in the Upper Colorado River Basin. Those of us down in New Mexico, dependent on the San Juan and Rio Grande, are sucking wind, as you can see. But much of the basin looks dandy! (And a huge thanks to DG. I’m always looking for good at-a-glance graphics for tracking snow pack. Consider that one bookmarked and shared.)

That’s snow pack as of Friday in the Upper Colorado River Basin. Those of us down in New Mexico, dependent on the San Juan and Rio Grande, are sucking wind, as you can see. But much of the basin looks dandy! (And a huge thanks to DG. I’m always looking for good at-a-glance graphics for tracking snow pack. Consider that one bookmarked and shared.)