From Thursday’s newspaper (sub/ad req), a look at what is increasingly looking to be a very dry year on the Rio Grande, which has become entangled in a Byzantine governance issue involving allocation and distribution of Lower Rio Grande water:

In recent years, dry conditions have made managing the river more difficult. Eight out of the past 10 years have seen below-average flows at the Otowi river gauging station between Santa Fe and Los Alamos.

Sharing water south of Elephant Butte, among farmers in southern New Mexico and Texas, was a major topic of discussion at Wednesday’s meeting.

Because of a new agreement between El Paso and Las Cruces-area irrigators for division of Rio Grande water, most of this year’s water coming out of Elephant Butte reservoir is flowing past New Mexico farmers for use in Texas.

New Mexico irrigators agreed to the deal in an effort to head off interstate litigation with Texas in a dispute over the effects of New Mexico groundwater pumping on Rio Grande flows.

State officials object to the deal. D’Antonio told members of the Compact Commission on Wednesday the agreement, which has resulted in an increase of water going to Texas farmers while New Mexico farmers’ share decreases, was “demonstrably lopsided and not sustainable.”

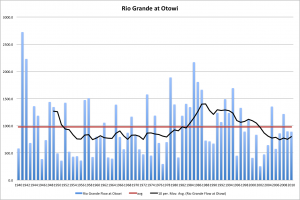

Rio Grande at Otowi source: New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission

The latest numbers from the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission show how remarkably dry the ’00’s have been. This is what’s called the “Otowi Index Flow”, which is the natural flow past the Otowi gauge in north-central New Mexico, as used for calculating Rio Grande Compact accounting. (It doesn’t count water added to the system from the Colorado Basin via the San Juan-Chama project. It’s also not a true “natural flow” estimate, because it doesn’t make any effort to adjust for water removed for irrigation upstream, in Colorado and Northern New Mexico. So not perfect, but the best we’ve got. Click on it to see it larger.)

A couple of key points here. First, note that the sustained drought of the 1950s is worse than what we’ve seen so for in the ’00’s. But also note that a lot of New Mexico’s population growth occurred subsequent to the 1950s drought, during a period that was unusually wet. Fourteen of the years in the 1980s and ’90s were wetter than the long term average.

During that time, New Mexico’s population grew by 40 percent. Including me.