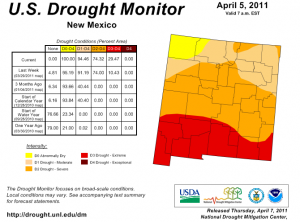

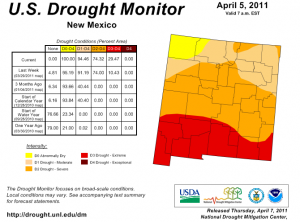

NM Drought Monitor

I’ve been spending a lot of my work days of late in a blow-by-blow rundown of the growing drought conditions in New Mexico:

An already dismal forecast for spring runoff in New Mexico’s rivers has gotten worse, after a dry, windy March sapped the state’s snowpack.

Spring and summer flow on the Rio Grande into Elephant Butte, the river’s largest water storage reservoir, is forecast to be just 33 percent of normal this year, federal forecasters said Wednesday afternoon. That is down from a forecast of 52 percent one month ago.

The steep decline came after a March that combined a near complete lack of precipitation with warm, dry winds that blew away some of the snow before it had a chance to melt, said Ed Polasko at the National Weather Service’s Albuquerque office.

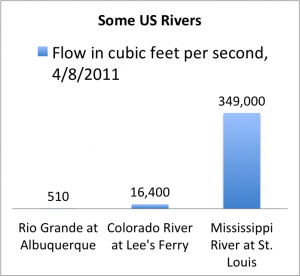

They’re working hard down south to dig a pilot channel simply to make sure the Rio Grande can reach Elephant Butte Reservoir – it has a tendency to plug itself up down there. We’ll get a better idea of the detailed flow forecast next week when the Bureau of Reclamation releases its Rio Grande operating plan, but it’s looking like the river through Albuquerque may only get up to 2,000 cubic feet per second during this year’s runoff peak.

Bosque overbanking, June 2005

That’s not much water.

I was reminded of that this morning, going through some old photos of the river in 2005. Our “bosque”, the ribbon of riparian woodlands that flanks the middle Rio Grande through north-central New Mexico, is a lovely place, but it’s an ecosystem on the edge. In its more natural state, before we built dams to store water for human use and to prevent flooding, along with levees and other engineered structures to channelize the water and move it efficiently toward downstream rivers, the Rio Grande would hop its banks in a good spring runoff and wander the valley floor. The result would have been a rich, meandering riparian ecosystem, with clumps of trees and grassy meadows and meandering patches of wetlands.

Most of the cottonwoods you see there now, I’m told, date to the last big flood, back in 1941, which seeded a big cohort of cottonwoods.

This picture was taken during 2005, when a big snowpack gave us a runoff peak north of 6,000 cfs in June. The 6,000-7,000 cfs level is pretty much the limit because of the built environment, especially a railroad bridge south of Socorro at San Marcial. (The Army Corps of Engineers uses the big flood control dam at Cochiti to cut manage the flow peak.) It takes more than that to get water up out of the river channel and back into the woods along much of the river, but there are places where the channel is shallow enough that you get scenes like this, and it’s delightful.

This year, not so much.

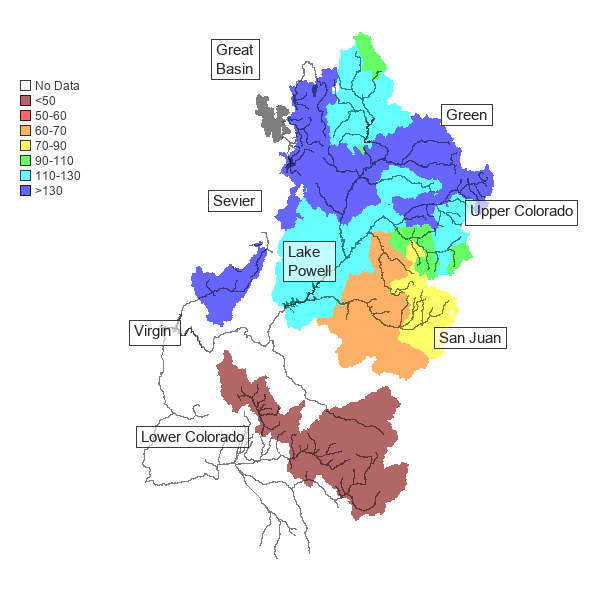

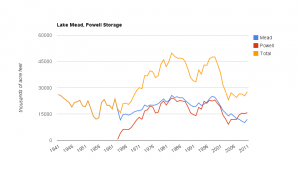

I’ve a chance to get out to California later this year and do some reporting on water issues, so I’ve been doing some reading, trying to get a better feel for where to focus my attention. This is in part driven by my belief that the West’s water issues have become inextricably linked, and to understand problems here in New Mexico I have to better understand the bigger picture.

I’ve a chance to get out to California later this year and do some reporting on water issues, so I’ve been doing some reading, trying to get a better feel for where to focus my attention. This is in part driven by my belief that the West’s water issues have become inextricably linked, and to understand problems here in New Mexico I have to better understand the bigger picture.