I’ve triggered some puzzlement among California water folks as I call around trying to understand the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta in preparation for my trip out there next month. Why does a New Mexican care? Other than the fact that it’s fascinating, of course. I mean what water wonk wouldn’t be fascinated by California’s water problems. But beyond entertainment value, but what’s the connection?

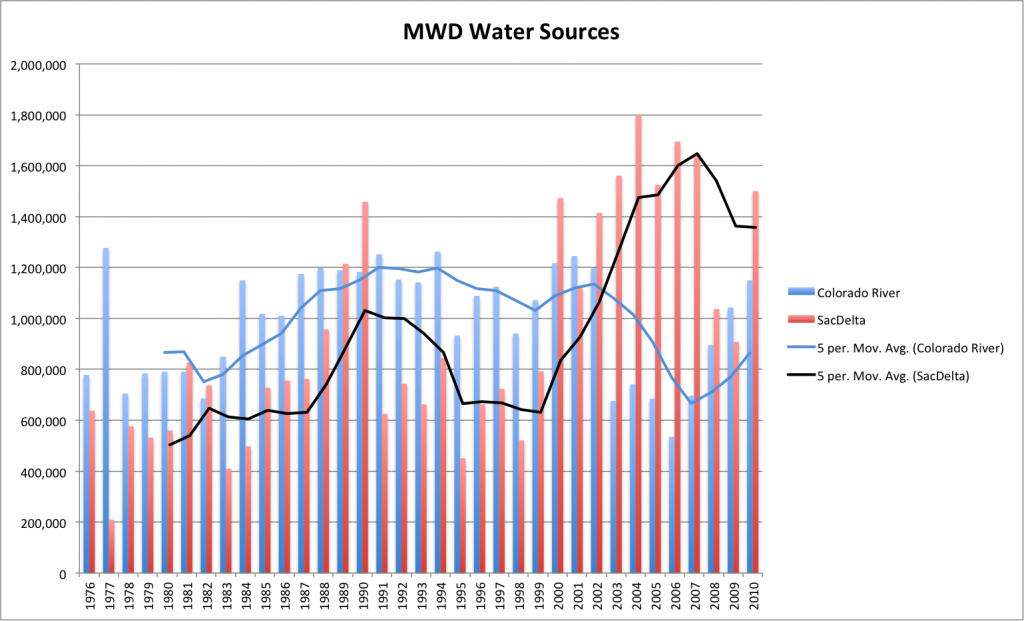

This graph (click to embiggen it) should help answer the question. It’s the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California’s water imports from the Colorado River and from the State Water Project’s Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta pumps. It shows a significant shift in southern California’s water sources beginning in 2000.

Why?

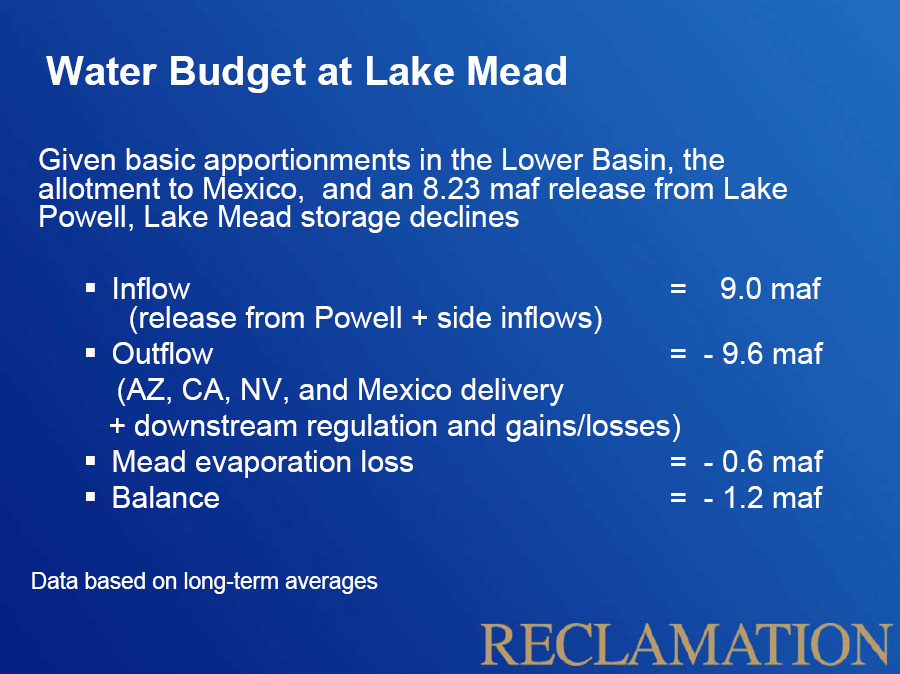

The answer lies in what folks in Colorado River management call “the 4.4 plan”. Under the Colorado River Compact and related laws and court decisions, California is legally entitled to 4.4 million acre feet of Colorado River water per year.

But for years, there was enough extra sloshing around the system that California was able (legally) to take more. Here’s Bennett Raley, Assistant Secretary of the Interior, explaining the situation during a 2002 congressional hearing:

The State of California has for decades received water in excess of the baseline quantity of 4.4 million acre-feet available to it in a normal, non-surplus year. The 4.4 million acre-feet of water available to California in a normal year is sufficient to meet the needs of agricultural interests such as the Palo Verde Irrigation District (PVID), the Yuma Project, the Imperial Irrigation District (IID) and the Coachella Valley Water District (CVWD) each year, and still fill a good portion of the Colorado River Aqueduct which helps to fuel the economy of coastal California.

The remainder of the Colorado River Aqueduct has been filled in past years with additional water not used by the States of Nevada and Arizona or water made available in years of surplus. Neither the historical fact of the repeated, and lawful, release to California of water not taken by Nevada or Arizona, nor the present reality of the dependency of California on this additional water, can alter the terms of the Decree. California has no legal right to the continued use of water in excess of 4.4 million acre-feet in a normal year. Nor does California=s use of additional water during times of surplus alter the immutable laws of nature. The Colorado River will have periods of surplus, periods of normal flow and periods of drought.

As the Central Arizona Project fully came on line, California had to bring its usage down to reflect that reality. One thing that happened is that the Metropolitan Water District’s use of Colorado River water went down, and its use of State Water Project water, pumped from the delta, went up, as the graph above shows.

And as Mike Taugher reminded us last week:

An increase in Delta pumping during the 2000s coincided with the collapse of several fish species….

Albuquerque began drinking Colorado River water two years ago. Santa Fe began drinking Colorado River water this year. We’ve joined hands with y’all out in California. And the cascading effects from our big river basin to yours shown in that graph are reminder of how our water infrastructure (both physical and institutional) is increasingly interconnected across much of the West. As are our problems.

As Pat Mulroy likes to say, we’ve created “the largest artificial watershed in the world.”